Our final stop on Shikoku was Matsuyama, the island’s biggest city. We only had a day and a half, but we made it to three of the city’s most highly praised sights:

One was Matsuyama Castle, one of the largest and best-preserved fortified dwellings in all Japan. We went on a rainy afternoon when it was easy to conjure up the samurai ghosts. (Good English translations of the displays helped.)

It was even more impressive than Kochi’s well-preserved castle, which we visited while there. The weather was better in Kochi, so when we climbed to the top-most level of the tower, we could better appreciate the great views.

The second major site we visited in Matsuyama was Ishite-Ji, one of Matsuyama’s many Buddhist temples. There I was disappointed to find the main building under renovation. But the grounds were wonderfully atmospheric…

We also crept into a a weird meditation tunnel chiseled into the rocky stone that abuts the temple complex.

Most exciting to me was catching sight of several arriving pilgrims. The Shikoku Pilgrimage is kind of a big deal on the island. Religious devotees try to follow a circuit that includes 88 temples; reportedly it takes 2-3 months to do it on foot. While achieving this would give one great bragging rights, it’s not on my bucket list. Still I was happy to glimpse some of those who were called by it.

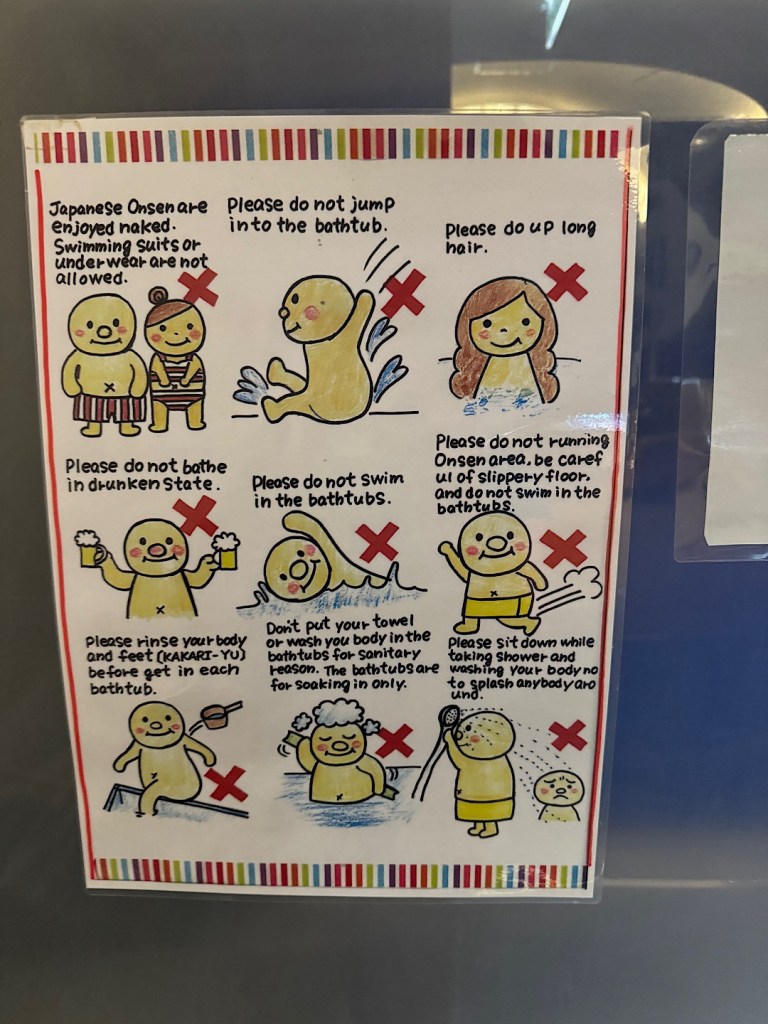

The third Big Attraction in town is Dogo Onsen (onsen are hot springs and the bathing facilities around them). This one is said to be the oldest in Japan (3000 years old? So they say.) You have to pay an admission fee to enter the 130-year-old main resort building (Dogo Onsen Honkan). Because we had failed to bring towels and robes with us, we paid about $27 for the two of us to enter, bathe, and get not only towels and robes but also tea and cookies.

I should explain here that Steve’s not a huge fan of Japanese bathing, which we have done many times over the years. In 1979 we visited a town where the streets were filled with freshly scrubbed people strolling around in just robes and sandals. In 1982 we went to an onsen in the north where men and women soaked together, au natural, in lovely outdoor pools. On this trip, we used the communal baths at two places, both of which reminded Steve he finds nothing appealing about sitting in hot water with a bunch of other naked men. I’m more of a fan of the whole experience. I learned the rules of Japanese bathing way back on my first trip to Japan.

Steeping myself in very hot pools alongside other naked women is so wildly different from anything back home, I find the rituals interesting — and the hot-water dips relaxing.

At Dogo Onsen, Steve was a good sport and accompanied me into the spa (though we couldn’t soak together. In most places, it’s a sex-segregated activity.)

We enjoyed all three of these activities, but two other things happened that seemed more wonderfully, quintessentially Japanese. We stumbled on one while walking to the onsen through one of the town’s pleasant covered malls. An odd sight caught my eye:

It seemed the juice was squeezed from varieties of fruit hybridized and grown in Ehime Prefecture. We recognized a few like blood orange. But most were alien: Seminole juice? Buntan?

