I’m not a wildlife expert, and maybe even the experts don’t know what the future holds for bonobos. But what I want to say is: after visiting the Congo, I feel optimistic.

I’m not a wildlife expert, and maybe even the experts don’t know what the future holds for bonobos. But what I want to say is: after visiting the Congo, I feel optimistic.

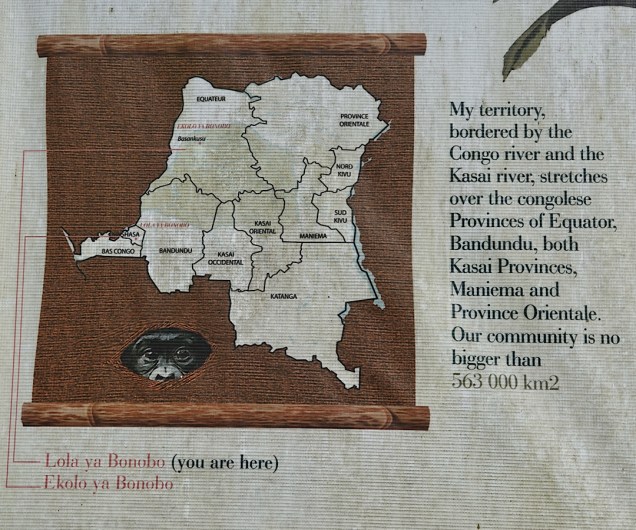

That may be naive. The DRC is one of the most corrupt countries on earth. Its national politics are still in turmoil. Atrocities continue to unfold in the war-torn east, where Ebola has broken out again. And yet… the biggest threat to bonobos isn’t habitat loss, as it is for so many animals in so many places. Congo still has plenty of equatorial rainforest where bonobos can thrive. The bonobo population has plunged because Congolese people eat them. And even that isn’t as bad as it sounds. People don’t think bonobos are endowed with any magical properties (like rhinos, for example, burdened with their theoretically aphrodisiacal horns.) Bonobos are just meat, for which Africans have a big appetite.

Still, just as most humans (even hungry ones) don’t eat other humans, when people learn how similar bonobos are to humans, they can change their minds about bonobos’ place on the menu. And if protecting bonobos instead of eating them can make communities more prosperous, folks can be marshaled to protect them.

Suzy Kwetuenda at Lola ya Bonobo has spent countless hours talking to Congolese villagers in the rainforest about why bonobos deserve protection. She says some of them bristle at the notion of outsiders trying to stop them from eating their bush meat. But she retorts, “You know, we are lucky to be the only ones in the world to have bonobos! They are very precious. The BIG value of bonobos is not in your stomach! It’s very important to have bonobos for development. If you protect them, this area will have more and more visitors. They will come and help you!”

Suzy Kwetuenda at Lola ya Bonobo has spent countless hours talking to Congolese villagers in the rainforest about why bonobos deserve protection. She says some of them bristle at the notion of outsiders trying to stop them from eating their bush meat. But she retorts, “You know, we are lucky to be the only ones in the world to have bonobos! They are very precious. The BIG value of bonobos is not in your stomach! It’s very important to have bonobos for development. If you protect them, this area will have more and more visitors. They will come and help you!”

This has always been a core premise of the Lola team: that the communities surrounding any bonobo release site must see concrete benefits from fighting against the hunters and poachers. Les Amies des Bonobos du Congo and its US-based fundraising arm, Friends of Bonobos, don’t have huge budgets. The money has come mostly from small and medium-sized donors. But a part of those limited resources has been devoted to improving the schools, infrastructure, health care and other services near the Ekola ya Bonobo release site. In the ten years since the Lola team began releasing bonobos back into the wilderness, more and more of the bonobos’ neighbors have become believers.

I’ve seen first-hand how a similar approach has worked in Uganda. There tourists who come from around the world to see mountain gorillas have become an engine of prosperity. Ugandan communities that have benefited now see the animals as a priceless resource. It’s possible to imagine something similar unfolding in the Congo.

