Actually, the sight of the Taj Mahal did not disappoint me. Steve and I set the alarm for 5:15 am, threw on some clothes, and slipped out of the Muslim home in which we were staying. We hurried down the dark street outside, where the temperature was almost chilly. Twenty minutes later, we stood at the Western gate of one of the most famous tourist attractions in the world.

Everyone knows what it looks like, right? I’d seen countless photographs. So why is it that walking through the archway into the huge grounds that contain it made my eyes widen; flooded me with a surge of pleasure? The proportions of the lawns, the trees, the walkways, the four minarets, that swollen white dome — the way they relate together —feels so right. The famous white structure is massive, yet the recessed archways and delicate marble latticework that were cut into every side give this great landmark a soul-stirring beauty. It’s pretty from every angle…

It’s pretty from every angle… And pretty up close.

And pretty up close. I’d had to guess how many selfies are taken there. Weird posing is also super popular.

I’d had to guess how many selfies are taken there. Weird posing is also super popular.

Steve and I spent close to two hours on the grounds. We went inside the great dome (surprisingly uninteresting.) But I’m not going to write any more about the Taj Mahal. You go there to feel that jolt of moving from second-hand knowledge to direct experience and wonder. There’s no recreating that with words.

Since we only had one full day in Agra, we had girded our loins for Serious Sightseeing. We walked back to our B&B, ate breakfast, then caught a tuk-tuk to the gigantic and famous Agra Fort. It’s very impressive, too, but after another hour or so of poking around in it (and more than 11,000 steps logged on my iPhone), I was flagging. We also needed money. The ATM that was supposed to be steps from the fort was closed, according to a local. So we hired another tuk-tuk to take us near the South Gate of the Taj, where Lonely Planet said we would find several ATM machines. We found: narrow lanes jammed with honking tuk-tuks, taxis, pedicabs, bikes, cows, pedestrians, ladies bearing heavy bundles on their heads. We found one ATM that was padlocked shut, and one that spat out rupees for my card (but not Steve’s.)

I think we started to feel burned out while eating a dismal lunch (our first bad meal in India) at a forlorn rooftop restaurant that Lonely Planet had described as a “friendly, family-run…nice choice” for both western and Indian food. Still we soldiered on, returning to the guesthouse to rest for only about 90 minutes before setting out again in yet another tuk-tuk.

Because we’re running dangerously low on insect repellant, we had asked our host, Faiz, where we might buy some. He said no one in the neighborhood would have it for sale. (This struck us as odd, in a country with so many disease-carrying bugs.) Faiz instead arranged for a tuk-tuk driver to take us to a large medical-supply store some distance away.

I guess I was expecting maybe… a shopping mall? With something like a Rite-Aid? You could call where we went a pharmacy, but one unlike any I ever patronized in my long-ago childhood. It was as big as some Rite-AIDS, and lined with hundreds upon hundreds of labeled bins. This shows less than half the interior space.

This shows less than half the interior space.

Customers have to stand at a front counter and tell the clerks what they need. The clerk who came to us appeared never to have heard of insect repellant, but a friendly middle-aged Indian man next to me intervened and explained in Hindi what I wanted. The clerk searched and searched and came back with anti-itching cream, which we rejected. He finally found a little stash of three bottles of citronella oil. We bought one for 85 rupees (about $1.20), even though we doubt it will do much to protect us.

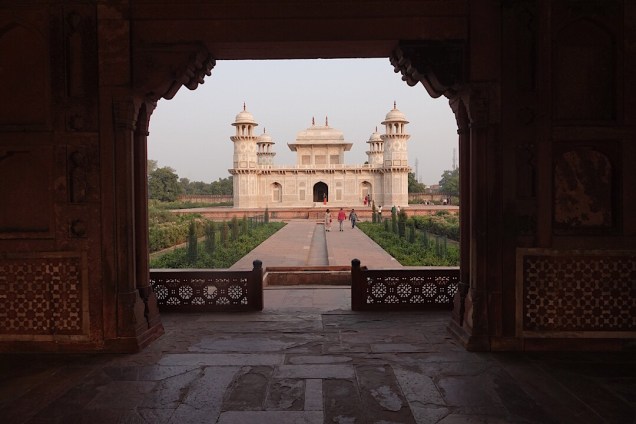

I also needed Kleenex. (My runny nose and cough haven’t improved.) But the pharmacy didn’t sell any. Nor did any of the tiny roadside shops our driver stopped at on our way to the “Baby Taj,” another of Agra’s architectural wonders. Nice, but nothing like Big Mama.