We picked out three to share; the total came to $5. None of them tasted exactly like the orange juice or tangerine juice or grapefruit juice we know from home.They weren’t blends of those, but squeezed from wholly different fruit, clearly related but different. As we walked in, customers of all ages were streaming in, happy to be trying something new, as people here tend to be.

Our other striking experience came on our final night on Shikoku. We’d wanted to eat somewhere good but close to our hotel; Google Maps showed us at least a dozen candidates within a 5-minute radius. We selected a highly rated one which looked to be just a half block down a little street almost directly across from where we were staying. We followed Google’s directions and were baffled to find a dark alley containing no sign of any commercial establishment (even though Google said it should be open.) We walked in various directions, increasingly frustrated. Steve was certain Google was simply wrong. But I pushed for one more careful walk through the alley before we caved and went to the nearest burger joint. And there it was!

We climbed an unpromising set of stairs…

…pushed open the door, and were greeted with a cry of welcome from the solitary figure working behind the counter. The room was lovely — sleekly elegant with lots of warm wood tones. Music played softly in the background. The only other person in the place was a single woman nursing a drink at the bar.

Steve and I wound up splurging on the Matsuyama Special. But what a fabulous range of deliciousness it included.

Then she presented us with a pretty paper bag containing Japanese snacks and some candy. Her gift to us for coming to dinner.

by reporting on train travel in the UK and Europe — time tables for the major routes, how the system worked in each country, how to buy tickets, and so on. Pretty soon you had expanded to cover the whole world (as far as I can tell). Thanks to you, I’ve been able to plan train trips that took Steve and me from Singapore up the Malay peninsula (2016); from

by reporting on train travel in the UK and Europe — time tables for the major routes, how the system worked in each country, how to buy tickets, and so on. Pretty soon you had expanded to cover the whole world (as far as I can tell). Thanks to you, I’ve been able to plan train trips that took Steve and me from Singapore up the Malay peninsula (2016); from

Its comfortable reclining seats, clean toilets, and functioning power made that ride a pleasure. I knew that to continue on from Surabaya to Ketapang on Java’s eastern tip our only option was an “Ekonomi-class” line but those trains were “perfectly safe and comfortable,” you assured us readers.

Its comfortable reclining seats, clean toilets, and functioning power made that ride a pleasure. I knew that to continue on from Surabaya to Ketapang on Java’s eastern tip our only option was an “Ekonomi-class” line but those trains were “perfectly safe and comfortable,” you assured us readers.

The bench seats on the one we took were plain, and it was all but impossible to avoid playing kneesies with the plump young woman who faced me for the first four and a half hours of the ride. But any train that posts a photo of its conductor has to make you feel you’re in competent hands.

The bench seats on the one we took were plain, and it was all but impossible to avoid playing kneesies with the plump young woman who faced me for the first four and a half hours of the ride. But any train that posts a photo of its conductor has to make you feel you’re in competent hands. We left Surabaya just three seconds after 5:30 a.m. and pulled into Ketapang six hours and 59 minutes later — a minute ahead of schedule.

We left Surabaya just three seconds after 5:30 a.m. and pulled into Ketapang six hours and 59 minutes later — a minute ahead of schedule.

In 1945 it also was the setting for a key event in the birth of Indonesia as an independent country. So when you declared, “Even if you’re on a budget, splurge here,” I complied. What a bargain splurge it turned out to be: $89 a day for a lovely suite in a setting that enticed us to abandon our normal hyper-driven sightseeing and spend a whole day chilling out.

In 1945 it also was the setting for a key event in the birth of Indonesia as an independent country. So when you declared, “Even if you’re on a budget, splurge here,” I complied. What a bargain splurge it turned out to be: $89 a day for a lovely suite in a setting that enticed us to abandon our normal hyper-driven sightseeing and spend a whole day chilling out.

On December 20, five days after Steve and I returned from our nine-week Asian adventure, the New York Times published an article by its Frugal Traveler entitled “

On December 20, five days after Steve and I returned from our nine-week Asian adventure, the New York Times published an article by its Frugal Traveler entitled “ The Pollution — I knew the air in India might be bad, but I was unprepared for the depths of its wretchedness. In the course of our trip, I discovered that the weather app on my iPhone includes an “air quality index.” Since we’ve gotten back, I’ve been checking it and have learned that San Diego’s air typically falls in the 20-50 range (“Good”), occasionally dipping up to moderate pollution levels. When we arrived in Bengal, however, the index number was about 150 (“Unhealthy for sensitive groups”), and it got worse city by city after that, through “Unhealthy” then “Very Unhealthy” then “Hazardous” (in the 300-500 range). By the time we hit Jaipur in Rajasthan, it was over 500, literally off the chart. (“Don’t Even Think about What This is Doing to Your Lungs!!!”) I started coughing maybe a week after our arrival October 15 and still haven’t totally stopped (though I feel 99% better).

