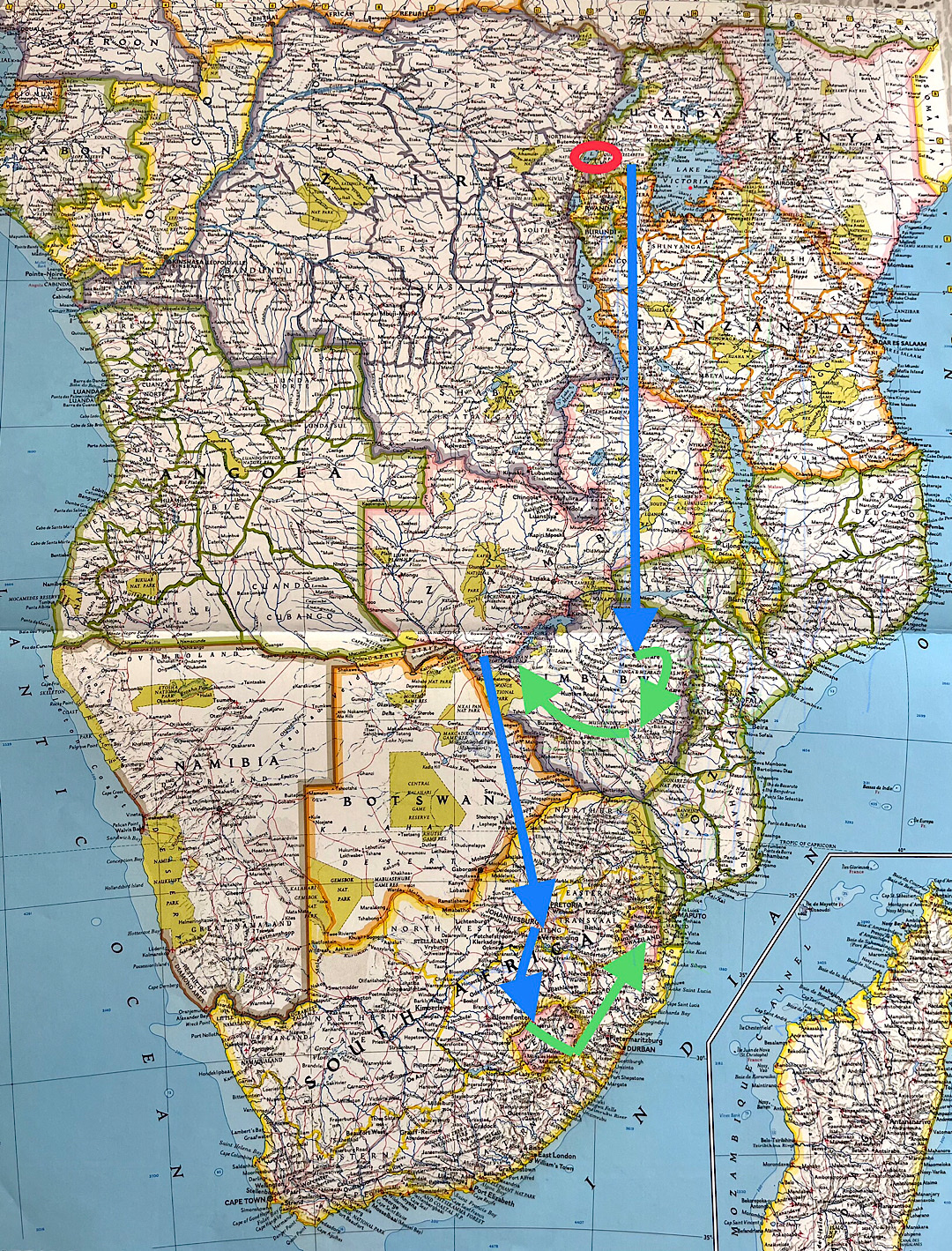

Rwandan roads are at least as good as those in the US, so I’m starting this post from the third row of seats in our 10-passenger van as we drive the two final hours to Kigali, the Rwandan capital. We crossed the border with Uganda a few minutes ago. Writing on the Ugandan byways, which range from good (occasionally) to abysmal (far too common), is pretty much impossible, given the jouncing. Off the road, our three and a half days in Uganda were so packed I couldn’t find a spare minute to get on my iPad when the sun was up. By the time it set, I’d run out of gas.