Nice, but nothing like Big Mama.

We spent about 40 minutes there and another half hour at the garden across the river from the big Taj. People say it’s lovely to see the light from the setting sun on the monument, but yesterday afternoon the sun sank into smog so thick it blocked all the color. This was as good as it got.

This was as good as it got.

The driver was supposed to take us back to our guesthouse at this point, but earlier in the day, Steve had managed to make a dinner reservation at the Oberoi Amarvilas. The driver looked surprised when we asked him to take us there. Rooms at this Oberoi (unlike the very reasonably priced Oberoi in Kolkata, where we stayed) run from $900 to more than $1000 a night. We knew dinner would be pricy.

We didn’t care. We yearned for quiet and serenity. To their credit, the staff at the Oberoi didn’t betray any revulsion over how beat up we must have looked. They escorted us through an exquisite garden, through the stunning lobby, to a restaurant where turbaned waiters served us delicious things to drink and eat. We savored every sip, every mouthful.

We also talked at length about whether it was a mistake to stay at Faiz’s guesthouse, which is clean and reasonably comfortable and cost less than half the price (per night) than the dinner we were consuming. But it’s hardly luxurious. Here’s the street in front of Faiz’s home. The road leading to the Oberoi looks quite different.

Here’s the street in front of Faiz’s home. The road leading to the Oberoi looks quite different.

I had an insight. When traveling in India, you can cushion yourself from much of what’s been wearing us down. You can hire people to plan your trip and move you around in air-conditioned cars and buses. You can sleep in places that don’t cost as much as this Agra Oberoi but still are much posher than Faiz’s home. Traveling this way costs a lot more in money but less in stress.

Or you can do what we’ve been doing, mixing up the fancy hotels and palaces with mid-range ones and guest houses and B&Bs; riding on the trains and in the tuk-tuks; eating in some of the local joints.This takes a toll on our nerves and sometimes our mood, but it not only costs less. It gives us what feels like a wealth of information about the way contemporary Indians live. We get to see things like that pharmacy; get to shop at the tiny open stands. Steve and I hunger for that kind of knowledge, and we will go home (if we survive) richer in compassion for what ordinary Indians — not just the poor masses but middle-class ones — put up with. We’ll be stuffed with memories of one great conversation after another. And we’ll better appreciate things like Kleenex and Rite-AIDS and Amtrak.

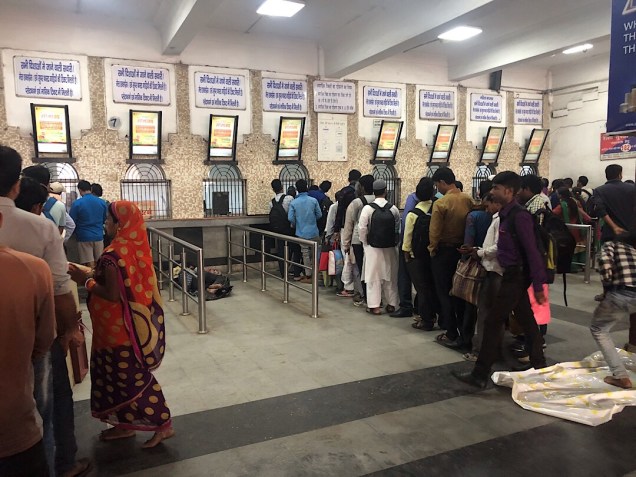

Of course, we still have four weeks of Indian travel ahead of us. Will we hate the place by then? This morning, at least, our glum mood had lifted. We ate a quick breakfast cooked by Faiz’s mother (who lives in the house along with other family members) and bade goodbye to Faiz. We rode in a beautiful new taxi to the train station, walked in, and learned that our train this morning had been delayed. It probably would arrive at least eight hours late. We called Faiz, who hopped in his own car, drove it to the station, collected us, and helped us arrange a private car and driver.