The Pollution — I knew the air in India might be bad, but I was unprepared for the depths of its wretchedness. In the course of our trip, I discovered that the weather app on my iPhone includes an “air quality index.” Since we’ve gotten back, I’ve been checking it and have learned that San Diego’s air typically falls in the 20-50 range (“Good”), occasionally dipping up to moderate pollution levels. When we arrived in Bengal, however, the index number was about 150 (“Unhealthy for sensitive groups”), and it got worse city by city after that, through “Unhealthy” then “Very Unhealthy” then “Hazardous” (in the 300-500 range). By the time we hit Jaipur in Rajasthan, it was over 500, literally off the chart. (“Don’t Even Think about What This is Doing to Your Lungs!!!”) I started coughing maybe a week after our arrival October 15 and still haven’t totally stopped (though I feel 99% better). Beyond the physical ill effects, the environmental despoliation was depressing. The air was foul not just here and there but every single place throughout the north and at least down to Mumbai (Bombay). Kerala in the far south was slightly better, though hardly pristine. Seen through clean air, much of the Indian landscape would be beautiful. Its absence is heartbreaking.

Beyond the physical ill effects, the environmental despoliation was depressing. The air was foul not just here and there but every single place throughout the north and at least down to Mumbai (Bombay). Kerala in the far south was slightly better, though hardly pristine. Seen through clean air, much of the Indian landscape would be beautiful. Its absence is heartbreaking.

Throughout the seven weeks we traveled in India, I thought more than once about the parable of the blind men and the elephant. It recounts what happened when a group of blind men investigated the strange new creature they had heard about. Each man touched a different part of the beast, and each formed a clear idea of what it must look like. The guy who felt the trunk said the elephant was like a snake. The one who touched its side said that was nonsense; elephants instead resembled walls. The man who stroked its ear concluded they’re like fans, and so on. Each was so convinced the others were wrong they eventually came to blows.

Throughout the seven weeks we traveled in India, I thought more than once about the parable of the blind men and the elephant. It recounts what happened when a group of blind men investigated the strange new creature they had heard about. Each man touched a different part of the beast, and each formed a clear idea of what it must look like. The guy who felt the trunk said the elephant was like a snake. The one who touched its side said that was nonsense; elephants instead resembled walls. The man who stroked its ear concluded they’re like fans, and so on. Each was so convinced the others were wrong they eventually came to blows.

One bad thing about Kerala is its heat and humidity, but in Peter’s big canoe, propelled by a local villager armed with a long pole, a light breeze cooled us. Crossing a broad channel, we sheltered under a big umbrella…

One bad thing about Kerala is its heat and humidity, but in Peter’s big canoe, propelled by a local villager armed with a long pole, a light breeze cooled us. Crossing a broad channel, we sheltered under a big umbrella… …then slipped under a low gate…

…then slipped under a low gate… …into a series of narrow canals shaded by coconut palms, mahogany, and other huge tropical trees.

…into a series of narrow canals shaded by coconut palms, mahogany, and other huge tropical trees. For a long time, Peter stopped talking, and we glided through the passages hearing only the birdsong and the swish of the water moving over the hull.

For a long time, Peter stopped talking, and we glided through the passages hearing only the birdsong and the swish of the water moving over the hull. …drink their water…

…drink their water… and taste their custardy insides.

and taste their custardy insides. We continued on to a tiny island and met the man who first settled it and now lives there with his relatives and a few other families.

We continued on to a tiny island and met the man who first settled it and now lives there with his relatives and a few other families. We ate a delicious lunch prepared by two of the women in the family…

We ate a delicious lunch prepared by two of the women in the family… …and learned how to spin twine out of coconut fiber.

…and learned how to spin twine out of coconut fiber. That’s Peter. By the time we got back to our hotel, he felt like an old friend.

That’s Peter. By the time we got back to our hotel, he felt like an old friend.

The heart of old Cochin is 500 years old, and you can sense that.

The heart of old Cochin is 500 years old, and you can sense that. Here’s what the stage looked like when we walked in.

Here’s what the stage looked like when we walked in. The make-up application had just begun.

The make-up application had just begun. It continued over the course of the next hour.

It continued over the course of the next hour. Then we listened to a short lecture about the performance elements. Actors don’t speak but rather communicate meaning with highly stylized hand signs, facial expressions (like this one. I think it was revulsion)…

Then we listened to a short lecture about the performance elements. Actors don’t speak but rather communicate meaning with highly stylized hand signs, facial expressions (like this one. I think it was revulsion)… and eye movements. Kathalkali actors must train their eyeballs like athletes. I’ve never seen such amazing control over that body organ.

and eye movements. Kathalkali actors must train their eyeballs like athletes. I’ve never seen such amazing control over that body organ.

We didn’t go to Kodagu looking for elephants. We got interested in the area when a friend who has worked and traveled for pleasure in India told us Kodagu was a spice capital of south India, dense with gorgeous jungle. Then another friend put us in touch with an Indian friend who lives in Bangalore and owns two coffee plantations in Kodagu (also known as Coorg, the old British name). I emailed Sheila, asking if we might meet for a lunch, and in an amazing display of generosity, she invited us to stay in the guesthouse on one of her plantations. We made plans to spend three nights.