But I can summarize what we did.

We slogged out of Kampala through mind-bending traffic…

…then moved westward across the country to finally struggle up the broken dirt roads that lead to the village of Nyakagyesi. The trip ate up ten and a half hours — pretty much all of Monday.

Wednesday we devoted to meeting with the grandmother groups and their members who are receiving micro loans funded by Women’s Empowerment, the San Diego organization for which Steve and I serve as liaisons.

Thursday we toured the first primary school built by the Nyaka Foundation, its beautiful secondary school, and its health center, then we met with yet another set of grandmothers, these specializing in making jewelry, baskets, and other handicrafts.

After that we drove a couple of hours to Buhoma, where you can catch glimpses of the mountains on the other side of the border in Congo. Buhoma is a base for gorilla trekking, but everyone in our group had already done that (Jose and Mari two weeks ago; Steve and I in 2013.) Instead we paid a quick but fun visit to the office of a non-profit organization founded and run (by a woman I know in San Diego) to help the desperately poor local Batwa community.

The setting for all these activities has been a landscape that’s among the most beautiful on earth. A dozen shades of vibrant green, the land is all rugged mountains intermixed with verdant valleys and reddish soil so rich it produces almost every crop you can think of.

This morning an unexpected treat was when our drive to the Rwandan border took us over an 8000-foot pass in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest (today in fact penetrated by a fairly smooth dirt road.) This forest, home not just to mountain gorillas but also forest elephants, is 100 million years old. Because it didn’t freeze during the last Ice Age, it harbors fantastic biological diversity. We didn’t see any forest elephants on our passage but Deus, our driver, pointed out fresh deposits of their droppings on the road.

This was our fourth visit to Uganda, and another landscape, an invisible one, has also been coming into focus over the past ten years. It’s the network of relationships we’ve acquired. Some are with people we’ve come to love, like Jennifer Nantale, head of the whole Nyaka organization in Uganda and one of the smartest, toughest women I’ve ever met.

Or Sam Mugisha, the remarkable guy who in his youth jumped at a chance to travel to Japan, became fluent in Japanese, and returned home to start a travel business catering to visitors speaking that language. (He’s also been the outfitter for all our WE trips.)

Dozens upon dozens of encounters with various individuals have been more fleeting but still vivid. Some fade quickly, but they’re still part of the tapestry composed of all the warm, kind, hard-working people we’ve gotten to know here. The impression made by others remains sharp for longer, like Norah, whom we met her early Thursday afternoon.

Norah is a 72 widow who’s currently raising four grandchildren ranging in age from 12 to 4. She greeted us with a warm smile and explained that she joined the Kyepatiko granny group four years ago. Now she’s the chairperson. Over the years she’s gotten two loans from the group, the most recent one for 500,000 shillings (about $133). She combined that money with the 3 million shillings she had saved from her coffee crop and used the money to buy a cow and calf. When the calf was a baby, Norah was getting 5 liters of milk a day that she could sell for about 37 cents a liter. But now that the calf has grown, it consumes all its mother’s milk. Still, she had bred the cow about a month before our visit, and she was hoping to have a birth in about 8 months. She would then sell one of the calves.

Norah has a warm and confident presence, and she led us to the back of her substantial house to the clean and well-organized enclosure she has built for her cow and calf.

Besides her fledgling dairy business, Norah has also built up an apiary; today it houses 50 beehives. We couldn’t visit it because the bees would sting us during the day. (Norah and her family collect their honey at night when the insects are sleeping.) It’s a good business. The grandmother can charge about $68 for 5 liters of honey. It adds up to more than $500 over the course of a year. Still Norah said she wants to develop the market further.

The path to the apiary passed through healthy coffee trees laden with berries. And Norah also seemed proud of her field of emerald spears of elephant grass. She harvests it to feed to the dairy animals (which can’t just wander around, munching other people’s crops.)

Later, we watched Norah direct the grandmother group meeting. She commands attention with ease. Reflecting on our meeting with her at dinner a few nights later, Jose and Mari and Steve and I agreed she was hard to forget. “If she were in the US, she’s be the CEO at some big corporation,” someone said.