We rode in a beautiful new taxi to the train station, walked in, and learned that our train this morning had been delayed. It probably would arrive at least eight hours late. We called Faiz, who hopped in his own car, drove it to the station, collected us, and helped us arrange a private car and driver. A nice one!

A nice one!

Once underway, I managed to get on the Indian Railways website (by connecting to my iPhone’s hotspot). But I got a message saying there’s no refund “if train is running more than 3 hours late or train is canceled.”

But I got a message saying there’s no refund “if train is running more than 3 hours late or train is canceled.”

No further disaster struck us on the five-and-a-half-four drive… unlike this poor truck that we passed.

unlike this poor truck that we passed.

I’m posting this now from our hotel, which is wonderfully soothing. Tomorrow at 6:30 am, we’ll set off on another attempt to see some wild Bengal tigers. The guidebook says Ranthambore National Park is the best place in Rajasthan to do that.

Set among them are about a dozen structures. The area is breathtaking; even at a distance, it ranks among the greatest ceremonial sites Steve and I have visited: Angkor Wat, Machu Picchu, Teotihuacan.

Set among them are about a dozen structures. The area is breathtaking; even at a distance, it ranks among the greatest ceremonial sites Steve and I have visited: Angkor Wat, Machu Picchu, Teotihuacan.

These ladies were replanting the lawn with individual seeds.

These ladies were replanting the lawn with individual seeds. This is a huge sandstone wild boar– the third incarnation of the god, Shiva.

This is a huge sandstone wild boar– the third incarnation of the god, Shiva. And this is some of what’s carved into his side.

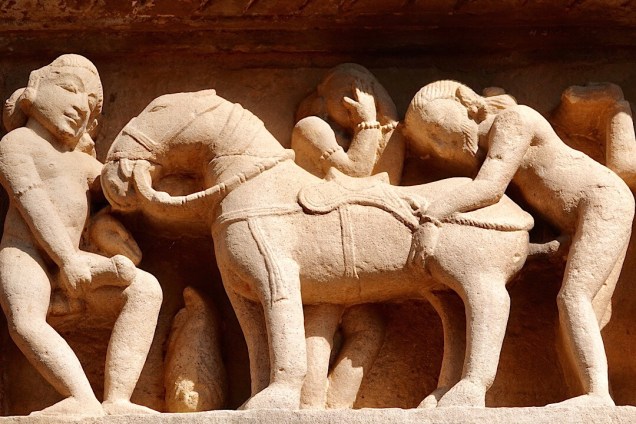

And this is some of what’s carved into his side. …wacky positions from the Kama Sutra, masturbation…

…wacky positions from the Kama Sutra, masturbation… …but it feels like every other aspect of human life is also captured. Soldiers slaughter each other with the aid of war elephants. A famous carving depicts a young woman applying her eye make-up.

…but it feels like every other aspect of human life is also captured. Soldiers slaughter each other with the aid of war elephants. A famous carving depicts a young woman applying her eye make-up. Another girl extracts a thorn from her foot:

Another girl extracts a thorn from her foot: People bathe, stretch, drink together…

People bathe, stretch, drink together… …listen to music.

…listen to music. The carvers’ sense of humor is obvious. In one of the most infamous scenes, a man is fornicating with a horse, while two men on each side await their turn. A third covers his eyes in disgust at the barbarism — except that the carver makes it clear he’s peeking.

The carvers’ sense of humor is obvious. In one of the most infamous scenes, a man is fornicating with a horse, while two men on each side await their turn. A third covers his eyes in disgust at the barbarism — except that the carver makes it clear he’s peeking.

The elephant looks like he’s got a sense of humor too.

The elephant looks like he’s got a sense of humor too. Some of the Jain monks never wear clothes. Like this one. Outside of the four-month-long monsoon season, where they congregate in some location (e.g. Khajuraho this year), the Jain monks wander naked through the countryside, praying and preaching and meditating.

Some of the Jain monks never wear clothes. Like this one. Outside of the four-month-long monsoon season, where they congregate in some location (e.g. Khajuraho this year), the Jain monks wander naked through the countryside, praying and preaching and meditating. One of their only possessions is the brush they carry to sweep insects out of their path to avoiding injuring them.