We didn’t go to Kodagu looking for elephants. We got interested in the area when a friend who has worked and traveled for pleasure in India told us Kodagu was a spice capital of south India, dense with gorgeous jungle. Then another friend put us in touch with an Indian friend who lives in Bangalore and owns two coffee plantations in Kodagu (also known as Coorg, the old British name). I emailed Sheila, asking if we might meet for a lunch, and in an amazing display of generosity, she invited us to stay in the guesthouse on one of her plantations. We made plans to spend three nights. In about 15 minutes, Steve and I made it aboard a boat and quickly reached the camp. In the hour and a half we were there, no person, no signs, no brochures told us anything about what the camp is and how it functions. Maybe the Indians thought it was irrelevant. Most folks didn’t come here for helpings of wildlife education: the draw was watching the residents get their morning bath.

In about 15 minutes, Steve and I made it aboard a boat and quickly reached the camp. In the hour and a half we were there, no person, no signs, no brochures told us anything about what the camp is and how it functions. Maybe the Indians thought it was irrelevant. Most folks didn’t come here for helpings of wildlife education: the draw was watching the residents get their morning bath.

then using that ancient Asian-elephant-control tool, the hook, to make them lay down in the water…

then using that ancient Asian-elephant-control tool, the hook, to make them lay down in the water… or stand patiently while their tusks were cleaned with a sand-paste rub.

or stand patiently while their tusks were cleaned with a sand-paste rub.

Poke this baby into the tender spot behind one of those big ears, and you can get a 10,000-pound beast to do what you want!

Poke this baby into the tender spot behind one of those big ears, and you can get a 10,000-pound beast to do what you want! It was hard to tell what the elephants thought.

It was hard to tell what the elephants thought. It didn’t look like they hated it. But was it pleasurable?

It didn’t look like they hated it. But was it pleasurable? …as when one wrapped his charge’s trunk around this young lady’s neck, in response to a photo request. But most of the guys ignored the crowd gaping at them and concentrated instead on scrubbing the tough hides.

…as when one wrapped his charge’s trunk around this young lady’s neck, in response to a photo request. But most of the guys ignored the crowd gaping at them and concentrated instead on scrubbing the tough hides. They reminded me of car-wash attendants, irritable because of the long line of customers awaiting service.

They reminded me of car-wash attendants, irritable because of the long line of customers awaiting service. I tried to communicate good will with my touch. I ran my fingers over a few tusks, the source of so much elephant suffering and death. Then I rejoined Steve, and we walked to the high ground, where we found workers wrapping up brown rice within handfuls of hay.

I tried to communicate good will with my touch. I ran my fingers over a few tusks, the source of so much elephant suffering and death. Then I rejoined Steve, and we walked to the high ground, where we found workers wrapping up brown rice within handfuls of hay.

It did look to me like they enjoyed getting the tasty packages.

It did look to me like they enjoyed getting the tasty packages. He seemed to know a lot about the local elephants, so I pelted him with my questions. Elephants in India no longer can be taken from the wild and put to work (as they were for millennia), he told us. But the animals at the Dubare camp (all but the babies) were former “rogues,” individuals who had killed a human or otherwise caused great destruction. Such elephants were tranquillized and brought to a center, where they were (essentially) broken in spirit, re-educated, and used for a weird range of activities — everything from getting all gussied up to march in the biggest annual festival in Mysore, to helping with special logging problems, to being taken into the forest to participate in elephant funerals.

He seemed to know a lot about the local elephants, so I pelted him with my questions. Elephants in India no longer can be taken from the wild and put to work (as they were for millennia), he told us. But the animals at the Dubare camp (all but the babies) were former “rogues,” individuals who had killed a human or otherwise caused great destruction. Such elephants were tranquillized and brought to a center, where they were (essentially) broken in spirit, re-educated, and used for a weird range of activities — everything from getting all gussied up to march in the biggest annual festival in Mysore, to helping with special logging problems, to being taken into the forest to participate in elephant funerals. This guy was about a half-inch tall. The forest also teemed with little leeches…

This guy was about a half-inch tall. The forest also teemed with little leeches… like this one, about an inch in length.

like this one, about an inch in length.

Sometimes we edged ourselves downward by stepping into little ledges created by the elephant’s footprints, dodging fresh elephant poop. Even though we saw no actual elephants, it warmed my heart to know they still claimed such a breathtaking sanctuary as their home.

Sometimes we edged ourselves downward by stepping into little ledges created by the elephant’s footprints, dodging fresh elephant poop. Even though we saw no actual elephants, it warmed my heart to know they still claimed such a breathtaking sanctuary as their home.

“But there are plenty of middle-class people in India now, aren’t there?” I interjected.

“But there are plenty of middle-class people in India now, aren’t there?” I interjected. Just north of it begins a series of neighborhoods renowned for their maze-like bazaars. As it turned out, it was too early for many of the shops to be open, but we did pass guys carrying big tubs of fish on their heads

Just north of it begins a series of neighborhoods renowned for their maze-like bazaars. As it turned out, it was too early for many of the shops to be open, but we did pass guys carrying big tubs of fish on their heads and others selling them from tarps on the sidewalk.

and others selling them from tarps on the sidewalk. We passed trucks of suffering and doomed chickens that made me (briefly) consider never eating chicken again.

We passed trucks of suffering and doomed chickens that made me (briefly) consider never eating chicken again. The old Crawford food market (the exterior of which still bears beautiful sculpture work done by Rudyard Kipling’s father)

The old Crawford food market (the exterior of which still bears beautiful sculpture work done by Rudyard Kipling’s father) was just coming to life, and within it, I spotted a booth carrying all manner of canned drinks, including our beloved Schweppes (in both Indian and foreign sizes.) Steve was ecstatic. He bought six (Indian) cans from this guy.

was just coming to life, and within it, I spotted a booth carrying all manner of canned drinks, including our beloved Schweppes (in both Indian and foreign sizes.) Steve was ecstatic. He bought six (Indian) cans from this guy.