But I have to confess: my attention is drifting away from all that. It’s now Saturday morning and in a few minutes Steve and I will board our flight to Harare. Compared to the cozy familiarity of Uganda, Zimbabwe is terra incognito.

That’s what Steve and I will be doing Friday morning (9/15): buckling up as we take off on perhaps our most ambitious adventure.

That’s what Steve and I will be doing Friday morning (9/15): buckling up as we take off on perhaps our most ambitious adventure.

The news was discouraging when we landed on Rinca Island Tuesday afternoon. No one had spotted any Komodo dragons that entire day — nor the day before. I tried to resign myself to the same fate. When you seek rare animals in the wild, it’s not like buying a movie ticket. You’re not guaranteed a show. But we lucked out.

The news was discouraging when we landed on Rinca Island Tuesday afternoon. No one had spotted any Komodo dragons that entire day — nor the day before. I tried to resign myself to the same fate. When you seek rare animals in the wild, it’s not like buying a movie ticket. You’re not guaranteed a show. But we lucked out.

Another score! The ranger asked for Steve’s phone and recorded the temporary occupant: a male whose big belly testified to recent consumption of a meaty feast. Now he was digesting in the cool comfort of the man-made shelter.

Another score! The ranger asked for Steve’s phone and recorded the temporary occupant: a male whose big belly testified to recent consumption of a meaty feast. Now he was digesting in the cool comfort of the man-made shelter.

This was breakfast the second morning.

This was breakfast the second morning. The view from near the top, taking in three different-colored beaches (black, white, and pink) is so famous it’s on Indonesia’s 50,000-rupiah bank note. Indonesian tour groups pressed for time will often choose to visit it and skip the Komodo dragons, according to Robert.

The view from near the top, taking in three different-colored beaches (black, white, and pink) is so famous it’s on Indonesia’s 50,000-rupiah bank note. Indonesian tour groups pressed for time will often choose to visit it and skip the Komodo dragons, according to Robert.

This time our park ranger, Dula, took my iPhone and shot the wonderful video footage I will try to incorporate here. I hope it’s viewable on the blog; part terrifying, part comic, it’s documentary evidence of one of the most unforgettable strolls of my life.

This time our park ranger, Dula, took my iPhone and shot the wonderful video footage I will try to incorporate here. I hope it’s viewable on the blog; part terrifying, part comic, it’s documentary evidence of one of the most unforgettable strolls of my life. We didn’t succeed at seeing all of it. The wind blew hard for a few hours on our final morning, whipping up white caps that drove the local manta rays and sea turtles to deeper water. But we did manage to snorkel three times in calm water, and each outing delighted me. The sea was clear and warm, and I felt as close as I will ever get to flight, gliding effortlessly over the landscape of coral and anemones and rocks, in the company of neon-colored fish, many dressed up in astonishing patterns. At times we sailed by rivers of fish; into clouds of them. Once I started to laugh out loud at the concentrated beauty but was quickly reminded that’s not a great idea when you’re breathing through a snorkel.

We didn’t succeed at seeing all of it. The wind blew hard for a few hours on our final morning, whipping up white caps that drove the local manta rays and sea turtles to deeper water. But we did manage to snorkel three times in calm water, and each outing delighted me. The sea was clear and warm, and I felt as close as I will ever get to flight, gliding effortlessly over the landscape of coral and anemones and rocks, in the company of neon-colored fish, many dressed up in astonishing patterns. At times we sailed by rivers of fish; into clouds of them. Once I started to laugh out loud at the concentrated beauty but was quickly reminded that’s not a great idea when you’re breathing through a snorkel. We watched the molten tangerine sliver of sun shrink to a dot and disappear and the color begins to drain from the sky. Several long moments passed, but enough of a glow still remained that I could make out the strange thing that began to occur — a stream of tiny black objects rising out of the mangroves like cinders flowing up from a campfire and dispersing.

We watched the molten tangerine sliver of sun shrink to a dot and disappear and the color begins to drain from the sky. Several long moments passed, but enough of a glow still remained that I could make out the strange thing that began to occur — a stream of tiny black objects rising out of the mangroves like cinders flowing up from a campfire and dispersing. The stream thickened and grew; that’s when I cried out. These were fruit bats, a vast horde of them, ranging out by the millions to hunt insects in the night.