One of their only possessions is the brush they carry to sweep insects out of their path to avoiding injuring them. The city isn’t crowded, and there’s little traffic, so it feels quiet. A few temples are located in the surrounding farmland, and we cycled past folks drawing water from a well….

The city isn’t crowded, and there’s little traffic, so it feels quiet. A few temples are located in the surrounding farmland, and we cycled past folks drawing water from a well…. ..and kids swimming and bathing in a local stream.

..and kids swimming and bathing in a local stream. We pedaled through a village where a woman was slamming handfuls of cow dung on the facade of her house (home maintenance? We weren’t sure.)

We pedaled through a village where a woman was slamming handfuls of cow dung on the facade of her house (home maintenance? We weren’t sure.) I think it’s the only glimpse we’ll get of rural life in the heart of India. I’ll probably remember it as clearly as the riotous, naughty temple stone tapestry. But we’ve left it behind us now. I’m writing this on a train heading for the heart of Indian tourism. With luck, I’ll post it from our home stay in Agra, about a ten-minute walk from the Taj Mahal.

I think it’s the only glimpse we’ll get of rural life in the heart of India. I’ll probably remember it as clearly as the riotous, naughty temple stone tapestry. But we’ve left it behind us now. I’m writing this on a train heading for the heart of Indian tourism. With luck, I’ll post it from our home stay in Agra, about a ten-minute walk from the Taj Mahal. My photo doesn’t do it justice. It doesn’t clearly show all the small boats congregated in front of the seven platforms or the priest standing on each platform, and of course you can’t hear the continuous bells and the plaintive singing. Every night in Varanasi after sunset, before a vast assembly, the priests go through a complex ritual: blowing into conch shells, wafting incense dispensers, waving great silver candelabras. It’s part religious ceremony; part performance art.

My photo doesn’t do it justice. It doesn’t clearly show all the small boats congregated in front of the seven platforms or the priest standing on each platform, and of course you can’t hear the continuous bells and the plaintive singing. Every night in Varanasi after sunset, before a vast assembly, the priests go through a complex ritual: blowing into conch shells, wafting incense dispensers, waving great silver candelabras. It’s part religious ceremony; part performance art.

Strolling along these “ghats,” as they’re called, is endlessly entertaining. I’ve never felt more like I was on another planet. You see…

Strolling along these “ghats,” as they’re called, is endlessly entertaining. I’ve never felt more like I was on another planet. You see…

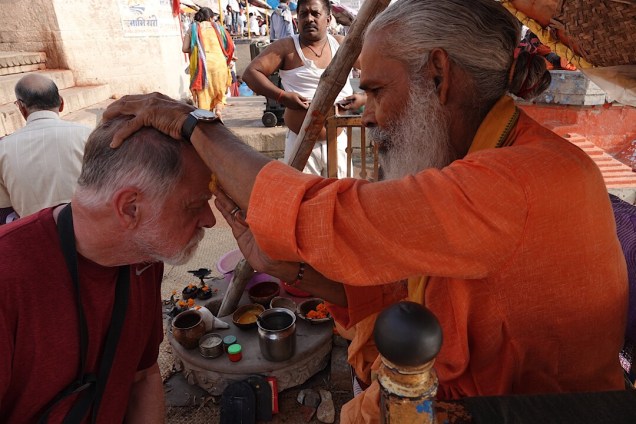

…holy men…

…holy men… …some of whom will bless you. There are…

…some of whom will bless you. There are… …ladies in saris tidying up…

…ladies in saris tidying up… …kids playing street hockey…

…kids playing street hockey… …pilgrims bathing….

…pilgrims bathing…. ..and shopping. These are sealed bottles of Ganga water, ready to take home for your friends. (To our friends, sorry. We resisted.)

..and shopping. These are sealed bottles of Ganga water, ready to take home for your friends. (To our friends, sorry. We resisted.) That’s not a typo. It was sunrise, not sunset. Varanasi’s air appears no cleaner than Kolkata’s.

That’s not a typo. It was sunrise, not sunset. Varanasi’s air appears no cleaner than Kolkata’s. To our surprise, we smelled no ugly odors.

To our surprise, we smelled no ugly odors. This is because the fires burn deodorizing banyan tree wood mixed with sandalwood, we were told.

This is because the fires burn deodorizing banyan tree wood mixed with sandalwood, we were told.