Had we gotten there too late? Were dabba-wallahs as endangered as those Rajasthani camels? I felt a wave of disappointment.

Had we gotten there too late? Were dabba-wallahs as endangered as those Rajasthani camels? I felt a wave of disappointment. It was indeed a thick congregation of dabbah-wallahs, loading up their conveyances. I hadn’t immediately recognized them because they were using so many insulated bags instead of the traditional tin canisters. Some had dozens of the lunch bags piled up on wooden hand carts…

It was indeed a thick congregation of dabbah-wallahs, loading up their conveyances. I hadn’t immediately recognized them because they were using so many insulated bags instead of the traditional tin canisters. Some had dozens of the lunch bags piled up on wooden hand carts… …while others stood by bicycles hung with motley receptacles.

…while others stood by bicycles hung with motley receptacles.

The face of the modern dabba-wallah.

The face of the modern dabba-wallah.

We wound up there because a listing in the “Activities” section of the Lonely Planet’s Udaipur chapter raved about Shashi’s cooking classes. I emailed to see if we could join one and got a response saying the 5:30 pm Saturday (11/17) class had two openings. This was a stretch; on Saturday we had to set the alarm in Jodhpur for 6 am to catch a train. After that five-hour journey, our taxi got stuck in a giant traffic jam. But we didn’t want to miss the opportunity, so precisely at 5:30 pm we walked into a trim little kitchen on the upper floor of a building down the street from our hotel.

We wound up there because a listing in the “Activities” section of the Lonely Planet’s Udaipur chapter raved about Shashi’s cooking classes. I emailed to see if we could join one and got a response saying the 5:30 pm Saturday (11/17) class had two openings. This was a stretch; on Saturday we had to set the alarm in Jodhpur for 6 am to catch a train. After that five-hour journey, our taxi got stuck in a giant traffic jam. But we didn’t want to miss the opportunity, so precisely at 5:30 pm we walked into a trim little kitchen on the upper floor of a building down the street from our hotel. We deep-fried them, then gobbled them down, dipped in two kinds of chutney (coriander and mango) both of which Shashi showed us how to make.

We deep-fried them, then gobbled them down, dipped in two kinds of chutney (coriander and mango) both of which Shashi showed us how to make.

We made the magic sauce, then we used it to makes several dishes, including curried chickpeas….

We made the magic sauce, then we used it to makes several dishes, including curried chickpeas…. deep-fried cheese in a tomato-butter sauce, and a vegetable pulao.

deep-fried cheese in a tomato-butter sauce, and a vegetable pulao. As each dish was completed, Shashi stacked it on its predecessors,

As each dish was completed, Shashi stacked it on its predecessors, a teasing metal tower that grew more maddeningly tempting as the hours went by, and we grew more and more tired and hungry. But there was more to learn, and lots of joking and laughter to distract us as we toiled. We made chapatti dough; learned out to knead it and cook it on a skillet.

a teasing metal tower that grew more maddeningly tempting as the hours went by, and we grew more and more tired and hungry. But there was more to learn, and lots of joking and laughter to distract us as we toiled. We made chapatti dough; learned out to knead it and cook it on a skillet. Many hands make good chapatti.

Many hands make good chapatti.