What Claudine Andre has accomplished in the last 25 years also fills me with admiration and awe. Starting from nothing, she’s built a team that’s adept at saving baby bonobos on the verge of death. These survivors now routinely thrive in the garden that is Lola. The team also now knows what’s required to successfully reintroduce these very special creatures into the wild. (Only one of the 60-odd reintroduced bonobos has died, a youngster who was bitten by a poisonous snake.) And back at Lola more than 30,000 Congolese school kids already have visited Lola and been inspired by these stories.

It saddens me that so many people still don’t know what bonobos are. (I’ve gotten a lot of blank stares when I’ve mentioned our recent travel plans.) But that can change. A hundred years ago no one had heard of pandas.

A hundred years from now our closest animal relatives could be thriving in the African rainforests, showing us a different model for primate behavior than that demonstrated by chimpanzees and us. If that happens, a lot of things will have made it happen.

Some have already unfolded. Claudine has already dedicated a big chunk of her life to the bonobos’ preservation. Field researchers and veterinarians and the sanctuary crew and others have already learned a lot about what it takes to keep bonobos flourishing. But more will be required. Humans all over the planet will need to recognize bonobos as readily as they do pandas, and many will donate money to help them out. Congolese people will have to learn to treasure them.

That would be the happy ending to the bonobos’ story. Maybe it won’t come to pass, but it should. I’m hoping it will.

Then we heard from Claudine André, Lola’s founder, that the center city, where all the ex-patriots live, was very nice, with some good hotels and many restaurants. She claimed that the cost of living there was the second highest in the world (after Luanda in Angola). When Steve broached the question of whether a little tour might be possible, Claudine made it possible.

Then we heard from Claudine André, Lola’s founder, that the center city, where all the ex-patriots live, was very nice, with some good hotels and many restaurants. She claimed that the cost of living there was the second highest in the world (after Luanda in Angola). When Steve broached the question of whether a little tour might be possible, Claudine made it possible.

…and views of Brazzaville, just across the river.

…and views of Brazzaville, just across the river.

The terrace commanded good views of the river. The rapids begin here, and soon become so violent that boat traffic between Kinshasa and the ocean is impossible.

The terrace commanded good views of the river. The rapids begin here, and soon become so violent that boat traffic between Kinshasa and the ocean is impossible.

The Congolese bonobo sanctuary has three enclosures, a word that to me evokes the image of a cage. But nothing could be more misleading. Lola’s enclosures are wild jungle, ranging in area from 15 to 38 acres. A canopy of trees tower over undergrowth so dense you can’t see more than a few feet into it. The bonobos disappear into this bush every day. Those who have tracked them report that they nap, play, snack on leaves and fruit. But a couple of times daily, the humans appear bearing supplemental rations: starchy balls made fresh every day from corn, flour, and other nutrients, as well as fruit, vegetables, tubers, and sugar cane chunks (a natural toothbrush). At those times, the troupe ambles down to the shore to enjoy the goodies.

The Congolese bonobo sanctuary has three enclosures, a word that to me evokes the image of a cage. But nothing could be more misleading. Lola’s enclosures are wild jungle, ranging in area from 15 to 38 acres. A canopy of trees tower over undergrowth so dense you can’t see more than a few feet into it. The bonobos disappear into this bush every day. Those who have tracked them report that they nap, play, snack on leaves and fruit. But a couple of times daily, the humans appear bearing supplemental rations: starchy balls made fresh every day from corn, flour, and other nutrients, as well as fruit, vegetables, tubers, and sugar cane chunks (a natural toothbrush). At those times, the troupe ambles down to the shore to enjoy the goodies.

We saw little to nothing that looked like competition. It felt more like a lazy picnic in the steamy morning heat.

We saw little to nothing that looked like competition. It felt more like a lazy picnic in the steamy morning heat.

I didn’t understand everything I’d just seen, but I got the big picture. Maybe I was projecting my feelings on them, but it looked like the end of another beautiful day in a very special place.

I didn’t understand everything I’d just seen, but I got the big picture. Maybe I was projecting my feelings on them, but it looked like the end of another beautiful day in a very special place. On this trip, I have learned it’s more fun to watch baby bonobos play than it is to watch many movies. The action is almost nonstop. They sock each other; pounce. One chases another, catches up, and smashes into him. They tickle each other and make a noise that sounds like panting, but it’s not; it’s the sound of bonobo laughter. Sometimes they go too far and someone gets hurt. Ear-piercing shrieks erupt. Others may beat up the bully in retaliation. The smallest ones never stray far from their surrogate mothers. Older ones sometimes mimic copulation. They’re far too young to actually have sex. It’s just instinctive, practice with the tool they will use soon use daily to diffuse social tensions.