…and carefully weighed for each funeral pyre.

…and carefully weighed for each funeral pyre. The other two nights we spent in a guesthouse that cost $14 a night. Compared to the palace, it was spartan. The rooms were spotless, but tiny. And the 31-year-old owner/operator was smart and knowledgeable and generous-hearted. When he unintentionally dropped and lost one of the paper clips we kept in our passports to mark the page with the Indian visa (which every hotel must photocopy!), we told him it was no big deal. But two days later he presented us with a replacement that he went out and bought for us. After we checked out to move to the palace, he invited us to return for his special spiced tea (masala chai). In the conversation we had while sipping it, he felt like a treasured old friend.

The other two nights we spent in a guesthouse that cost $14 a night. Compared to the palace, it was spartan. The rooms were spotless, but tiny. And the 31-year-old owner/operator was smart and knowledgeable and generous-hearted. When he unintentionally dropped and lost one of the paper clips we kept in our passports to mark the page with the Indian visa (which every hotel must photocopy!), we told him it was no big deal. But two days later he presented us with a replacement that he went out and bought for us. After we checked out to move to the palace, he invited us to return for his special spiced tea (masala chai). In the conversation we had while sipping it, he felt like a treasured old friend. Steve and I sensed a peacefulness on the ghats of Varanasi, and Sonu said he feels it too. As hard as he works and as crazy as the guesthouse operation can get, he told us he tries to spend an hour or so by the river every day. It re-energizes him. I think there’s also beauty there which you can’t miss seeing.

Steve and I sensed a peacefulness on the ghats of Varanasi, and Sonu said he feels it too. As hard as he works and as crazy as the guesthouse operation can get, he told us he tries to spend an hour or so by the river every day. It re-energizes him. I think there’s also beauty there which you can’t miss seeing.

I don’t call myself a Buddhist, but in recent years, I have found much to admire in the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (the northern Indian prince who became the Buddha). About 2600 years ago, he famously found enlightenment in a specific place in India: sitting under a fig tree in what is now the small town of Bodhgaya. When I learned that a direct descendant of that tree was roughly on the path between Kolkata and Varanasi, I wanted to see it.

I don’t call myself a Buddhist, but in recent years, I have found much to admire in the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (the northern Indian prince who became the Buddha). About 2600 years ago, he famously found enlightenment in a specific place in India: sitting under a fig tree in what is now the small town of Bodhgaya. When I learned that a direct descendant of that tree was roughly on the path between Kolkata and Varanasi, I wanted to see it. Sometime in the early afternoon, Steve noticed on our maps app that the train seemed to be headed away from Gaya, but we guessed it would take a turn south at Patna (the capital of the state, Bihar), and arrive at Gaya probably hours late. It was only about 3:30 that an announcement in Hindi caught Deepshri’s ears. “This train isn’t going to Gaya!” she exclaimed! “It’s going to Patna instead!”

Sometime in the early afternoon, Steve noticed on our maps app that the train seemed to be headed away from Gaya, but we guessed it would take a turn south at Patna (the capital of the state, Bihar), and arrive at Gaya probably hours late. It was only about 3:30 that an announcement in Hindi caught Deepshri’s ears. “This train isn’t going to Gaya!” she exclaimed! “It’s going to Patna instead!” Dawn in beautiful downtown Patna, from our hotel window.

Dawn in beautiful downtown Patna, from our hotel window. This was a big challenge for our puzzle-solving skills; we missed catching the 6:45 am express train, but we caught the express at 11:15, which not only left Patna on time; two and a half hours later, it also arrived in Gaya right on schedule. En route we were entertained by a wide-ranging conversation with a banker from Patna (to which about 6 other Indian guys in our immediate vicinity raptly listened.)

This was a big challenge for our puzzle-solving skills; we missed catching the 6:45 am express train, but we caught the express at 11:15, which not only left Patna on time; two and a half hours later, it also arrived in Gaya right on schedule. En route we were entertained by a wide-ranging conversation with a banker from Patna (to which about 6 other Indian guys in our immediate vicinity raptly listened.) The banker and I

The banker and I The mood was calm and serene. Outside the main entrance to the most sacred buildings, we had to deposit our cellphones in a locker and pass through a metal detector. (Apparently some wacko set off a bomb a few years ago.) We also hired a guide who turned out to be excellent.

