We didn’t go to Kodagu looking for elephants. We got interested in the area when a friend who has worked and traveled for pleasure in India told us Kodagu was a spice capital of south India, dense with gorgeous jungle. Then another friend put us in touch with an Indian friend who lives in Bangalore and owns two coffee plantations in Kodagu (also known as Coorg, the old British name). I emailed Sheila, asking if we might meet for a lunch, and in an amazing display of generosity, she invited us to stay in the guesthouse on one of her plantations. We made plans to spend three nights.

We didn’t go to Kodagu looking for elephants. We got interested in the area when a friend who has worked and traveled for pleasure in India told us Kodagu was a spice capital of south India, dense with gorgeous jungle. Then another friend put us in touch with an Indian friend who lives in Bangalore and owns two coffee plantations in Kodagu (also known as Coorg, the old British name). I emailed Sheila, asking if we might meet for a lunch, and in an amazing display of generosity, she invited us to stay in the guesthouse on one of her plantations. We made plans to spend three nights.

I haven’t written anything about our time in Bangalore and Mysore because we only had two nights in each. Both look more prosperous than any place we visited in the north, but sadly the air and traffic in Bangalore (“the Silicon Valley of India”) still wasn’t great. By far the highlight for us there was our rollicking three-plus-hour lunch with Sheila — a commanding, cosmopolitan lady with a surfeit of interesting opinions and insights and abundant good humor.

She had worried we might get bored with two and a half days in Kodagu, but this did not come to pass. I don’t know why the district isn’t on every Indian visitor’s list. For centuries (millennia?), Kodagu was an independent little state run by hundreds of clans. The clansmen were warriors but also farmers, growing rice along with spices and eventually coffee. Black pepper grows wild here. Trying to find a way to get to it is what led Christopher Columbus to stumble upon North America.

Kodagu didn’t become part of India until the 1950s, and it sounds like many folks today would like to go back to the independent old days. Living in their fertile valleys, shielded from the rest of the world by rugged mountain forests and the dangerous animals who inhabit them, blessed with clean air and a mild climate, Kodagu is a shangri-la — not just for people but for elephants.

We started our first day with elephants. Sheila’s farm manager, Arthur, found us a taxi ($43 for the whole day), and the driver headed northwest for an hour or so. Our destination was the Dubare Elephant Camp, an operation of the state (Karnataka) forest department. I sort of expected this to be a tourist attraction, and it was, but only in the loosest possible sense of that term.

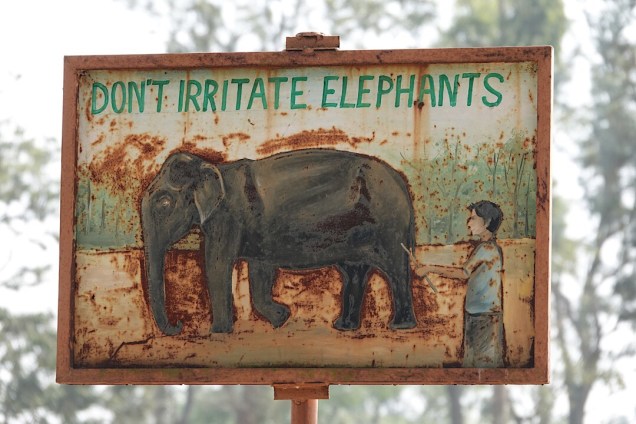

We parked near a bank of the Cauvery River and joined a long queue of Indians waiting to board launches to ferry them to an opposing bank (43 cents per person for the boat ride; 29 cents for the camp admission). In about 15 minutes, Steve and I made it aboard a boat and quickly reached the camp. In the hour and a half we were there, no person, no signs, no brochures told us anything about what the camp is and how it functions. Maybe the Indians thought it was irrelevant. Most folks didn’t come here for helpings of wildlife education: the draw was watching the residents get their morning bath.

In about 15 minutes, Steve and I made it aboard a boat and quickly reached the camp. In the hour and a half we were there, no person, no signs, no brochures told us anything about what the camp is and how it functions. Maybe the Indians thought it was irrelevant. Most folks didn’t come here for helpings of wildlife education: the draw was watching the residents get their morning bath.

Young men were riding big old males and females and youngsters from an upper holding area down to the river… then using that ancient Asian-elephant-control tool, the hook, to make them lay down in the water…

then using that ancient Asian-elephant-control tool, the hook, to make them lay down in the water… or stand patiently while their tusks were cleaned with a sand-paste rub.

or stand patiently while their tusks were cleaned with a sand-paste rub.

Poke this baby into the tender spot behind one of those big ears, and you can get a 10,000-pound beast to do what you want!

Poke this baby into the tender spot behind one of those big ears, and you can get a 10,000-pound beast to do what you want!

For an additional 200 rupees ($2.87), one could go down onto the beach and join in the elephant-spa activity. I (naturally) could not resist, but Steve claimed he didn’t want to get wet and so opted to stay on the cliff top and take pictures.

Down on the beach, I edged up to the action, simply watching for a while. It was hard to tell what the elephants thought.

It was hard to tell what the elephants thought. It didn’t look like they hated it. But was it pleasurable?

It didn’t look like they hated it. But was it pleasurable?

Once or twice, one of the young mahouts interacted with a visitor… …as when one wrapped his charge’s trunk around this young lady’s neck, in response to a photo request. But most of the guys ignored the crowd gaping at them and concentrated instead on scrubbing the tough hides.