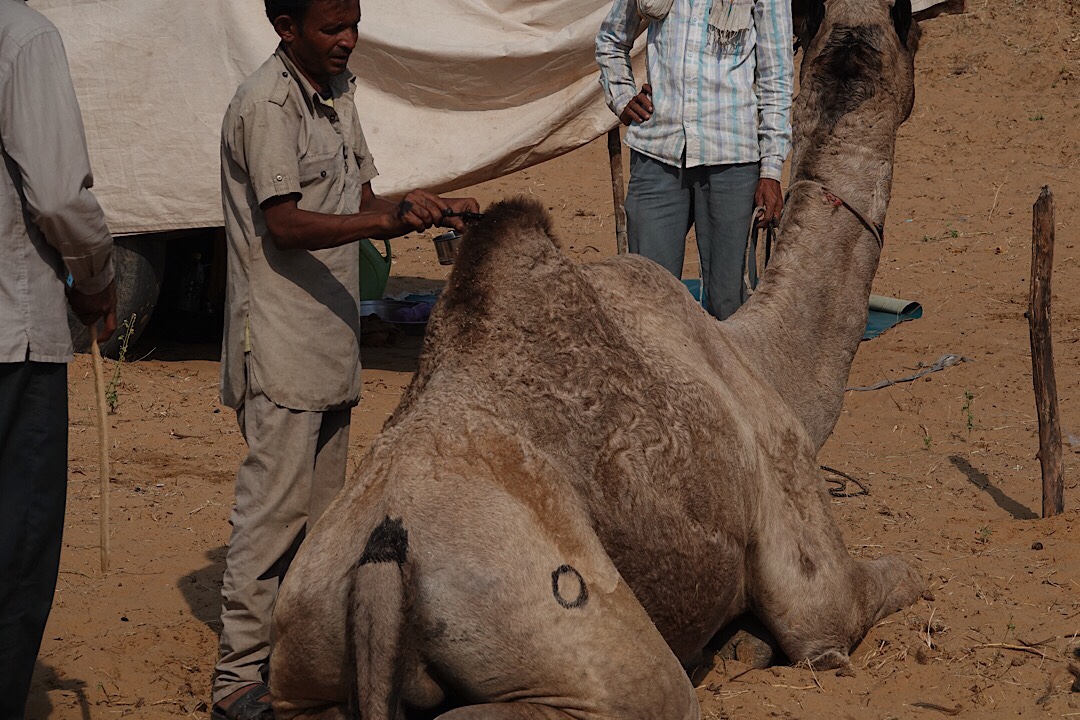

Somehow camels have become one of my favorite animals. I think this started in 2002 when I rode one in Luxor (Egypt), on the edge of the Sahara. It felt a bit like being on a gigantic rocking horse — fun and exhilarating and more comfortable than I expected.

Somehow camels have become one of my favorite animals. I think this started in 2002 when I rode one in Luxor (Egypt), on the edge of the Sahara. It felt a bit like being on a gigantic rocking horse — fun and exhilarating and more comfortable than I expected.

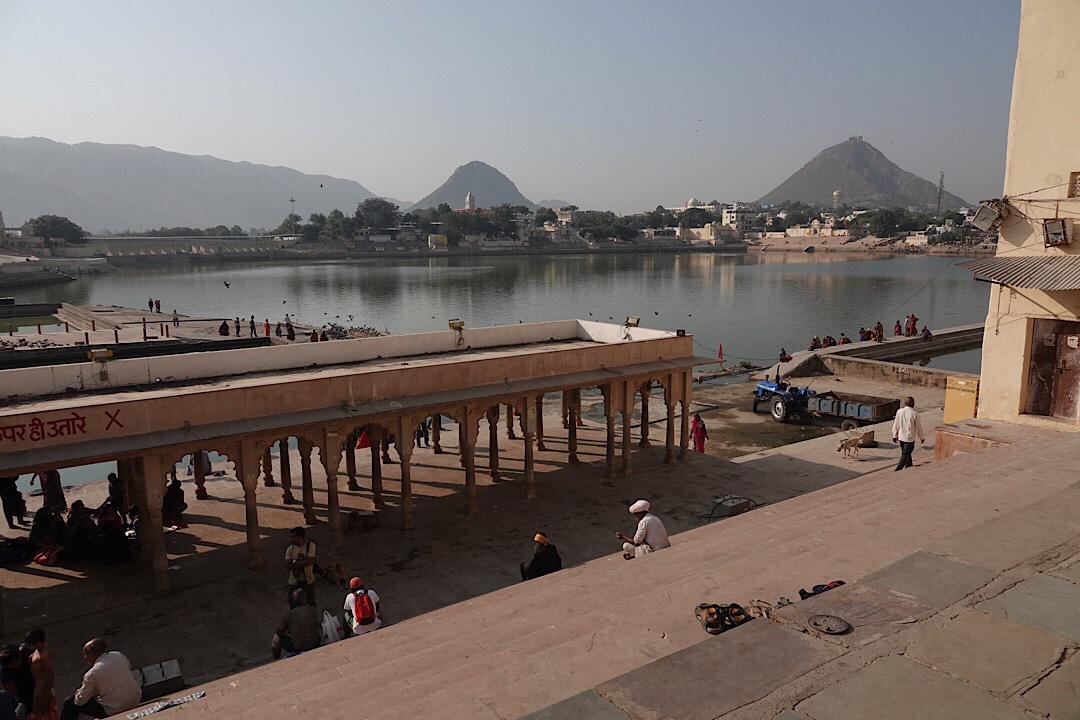

The devotees trickle in over a ten-day period, and they revel not only in the religious activities (praying, visiting various temples, smashing coconuts, launching lighted candles into the lake waters, etc.) but also shopping and enjoying Indian-style tourist attractions. They ride on camels or in carts pulled by them.

The devotees trickle in over a ten-day period, and they revel not only in the religious activities (praying, visiting various temples, smashing coconuts, launching lighted candles into the lake waters, etc.) but also shopping and enjoying Indian-style tourist attractions. They ride on camels or in carts pulled by them. They photograph snake charmers.

They photograph snake charmers. They ogle little girls walking on tightropes…

They ogle little girls walking on tightropes… or monkeys dressed up in little outfits.

or monkeys dressed up in little outfits. We spent hours wandering among the pilgrims. But I’d come for camels, not religious fanatics, so early on our first full day, we set out in the morning chill to find the hump-backed giants. (By noon, temperatures in Pushkar always climbed to the mid- to high-80s, but they plunged every night.) In the open grounds beyond the Brahma Temple, we found more camels assembled than I’ll ever see again in my life:

We spent hours wandering among the pilgrims. But I’d come for camels, not religious fanatics, so early on our first full day, we set out in the morning chill to find the hump-backed giants. (By noon, temperatures in Pushkar always climbed to the mid- to high-80s, but they plunged every night.) In the open grounds beyond the Brahma Temple, we found more camels assembled than I’ll ever see again in my life: thousands of them, most staked together in small groups or being groomed by their owners.

thousands of them, most staked together in small groups or being groomed by their owners.