The mood was calm and serene. Outside the main entrance to the most sacred buildings, we had to deposit our cellphones in a locker and pass through a metal detector. (Apparently some wacko set off a bomb a few years ago.) We also hired a guide who turned out to be excellent. .

. Devotees had prepared this offering to the tree.

Devotees had prepared this offering to the tree. Like this…

Like this… Or this…

Or this… But it was growing dark, so we took another auto rickshaw back to the ugly Gaya flophouse. There we got to bed as early as we could. We knew we had to set the alarm for 4:15 to catch the train to the holiest spot in Hinduism.

But it was growing dark, so we took another auto rickshaw back to the ugly Gaya flophouse. There we got to bed as early as we could. We knew we had to set the alarm for 4:15 to catch the train to the holiest spot in Hinduism. There was no sign of it at 8:30 or 9. Only about 9:10 did this contraption — call it an older brother of the kiddy train that operates next to the San Diego Zoo — chug into the station.

There was no sign of it at 8:30 or 9. Only about 9:10 did this contraption — call it an older brother of the kiddy train that operates next to the San Diego Zoo — chug into the station. Pandemonium ensued as befuddled passengers (us chief among them) tried to figure out where to sit. Rail attendants seemed to be non-existent. But someone finally directed us to places in the “First Class” car, and around 9:30, we were off.

Pandemonium ensued as befuddled passengers (us chief among them) tried to figure out where to sit. Rail attendants seemed to be non-existent. But someone finally directed us to places in the “First Class” car, and around 9:30, we were off. By the time we departed, every seat was full.

By the time we departed, every seat was full. … then beautiful green forests filled with enormous trees or moving along the edge of jaw-dropping precipices.

… then beautiful green forests filled with enormous trees or moving along the edge of jaw-dropping precipices. The train has big windows you can open wide, so at times it felt like we were hiking through those landscapes. It’s an engineering marvel, climbing from under 500 feet above sea level to more than 7000 in less than 50 miles. To accomplish this, it does some fancy tricks that include occasionally backing up and switching onto another track on a higher level. It also cuts across the paved (auto) road often, which is entertaining.

The train has big windows you can open wide, so at times it felt like we were hiking through those landscapes. It’s an engineering marvel, climbing from under 500 feet above sea level to more than 7000 in less than 50 miles. To accomplish this, it does some fancy tricks that include occasionally backing up and switching onto another track on a higher level. It also cuts across the paved (auto) road often, which is entertaining. But by 3:30, our scheduled arrival time, when we were clearly hours from Darjeeling, stuck in a jolting hell overseen by workers who clearly did not care a whit what time got there, with only a hole in a tiny compartment to pee in, and only potato chips for lunch, we were pretty miserable.

But by 3:30, our scheduled arrival time, when we were clearly hours from Darjeeling, stuck in a jolting hell overseen by workers who clearly did not care a whit what time got there, with only a hole in a tiny compartment to pee in, and only potato chips for lunch, we were pretty miserable. They captured images of their kids enjoying pony rides. They shopped for pashminas and visited the ancient Buddhist temple that adjoined our hotel.

They captured images of their kids enjoying pony rides. They shopped for pashminas and visited the ancient Buddhist temple that adjoined our hotel. Some of them did what we did the second day: hiked about a mile to the excellent local zoo (specializing in Himalayan animals). The zoo grounds also contain the marvelous Himalayan Mountaineering Institute.

Some of them did what we did the second day: hiked about a mile to the excellent local zoo (specializing in Himalayan animals). The zoo grounds also contain the marvelous Himalayan Mountaineering Institute. It trains aspiring peak-conquerers and also venerates the memory of past heroes, like Tenzin Norgay, who guided Sir Edmund Hillary to the first conquest of Mt. Everest.

It trains aspiring peak-conquerers and also venerates the memory of past heroes, like Tenzin Norgay, who guided Sir Edmund Hillary to the first conquest of Mt. Everest. The museum displays some of the great sherpa’s gear from that historic climb.

The museum displays some of the great sherpa’s gear from that historic climb. Happily, we were upgraded to a suite, the very one in which a young American student of Asia named Hope Cooke was staying in 1959 when she met and fell in love with the Prince of Sikkim, later marrying him and becoming queen.

