After spending 10 days hop-skipping- and jumping across the Pacific, followed by two weeks in wild Papua New Guinea, who in their right mind would then tack on a week and a half in Japan?

That would be moi. I had several reasons.

- I scored awesome seats for us (Business Class on Singapore) to LAX from Tokyo using points.

2) My love for Japan is bottomless; I will embrace any chance to spend time there.

3) Steve and I had never visited Hokkaido, the large island in the north of Japan. Maybe a detour there in early October would give us what we’d never experienced before: exposure to Japan’s magnificent fall foliage.

As readers of this blog may recall, we traveled in Japan last year for the first time in ages. I had hoped to experience the celebrated autumn colors then. But we were mostly in the south (Kobe, Shikoku, Hiroshima, Kyoto and Osaka), and we saw only subtle hints of the vivid palette that would soon cover the landscape. Hokkaido, on the other hand, is the northernmost of Japan’s four main islands. I studied websites devoted to predicting when and where the leaves in Hokkaido would turn, and I planned a post-Papuan itinerary accordingly.

We didn’t see much of anything when our flight landed at Hokkaido’s main airport late Thursday afternoon (October 2). We’d reserved a car, and by the time we got off the shuttle bus at Budget’s office, filled out the paperwork, and checked out our wheels (a Toyota Yaris), the sun was sinking fast. The 90 minutes that followed began well; Google maps (in English!) worked using AirPlay. But when we turned off the tollway onto the road leading into the mountains, things got harrowing. With the light almost gone, a deer leapt out of the brush and crossed the road a few car lengths in front of us. Not long afterward the sky was black; we glimpsed another deer lurking by the roadside.

Only our headlights illuminated the switchbacks, and the worst moment came when our windshield began to fog up and I couldn’t figure out how to defrost it. (Have I mentioned the road had no shoulder and almost no pull-outs?) We finally arrived, unscathed, at our hotel around 6:45 pm but to me it felt like it was close to midnight.

The next morning I opened the curtains to see…

The weather was so glorious, however, nothing could dampen my mood. Steve and I spent the day poking around Jozenkai Onsen — a long-established mecca for hot springs lovers. In the center of the tiny town, you could…

A sign warned that brazen crows might snatch your eggs if you weren’t careful.

We prowled through a cave filled with statues of Buddhist deities…

…decided NOT to hike into the bear-infested woods.

…admired the (mostly green) trees surrounding the town’s picturesque bridge.

We also stopped in at the local tourist office to ask if we might find more fall colors anywhere nearby. A helpful staffer suggested we visit the Sapporo Kokusai ski resort about 30 minutes away. She said we might find a more classical autumnal scene at the top of the ropeway there.

When we arrived at the resort Saturday morning, people were bustling about, setting up for the day’s “autumn foliage festival.” Burly chefs were slapping big chunks of pork on an outdoor grill; food stalls were opening. We hopped on one of the gondolas and did see more mustard and vermilion hues as we neared the top.

We couldn’t linger at the festival because we had to drive several hours to reach Daisetsuzan, the largest national park in all Japan. It’s smack in the middle of Hokkaido, encompassing a chain of mountains, of which Mt. Asahidake is the tallest. I’d wanted to spend two nights at a lodge at the base of the mountain because I’d read that this is the part of Japan where the trees usually change color first.