The stream thickened and grew; that’s when I cried out. These were fruit bats, a vast horde of them, ranging out by the millions to hunt insects in the night.

I did not come to Indonesia to do road trips. But now that I’ve done half of one, I can say at least they’re educational. If like Dorothy, you want visceral assurance you are NOT in Kansas, a drive through parts of Sumatra delivers. Our experience Sunday afternoon also solved a mystery for me, namely I had been unable to imagine how it could take four hours to go 65 miles in a nicely maintained Toyota SUV. Now I know.

I did not come to Indonesia to do road trips. But now that I’ve done half of one, I can say at least they’re educational. If like Dorothy, you want visceral assurance you are NOT in Kansas, a drive through parts of Sumatra delivers. Our experience Sunday afternoon also solved a mystery for me, namely I had been unable to imagine how it could take four hours to go 65 miles in a nicely maintained Toyota SUV. Now I know.

When you’re all barreling over two narrow lanes, driving becomes vastly more freestyle than anything you ever see in the US or Europe, People thread their way up the wrong side of the road. Many folks favor straddling the faded middle divider line, probably to enhance their readiness for passing. Not passing is NOT an option. You simply must get around all the barely motorized vehicles carrying improbable loads.

When you’re all barreling over two narrow lanes, driving becomes vastly more freestyle than anything you ever see in the US or Europe, People thread their way up the wrong side of the road. Many folks favor straddling the faded middle divider line, probably to enhance their readiness for passing. Not passing is NOT an option. You simply must get around all the barely motorized vehicles carrying improbable loads.

All this chaos feels remarkably dangerous, and we saw direct confirmation that, yes, it is. We passed the large truck whose crash had delayed Hari. Someone had somehow got it upright again, but it was still stuck by the side of the road. Further along, we whizzed by a demolished motorbike whose driver was still struggling to get up from under it.

All this chaos feels remarkably dangerous, and we saw direct confirmation that, yes, it is. We passed the large truck whose crash had delayed Hari. Someone had somehow got it upright again, but it was still stuck by the side of the road. Further along, we whizzed by a demolished motorbike whose driver was still struggling to get up from under it.

My head swiveled, too, at all the broad rivers we crossed, most the color of coffee with cream.

My head swiveled, too, at all the broad rivers we crossed, most the color of coffee with cream. Around 5:35 the light was starting to dim and I cringed at the thought of it vanishing altogether as we rattled along for another 75 minutes. But then Hari piped up that we were almost at our destination! Indeed we bounced over dirt road for only a few minutes, entered a jungly stretch of road, and then stopped at a sign for the lodge next to a dirt path leading into a thicket of green. The sun still hadn’t set when we greeted the owner.

Around 5:35 the light was starting to dim and I cringed at the thought of it vanishing altogether as we rattled along for another 75 minutes. But then Hari piped up that we were almost at our destination! Indeed we bounced over dirt road for only a few minutes, entered a jungly stretch of road, and then stopped at a sign for the lodge next to a dirt path leading into a thicket of green. The sun still hadn’t set when we greeted the owner.

He gave us boarding passes that let us go first through the jetway,

He gave us boarding passes that let us go first through the jetway, so we had tons of room, sitting in the first row. I Stayed in a perfect Down position when the flight attendant gave her speech,

so we had tons of room, sitting in the first row. I Stayed in a perfect Down position when the flight attendant gave her speech,  and although I got a little nervous during the take-off (and later, the landing), my p/M gave me the Lap command and let me look out the window. I found the sights out the window intriguing, if slightly creepy.

and although I got a little nervous during the take-off (and later, the landing), my p/M gave me the Lap command and let me look out the window. I found the sights out the window intriguing, if slightly creepy. Just as often, I napped.

Just as often, I napped.

Frankly, I’m not a fan.

Frankly, I’m not a fan. And pretty soon the sun was shining again.

And pretty soon the sun was shining again.