On this trip, I have learned it’s more fun to watch baby bonobos play than it is to watch many movies. The action is almost nonstop. They sock each other; pounce. One chases another, catches up, and smashes into him. They tickle each other and make a noise that sounds like panting, but it’s not; it’s the sound of bonobo laughter. Sometimes they go too far and someone gets hurt. Ear-piercing shrieks erupt. Others may beat up the bully in retaliation. The smallest ones never stray far from their surrogate mothers. Older ones sometimes mimic copulation. They’re far too young to actually have sex. It’s just instinctive, practice with the tool they will use soon use daily to diffuse social tensions.

We heard all their names, but we only memorized one: Balangala, that of a 5-year-old male, the most confident member of the gang. One morning we watched him climb a large bamboo stalk that was growing into the enclosure. His weight bent it over, and he jumped from it onto a trampoline. After a while he lured most of the younger ones up onto it with him. Eventually the stalk broke, and the moms had to call for a staff member to cut and haul it away.

We heard all their names, but we only memorized one: Balangala, that of a 5-year-old male, the most confident member of the gang. One morning we watched him climb a large bamboo stalk that was growing into the enclosure. His weight bent it over, and he jumped from it onto a trampoline. After a while he lured most of the younger ones up onto it with him. Eventually the stalk broke, and the moms had to call for a staff member to cut and haul it away.

The nonstop Rwandair flight lifted off the tarmac about 20 minutes late, but the pilots made up almost all of the time. In the Kinshasa airport, it took only a few minutes for an immigration officer to stamp our passports, then we moved to the baggage-claim area. Before we could proceed to the carousel, a lady officer at the health-screening station demanded our yellow-fever injection records. I froze for a moment, trying to remember where I’d stashed them. But I found them and showed them to her, and she waved us on. Our bags showed up. (We travel with carry-ons but their weight exceeded the Rwandair limit.) Outside the front doors, Lola’s driver, Constant, was waiting with a sign. In short order, we were inching through Kinshasa traffic toward the bonobo sanctuary in a Land Cruiser.

The nonstop Rwandair flight lifted off the tarmac about 20 minutes late, but the pilots made up almost all of the time. In the Kinshasa airport, it took only a few minutes for an immigration officer to stamp our passports, then we moved to the baggage-claim area. Before we could proceed to the carousel, a lady officer at the health-screening station demanded our yellow-fever injection records. I froze for a moment, trying to remember where I’d stashed them. But I found them and showed them to her, and she waved us on. Our bags showed up. (We travel with carry-ons but their weight exceeded the Rwandair limit.) Outside the front doors, Lola’s driver, Constant, was waiting with a sign. In short order, we were inching through Kinshasa traffic toward the bonobo sanctuary in a Land Cruiser.

…with several individuals advancing upon him.

…with several individuals advancing upon him. Steve started to ask a question, but Claudine signaled for him to keep his voice down. She knew, we later learned, that if Oshwe realized strangers were close at hand, he would want to investigate. He’d be much less willing to follow the keepers and the treats with which they were trying to lure him.

Steve started to ask a question, but Claudine signaled for him to keep his voice down. She knew, we later learned, that if Oshwe realized strangers were close at hand, he would want to investigate. He’d be much less willing to follow the keepers and the treats with which they were trying to lure him.

We had scored inexpensive tickets traveling on Alaska Airlines from San Diego to Boston, and then continuing on Qatar Airways to Doha, the capital of Qatar. These tickets would enable us to stay in Doha (a place we’ve never visited before) for three nights before continuing on to Entebbe in Uganda.

We had scored inexpensive tickets traveling on Alaska Airlines from San Diego to Boston, and then continuing on Qatar Airways to Doha, the capital of Qatar. These tickets would enable us to stay in Doha (a place we’ve never visited before) for three nights before continuing on to Entebbe in Uganda.

More than eleven and a half hours after we’d entered the airport, our 747 lifted off from the tarmac.

More than eleven and a half hours after we’d entered the airport, our 747 lifted off from the tarmac.