Happily, we were upgraded to a suite, the very one in which a young American student of Asia named Hope Cooke was staying in 1959 when she met and fell in love with the Prince of Sikkim, later marrying him and becoming queen. All the facilities today are a bit creaky, but where else have I ever been served five-course meals by white-gloved waters (and coffee kept warm under a knitted cozy)…

All the facilities today are a bit creaky, but where else have I ever been served five-course meals by white-gloved waters (and coffee kept warm under a knitted cozy)… The Windamere’s dining room

The Windamere’s dining room

…and have our height, weight, temperature, and blood pressure checked. Then we were ushered in to see the clinic’s owner, Dr. Sooyoung Kim, an urbane guy dressed in jeans and a casual longsleeve shirt who spoke English like an American. We chatted with him about what we wanted (vaccinations against Japanese encephalitis (for me) and cholera (both of us). He approved our plan and sent us off for processing by his efficient nurse.

…and have our height, weight, temperature, and blood pressure checked. Then we were ushered in to see the clinic’s owner, Dr. Sooyoung Kim, an urbane guy dressed in jeans and a casual longsleeve shirt who spoke English like an American. We chatted with him about what we wanted (vaccinations against Japanese encephalitis (for me) and cholera (both of us). He approved our plan and sent us off for processing by his efficient nurse. But we wouldn’t be able to take the second dose for another week. And during that time, we had to travel to Kolkata via Singapore.

But we wouldn’t be able to take the second dose for another week. And during that time, we had to travel to Kolkata via Singapore.

It surely got warmer than 2 to 8 degrees Celsius (what I think was the recommended temperature range) for several hours. I don’t know what difference that makes. If we don’t get cholera or traveler’s diarrhea, I don’t know if the Dukoral will deserve the credit. But I’d sure like to think it did.

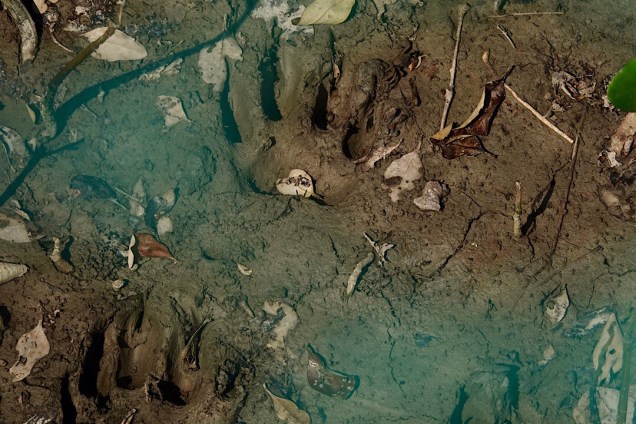

It surely got warmer than 2 to 8 degrees Celsius (what I think was the recommended temperature range) for several hours. I don’t know what difference that makes. If we don’t get cholera or traveler’s diarrhea, I don’t know if the Dukoral will deserve the credit. But I’d sure like to think it did. We didn’t go there to suffer. Rather, we wanted to see one of the geographic wonders of the world. The Sundarbans is the enormous estuary where some of India’s biggest rivers — the Ganges, the Brahmaputra, and others — split into dozens of branches and flow into the Bay of Bengal. The area includes both an Indian and a Bangladeshi section. What grows there, mainly, are mangroves, the shrub which somehow learned to suck up seawater and excrete the salt. The Sundarbans mangrove forest is the biggest on earth. More than 80 species grow so densely you can’t see more then a few feet into them, and they shoot up stick-like “air roots” that can impale anything that steps on them. Despite that, a number of creatures survive in this harsh environment, the most famous being the Royal Bengal tiger.

We didn’t go there to suffer. Rather, we wanted to see one of the geographic wonders of the world. The Sundarbans is the enormous estuary where some of India’s biggest rivers — the Ganges, the Brahmaputra, and others — split into dozens of branches and flow into the Bay of Bengal. The area includes both an Indian and a Bangladeshi section. What grows there, mainly, are mangroves, the shrub which somehow learned to suck up seawater and excrete the salt. The Sundarbans mangrove forest is the biggest on earth. More than 80 species grow so densely you can’t see more then a few feet into them, and they shoot up stick-like “air roots” that can impale anything that steps on them. Despite that, a number of creatures survive in this harsh environment, the most famous being the Royal Bengal tiger. The road wasn’t horrible. We slowed more often for speed bumps than potholes. But the bouncy, uneven ride, the constant swerving and accelerating, the incessant horn-blowing wearied me.