The backward swastika has nothing to do with Nazis. It’s an ancient Hindu symbol. Herders paint their animals in various ways to jazz them up.

The backward swastika has nothing to do with Nazis. It’s an ancient Hindu symbol. Herders paint their animals in various ways to jazz them up.

From the humans’ body language, we sometimes identified negotiations in progress. From the camels’, it appeared that some were bored…

From the humans’ body language, we sometimes identified negotiations in progress. From the camels’, it appeared that some were bored… But some were curious.

But some were curious. Overwall the scene felt surprisingly low-key, and we returned on our final day to see if the pace had accelerated.

Overwall the scene felt surprisingly low-key, and we returned on our final day to see if the pace had accelerated.

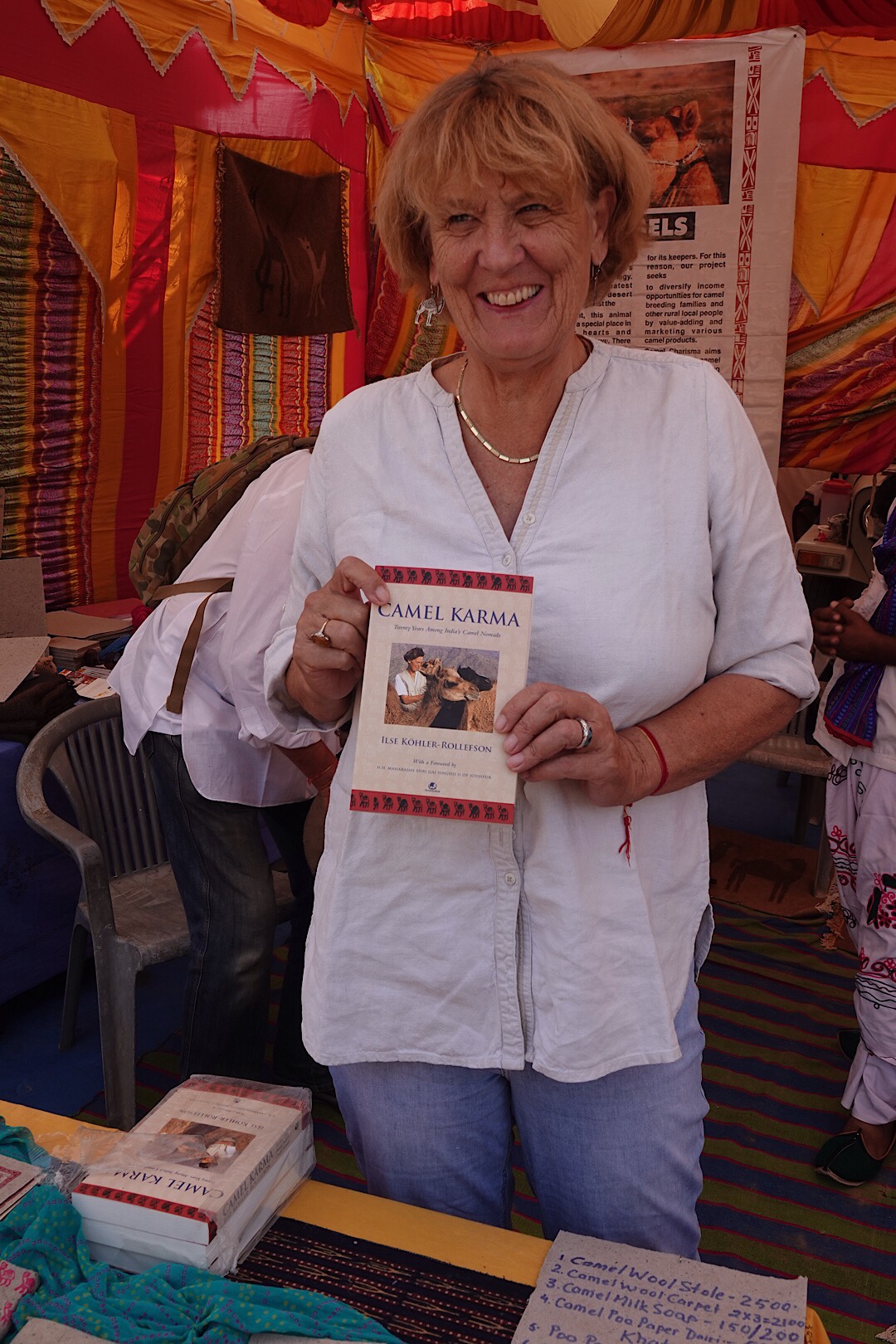

A talk blonde older woman in the back of the booth joined our conversation. She was a German anthropologist named Ilse Kohler-Rollefson who’d spent 20 years living among the camel nomads (and almost as amazingly, had lived for several years in San Diego and taught at San Diego State). She and her colleague explained that the NGO had helped start the first camel dairy in India. They were also lobbying for protection of traditional grazing grounds. The aim was to find ways for the herders to continue earning enough to survive.