…as when one wrapped his charge’s trunk around this young lady’s neck, in response to a photo request. But most of the guys ignored the crowd gaping at them and concentrated instead on scrubbing the tough hides. They reminded me of car-wash attendants, irritable because of the long line of customers awaiting service.

They reminded me of car-wash attendants, irritable because of the long line of customers awaiting service.

I finally petted several animals… I tried to communicate good will with my touch. I ran my fingers over a few tusks, the source of so much elephant suffering and death. Then I rejoined Steve, and we walked to the high ground, where we found workers wrapping up brown rice within handfuls of hay.

I tried to communicate good will with my touch. I ran my fingers over a few tusks, the source of so much elephant suffering and death. Then I rejoined Steve, and we walked to the high ground, where we found workers wrapping up brown rice within handfuls of hay.

It did look to me like they enjoyed getting the tasty packages.

It did look to me like they enjoyed getting the tasty packages.

We made a couple of other touristic stops that day — toured a nature park; visited a large enclave of TIbetan Buddhist exiles. But our quirky, magical visit to the pachyderms overshadowed everything for me. That and the lunch we had with a friend of Sheila’s.

He met us near the nature park and took us to an exquisite riverside resort for lunch. Madhu is an amazing character: a coffee grower himself, but also a consultant to coffee growers all over the planet. His special (U.N.-recognized) expertise is in sustainable cultivation practices. We talked about coffee-growing and many other things; among them, the local elephants.

“You can kill a man and get away with it,” he declared. “But if you kill an animal here, you’re done for.” The Indian conservation and forestry officials were fierce and effective, he said, and in recent years, the local wild elephant population had grown well. We learned that elephants roam the roads and routinely barge onto fields in Coorg, mainly at night, when they’re foraging. When people harassed them or made them think their babies were threatened, encounters could get ugly. The elephants killed between 15 and 20 Kodagu residents annually, according to Madhu.

“But what does a grower do when a group of elephants comes onto his coffee plantation?” I asked.

The best course was to stay out of their way, Maddhu said. They would soon move on. Trying to chase them away was usually disastrous; frightened, stampeding elephants could do tremendous damage. Left alone, they rarely lingered. And in Kodagu district, an area about a third the size of San Diego County, elephants have lots of alternative eating grounds. Somewhere between a half and two-thirds of the district land is protected tropical rainforest. The only humans who can enter it are forest rangers and hikers with guides.

On our second full day in Coorg, Steve and I got one of those permits and two guides (the minimum acceptable number.) One carried a gun in his backpack, and the other, a 34-year-old guy named Chengappa, had a lot of experience and an okay grasp of English. He seemed to know a lot about the local elephants, so I pelted him with my questions. Elephants in India no longer can be taken from the wild and put to work (as they were for millennia), he told us. But the animals at the Dubare camp (all but the babies) were former “rogues,” individuals who had killed a human or otherwise caused great destruction. Such elephants were tranquillized and brought to a center, where they were (essentially) broken in spirit, re-educated, and used for a weird range of activities — everything from getting all gussied up to march in the biggest annual festival in Mysore, to helping with special logging problems, to being taken into the forest to participate in elephant funerals.

He seemed to know a lot about the local elephants, so I pelted him with my questions. Elephants in India no longer can be taken from the wild and put to work (as they were for millennia), he told us. But the animals at the Dubare camp (all but the babies) were former “rogues,” individuals who had killed a human or otherwise caused great destruction. Such elephants were tranquillized and brought to a center, where they were (essentially) broken in spirit, re-educated, and used for a weird range of activities — everything from getting all gussied up to march in the biggest annual festival in Mysore, to helping with special logging problems, to being taken into the forest to participate in elephant funerals.

Cheng said in his 8 years of working for the forestry department, he’d never heard of a guide or trekker being hurt by an elephant, but it wasn’t unimaginable, and the forest harbored other scary creatures — the Indian gaur (a buffalo-like animal similar in ferocity to the African Cape buffalo), pit vipers, tigers, leopards, jaguars. The only mammal I saw was a civet, swinging through a giant tree, but the ground was dense with spider webs, some of which built complex tube structures. This guy was about a half-inch tall. The forest also teemed with little leeches…

This guy was about a half-inch tall. The forest also teemed with little leeches… like this one, about an inch in length.

like this one, about an inch in length.

To protect ourselves from them, we all tucked our pants inside our socks, but several still fell from the trees and tried to attach themselves to my bare arms. Each time this happened I knocked them off with a yelp and a shudder.

We covered an eight and a half mile loop that included more tough climbs and descents than Steve and I have done in a while. The terrain we moved through was so dense and varied it felt Jurassic.

Sometimes we edged ourselves downward by stepping into little ledges created by the elephant’s footprints, dodging fresh elephant poop. Even though we saw no actual elephants, it warmed my heart to know they still claimed such a breathtaking sanctuary as their home.

Sometimes we edged ourselves downward by stepping into little ledges created by the elephant’s footprints, dodging fresh elephant poop. Even though we saw no actual elephants, it warmed my heart to know they still claimed such a breathtaking sanctuary as their home.

Besides sharing that space for a few hours, Steve acquired another souvenir from the hike. When he got back to Sheila’s and took off his shoes and socks, this is what he found:

All the leeches had fallen off, as Cheng said they would. We found them (fat and happy) inside Steve’s shoes, and we discarded them. Strangely enough, not one got to me. Another mystery of nature (or maybe sock mechanics).