The road wasn’t horrible. We slowed more often for speed bumps than potholes. But the bouncy, uneven ride, the constant swerving and accelerating, the incessant horn-blowing wearied me. The village may be poor and backward, but the Indian ladies still dress sharply.

The village may be poor and backward, but the Indian ladies still dress sharply. …where you can find unexpected beauty.

…where you can find unexpected beauty.

Where DID he go?

Where DID he go? Indian spotted deer grazing near the riverbanks…

Indian spotted deer grazing near the riverbanks… A 5-foot-long monitor lizard enjoying the sun.

A 5-foot-long monitor lizard enjoying the sun. Macaques. We watched this group chase the one guy into the water. They seemed to be mad at him.

Macaques. We watched this group chase the one guy into the water. They seemed to be mad at him. This is a yellow fiddler crab. Don’t you love his eyes?

This is a yellow fiddler crab. Don’t you love his eyes? Most menacing was this mature crocodile. Alligators also ply these waters, but it’s the crocs who are murderous, taking down even tigers when they’re swimming from island to island.

Most menacing was this mature crocodile. Alligators also ply these waters, but it’s the crocs who are murderous, taking down even tigers when they’re swimming from island to island.

Outside its entrance, this version of the goddess preached various civic messages. Note that the evil she’s attacking is a mosquito.

Outside its entrance, this version of the goddess preached various civic messages. Note that the evil she’s attacking is a mosquito.

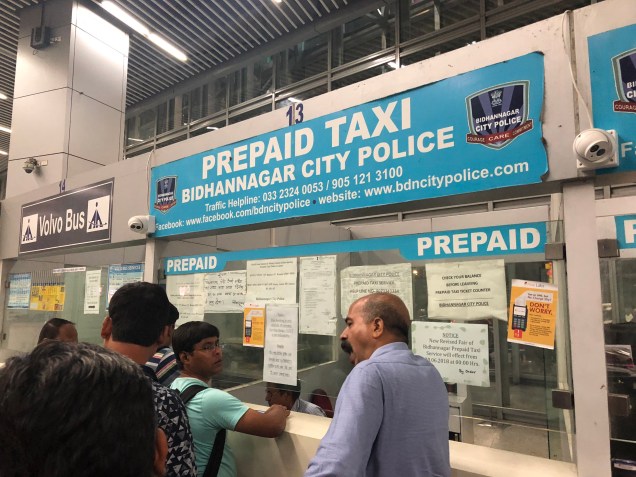

We didn’t reach ours until close to 12:30 (3:30 am Seoul time — and god knows what on our body clocks.) Weirdly, it took only a minute for us to pay for our ride (380 rupees or about $5.15), and out in the street, we quickly located the ancient taxi assigned to transport us. I can only guess that the line had moved so glacially because folks in front of us were going to more complicated destinations.

We didn’t reach ours until close to 12:30 (3:30 am Seoul time — and god knows what on our body clocks.) Weirdly, it took only a minute for us to pay for our ride (380 rupees or about $5.15), and out in the street, we quickly located the ancient taxi assigned to transport us. I can only guess that the line had moved so glacially because folks in front of us were going to more complicated destinations. Occasionally we passed a floodlit shrine containing what appeared to be a multi-armed goddess.

Occasionally we passed a floodlit shrine containing what appeared to be a multi-armed goddess. In nine days, Steve and I will depart on the longest trip of our lives: seven weeks in India, a week and a half in Sri Lanka, and a few days of South Korea and Japan (in transit). As I’ve planned the arrangements, the question I’ve been asked most is: aren’t you afraid of getting sick?

In nine days, Steve and I will depart on the longest trip of our lives: seven weeks in India, a week and a half in Sri Lanka, and a few days of South Korea and Japan (in transit). As I’ve planned the arrangements, the question I’ve been asked most is: aren’t you afraid of getting sick?