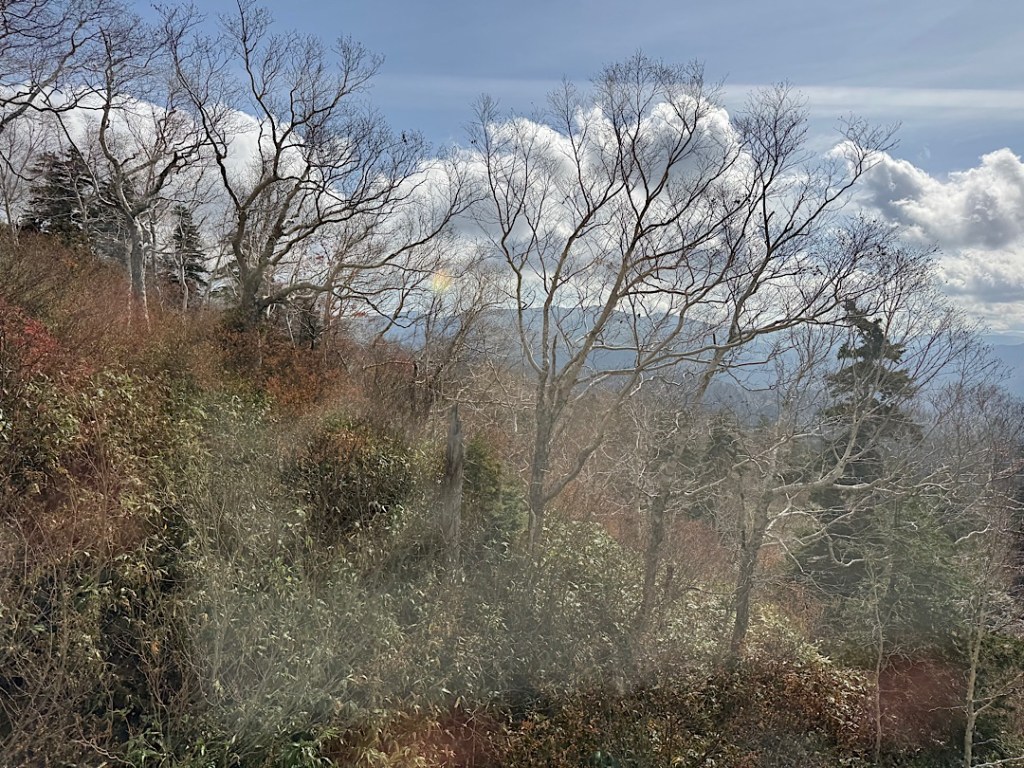

Once again, we didn’t reach our lodgings until late afternoon. We took Japanese baths in the lodge’s in-house spas (supplied with hot water from the local springs.) Like the other guests, Steve and I wore our lodge-issued pajamas and slippers to the restaurant, where a multi-course French mea was included with our room cost. The next morning, we walked to the nearby “ropeway” up the mountain, and I realized most of the trees had already turned color and lost their leaves.

It was impossible to feel too disappointed, given the marvelous views from the loop trail at the top.

That afternoon we took more baths; gorged on a Japanese teppanyaki meal in the restaurant. On our drive the next day to Sapporo, last stop on our Hokkaido tour, I decided it was next to impossible to plan a visit to Japan specifically to see the leaves. If you lived in Japan you could check online sources and dash out to one site or another when the time was right. Or maybe you could enjoy what you saw from your front door. But when you’re booking plane tickets to fly in from more than 5000 miles away, who could predict the complex phenomenon? (Remind me never to try to catch the peak cherry-blossom bloom.)

Our drive to Sapporo was pretty colorful, winding as it did through a region known for flower crops.

We turned in the rental car…

Then we had three nights and two full days in Sapporo, Japan’s 5th largest city. We filled them with pleasant activities.

Local folks also were gobbling up seasonal street food.