A talk blonde older woman in the back of the booth joined our conversation. She was a German anthropologist named Ilse Kohler-Rollefson who’d spent 20 years living among the camel nomads (and almost as amazingly, had lived for several years in San Diego and taught at San Diego State). She and her colleague explained that the NGO had helped start the first camel dairy in India. They were also lobbying for protection of traditional grazing grounds. The aim was to find ways for the herders to continue earning enough to survive. We ran into Ilse too as she was buying an ice cream bar, and she told us that someone had delivered a rousing speech at the municipal center.

We ran into Ilse too as she was buying an ice cream bar, and she told us that someone had delivered a rousing speech at the municipal center. like these…

like these… and these.

and these. We entered through this gate and saw ladies in their new finery making offerings to various gods.

We entered through this gate and saw ladies in their new finery making offerings to various gods. So many men and women and children were out to view the decorations and buy desserts, the honking of taxis and tuk-tuks made it hard to hear the Diwali music blaring over loudspeakers.

So many men and women and children were out to view the decorations and buy desserts, the honking of taxis and tuk-tuks made it hard to hear the Diwali music blaring over loudspeakers. like this street.

like this street. This was more the norm, though.

This was more the norm, though. The current maharajah, just 20, still lives in the palace at the heart of the city.

The current maharajah, just 20, still lives in the palace at the heart of the city.

That’s him, with the sword, surrounded by his grandmother, mom, and siblings.

That’s him, with the sword, surrounded by his grandmother, mom, and siblings. The palace is filled with interesting objects, such as this giant silver vessel. One of the maharajahs had it filled with water from the Ganges, for him to drink on a trip to London. (Note that Steve prefers to travel lighter.)

The palace is filled with interesting objects, such as this giant silver vessel. One of the maharajahs had it filled with water from the Ganges, for him to drink on a trip to London. (Note that Steve prefers to travel lighter.)

You can ride up the hill to it on an elephant.

You can ride up the hill to it on an elephant.

The spikes in the door were supposed to deter war elephants from battering in the gate.

The spikes in the door were supposed to deter war elephants from battering in the gate. One view of the so-called Pleasure Room in the palace within the fort.

One view of the so-called Pleasure Room in the palace within the fort. The ceiling in one of the maharajah’s bedrooms.

The ceiling in one of the maharajah’s bedrooms. The view of Jodhpur’s Mehrangarh Fort at night, from the little haveli where we stayed.

The view of Jodhpur’s Mehrangarh Fort at night, from the little haveli where we stayed. Now I know the secret to seeing a tiger in Ranthambore National Park. Go in May or June, the peak of the dry season. Many of the trees in the park lose their leaves; streams dry up; waterholes shrink. With the undergrowth reduced and the tigers’ drinking sources limited, 90% of safari-goers encounter the animal superstars. The only problem: temperatures at this time of year typically are 110 to 120 degrees.

Now I know the secret to seeing a tiger in Ranthambore National Park. Go in May or June, the peak of the dry season. Many of the trees in the park lose their leaves; streams dry up; waterholes shrink. With the undergrowth reduced and the tigers’ drinking sources limited, 90% of safari-goers encounter the animal superstars. The only problem: temperatures at this time of year typically are 110 to 120 degrees. Our crew that morning, minus the guide, who took this photo.

Our crew that morning, minus the guide, who took this photo. This was India, home to 1.2 billion humans, yet it felt like a less crowded place, say, a (smoggy) forest in Idaho after heavy rains that had made everything lush and green. At times the vegetation pressed in so close we had to duck to avoid being scratched in the face by branches. We passed marshland…

This was India, home to 1.2 billion humans, yet it felt like a less crowded place, say, a (smoggy) forest in Idaho after heavy rains that had made everything lush and green. At times the vegetation pressed in so close we had to duck to avoid being scratched in the face by branches. We passed marshland… …and stands of banyan trees that took our breath away.

…and stands of banyan trees that took our breath away. Here and there, we glimpsed the 1000-year-old fort that topped a distant cliff top. (Later we read that the wall surrounding it is almost 5 miles long.)

Here and there, we glimpsed the 1000-year-old fort that topped a distant cliff top. (Later we read that the wall surrounding it is almost 5 miles long.)

Spotted deer…

Spotted deer… Sambar deer…

Sambar deer… Nilgai (a type of Indian antelope).

Nilgai (a type of Indian antelope). Wild boar…

Wild boar… Crocodile.

Crocodile. A cormorant drying his wings in the sun.

A cormorant drying his wings in the sun. Owls snoozing in a tree hole.

Owls snoozing in a tree hole. So many peacock they reminded us of seagulls in San Diego.

So many peacock they reminded us of seagulls in San Diego. This guy is known as the dentist of the jungle. Guides told us that they all but climb into the tigers’ mouths, cleaning their teeth, a mutually beneficial service that the tigers tolerate.

This guy is known as the dentist of the jungle. Guides told us that they all but climb into the tigers’ mouths, cleaning their teeth, a mutually beneficial service that the tigers tolerate. We all but ignored all the other animals we passed. We searched one area after another. With the sun getting closer to the horizon, we waited on a high ridge overlooking a canyon; listened to the birds. Saw no tigers.

We all but ignored all the other animals we passed. We searched one area after another. With the sun getting closer to the horizon, we waited on a high ridge overlooking a canyon; listened to the birds. Saw no tigers.

So now I know a second way to see a tiger in India: get lucky.

So now I know a second way to see a tiger in India: get lucky.