Chasing eclipses is dangerous. The risks aren’t physical but emotional. Traveling anywhere to experience this particular outdoor activity — brief as it is — requires planning and making commitments months or even years ahead of the actual event. If after all that the weather doesn’t cooperate, you can wind up seeing only a fraction of what you’d dreamed about. You could feel devastated.

Steve and I chose to chase Monday’s big American eclipse in Austin mainly because this part of Texas is reputed to have something like 300 days of annual sunshine. (Also, neither of us had ever been to Austin before.) When my iPhone weather app began forecasting Austin’s eclipse-day conditions 10 days ago, my heart sank to see all the clouds. I told myself conditions could change and did my best to put it all out of my mind.

The forecasts got harder to ignore once we arrived here. We’d decided to view the eclipse at a big organized site in Waco (about an hour and a half away, on the centerline, with a consequently long span of total darkness.) But rain had appeared in Waco’s forecasts for Monday and Tuesdays, and by Sunday afternoon, it looked like violent weather — thunder and lightning, huge hail, maybe even a tornado or two — could rip through the area some time Monday afternoon. (Totality would begin at 1:38.) The thought of getting stuck on a freeway in post-eclipse traffic with a Texas tornado spinning toward us was scary enough to make us all consider staying in Austin, even though the moon would cover the sun for only a minute or so (versus more than 4 minutes in Waco). We finally resolved to wait and see what Monday morning brought.

By then, the weather predictors seemed to be suggesting any violent storms would not take shape until late afternoon. So we piled into our van and headed north, under skies that still looked unfriendly.

The outlook began to brighten about a half hour later. Tiny patches of blue sky appeared, illuminated by glimpses of sun.

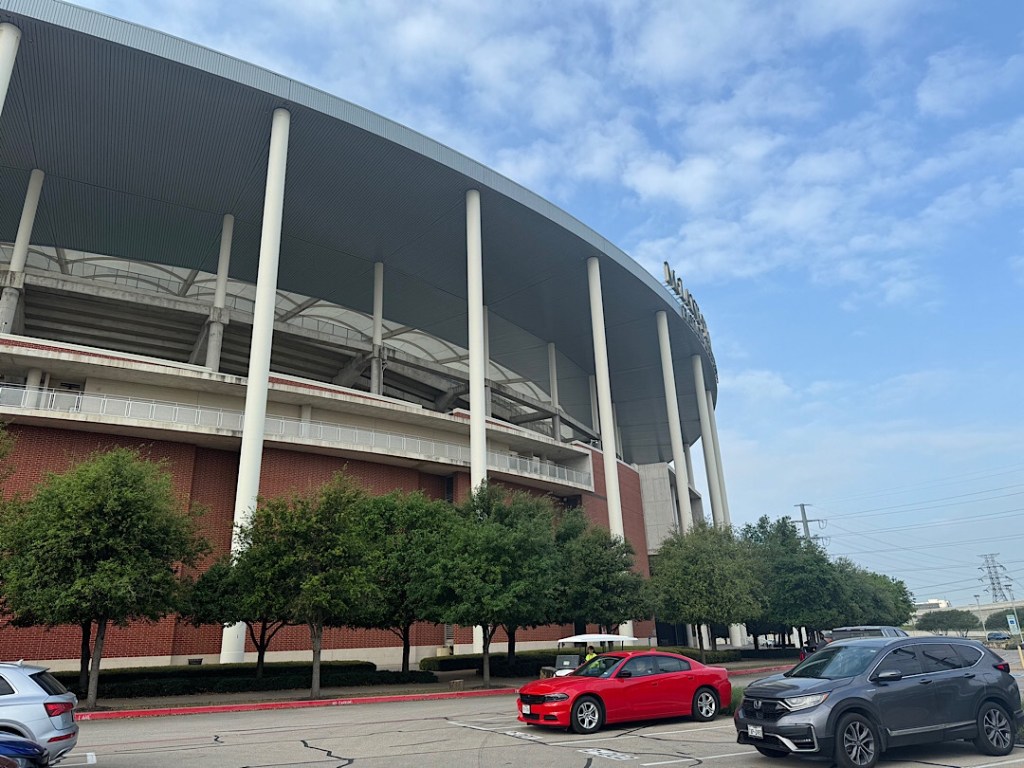

By the time we reached the parking lot at Baylor University, site of our Eclipse Over Texas tickets, it almost felt like a sunny day.

With four hours to go until totality, we walked a little over a mile to the Dr. Pepper Museum in the center of town, where we learned that too many other eclipse-chasers had had the same idea.

The sun was blazing by then, but the line crawled. After a while, we gave up and returned to Baylor’s eclipse-viewing area. The crowd was growing.

I didn’t mind the two-hour wait for totality. Steve and our friend Leigh braved horrendous lines to buy some of the overpriced food-truck offerings. (Event organizers had forbidden bringing in any picnic fare.) I chatted with Donna and Mike; the people-watching also was amusing.

Like so many others in the crowd, I kept an anxious eye on the sky.

The moon sliced its first thin piece out of the sun around 12:20. You could see this marvel through your eclipse glasses, but as I’ve learned from previous total eclipses, no immediate impact on the earthscape is detectable. On Monday, it took at least another 30 minutes for the light to strike my eye as colder, somehow deader than normal. This sense intensified as more and more of the sun was lost.

In those last few minutes, I felt a surge of pure joy. Forecasts be damned! The fragile crescent of remaining sun faced no threat of obliteration from mere clouds. We would see everything as it slipped behind the moon and the world chilled and dimmed, abruptly. Thousands of us simultaneously dropped our cardboard glasses, tilted our heads back, and gaped. People cheered. Some of us screamed.

I noticed different things, this fourth time of viewing a total eclipse. Dark as the sky became, I saw no stars, only Venus and Jupiter. (I have no idea why it would have appeared less dark in Texas than in some of my previous total eclipses.) Even without a telescope or fancy camera and lens, we all could see a glowing orange protuberance at about the 4 o’clock position of the orb: solar flares that someone later said were likely the size of a couple of Earths and more than 10 million degrees.

Something about that perfect alignment — the sun, the moon, my brain, surrounding by the cold gloom of space — electrified me. Then the burst of the first bit of sun re-emerging, more dazzling than anything on earth.

En mass, the crowd scrambled to gather our possessions and begin streaming to the parking lot and shuttle buses. Even though the sun would continue to be uncovered for another hour, mundanity was fully restored.

We tore back to Austin at 70 miles an hour; no traffic ever materialized. It was just one more miracle, one more thing to add to the deep sense of wonder and gratitude.