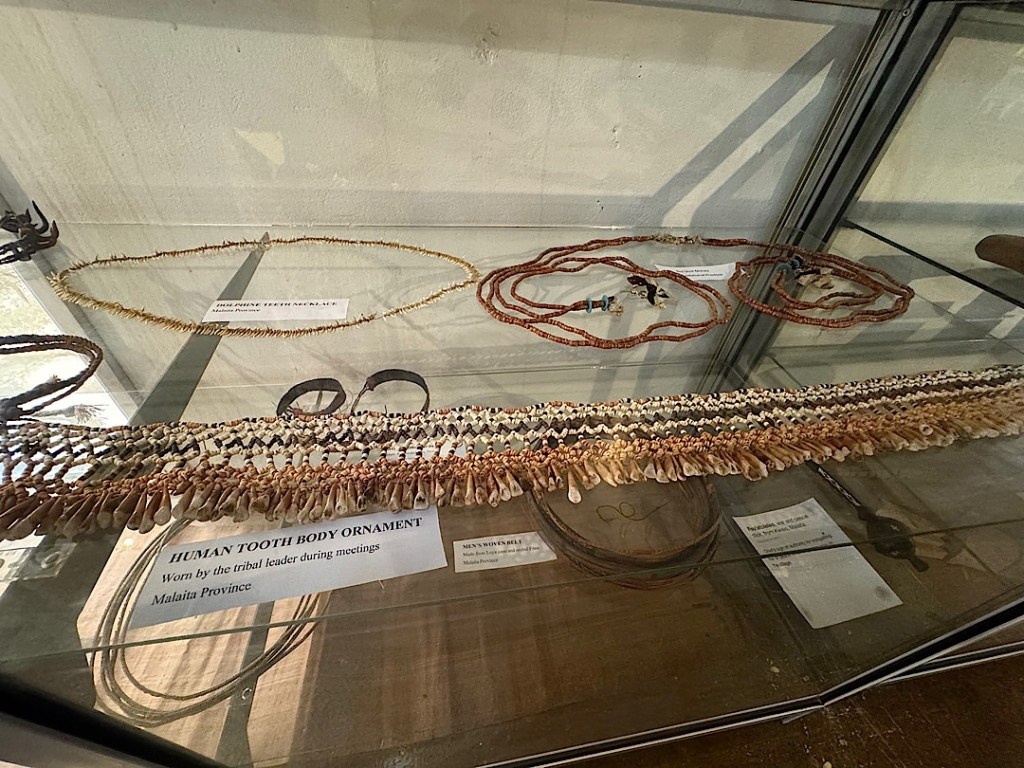

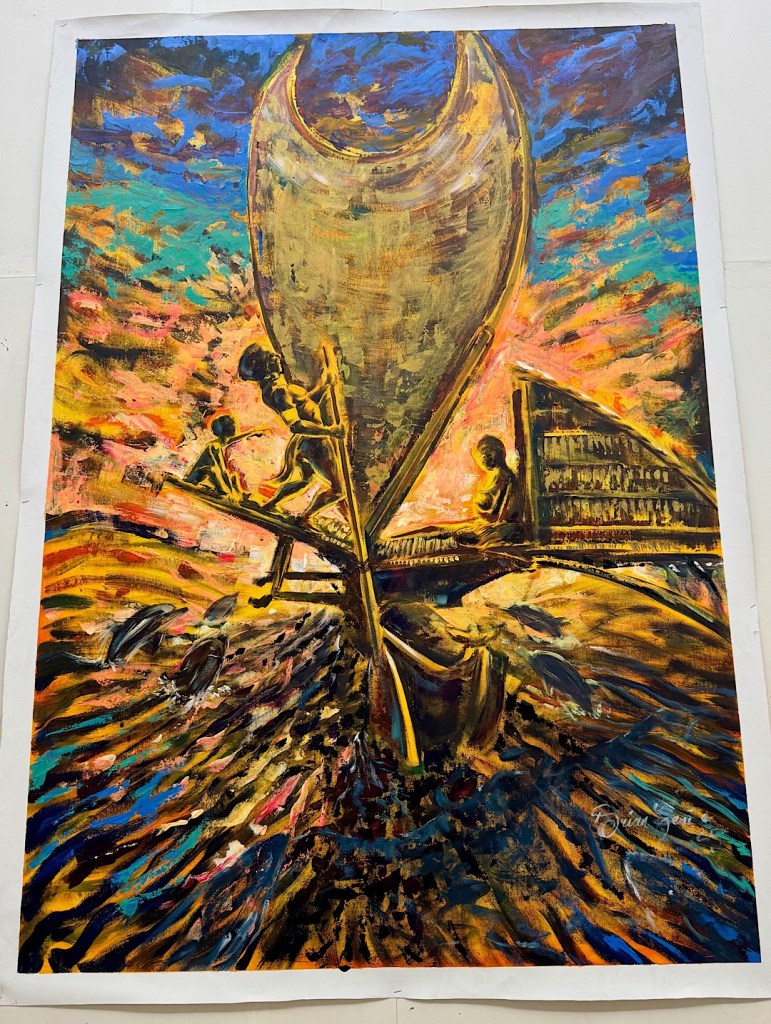

In a couple of local museums, we learned about Hokkaido’s history. This reinforced our impression that Hokkaido is Japan’s Alaska. Its native population (the Ainu) lived in ways Alaska’s natives would have understood. When the monied powers from Honshu took over the island in the mid-1800s and made it part of Japan, they oppressed the Ainu people in ways that depressingly resembled what was going on in Alaska around the same time. Like Alaska, Hokkaido has big landscapes, big animals. (All those bears! All those deer.) People tend to feel more free to experiment.

Seibei Nakagawa was such a young man. One hundred and sixty years ago, when he was 17, he stowed away on a boat heading for Europe (an action punishable by death at the time.). In Germany he learned how to brew beer and became the first certified Japanese beer brewer. When he returned to Japan, he became the first brewmaster at the first-ever Japanese brewery, named after the city where it was founded in 1876.

For our last dinner in Japan, Steve and I headed to the beer garden on the grounds of that original Sapporo Beer facility. We’d made an online reservation for a meal that would allow us to quaff an unlimited amount of beer and consume an unlimited quantity of one of Hokkaido’s most famous dishes — jingisukan. That word is a Japanese rendition of “Genghis Khan.” The dish requires diners to grill their own meat and vegetables on a cast-iron dome-shaped skillet supposedly inspired by the shape of Genghis Khan’s helmet.

The Sapporo Brewery’s “Biergarten” has several restaurants. We chose the largest one, which was rocking with laughter and conversation when we arrived a little after 6. At our table we found a skillet, a cube of lard, and two plates, one holding thinly sliced mutton. The other was heaped with sliced onions, cabbage, and bean sprouts.

We selected our first steins of beer from among the five types on draft. Back at our table, we melted the cube of fat and grilled the lamb (delicious, dipped in a salty sauce). We cooked and ate the veggies, then felt bewildered. Where were the other meats and vegetables supposedly included in our meal?

Finally, we figured out that we had to select them using a special digital tablet on our table. Once ordered, one of the many robots circulating throughout the room would bring the additional dishes to us.

Fueled by the beer, entertained by the cooking and the robots, sated by all the grilled lamb and beef and pork and chicken and some veggies, we walked out into the windy night. Again it was too dark to see much color anywhere. Again, that was okay.