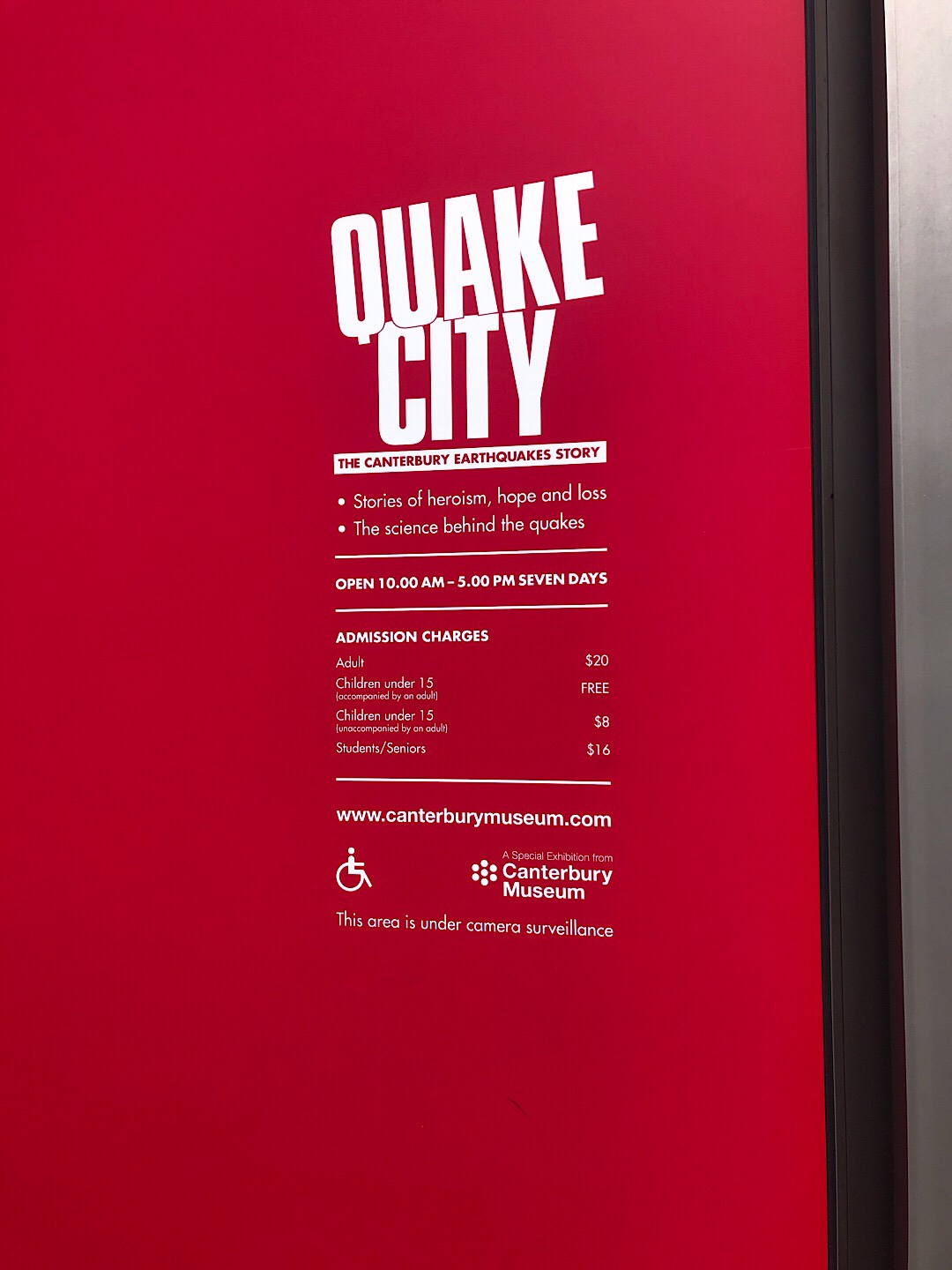

I knew two bad earthquakes hit Christchurch in 2010 and 2011, but they didn’t become real for me until the night Steve and I were eating dinner in Kaikoura. Looking out the window next to our table, Steve exclaimed, “Is that a bobcat?” The animal he was staring at seemed too small to be that, but it lacked a tail. “He lost it in the earthquake,” our waitress (the wife of the owner) told us. Her house in Christchurch had also collapsed, she added, and she and her husband had lost the five restaurants they owned. They’d recently moved to Kaikoura, trying to start over. This lady was a hearty, jokey sort of person, but the way her face subtly tightened when she talked of the disaster betrayed how overwhelming it had been. Watching her face, I struggled to keep mine composed.

I knew two bad earthquakes hit Christchurch in 2010 and 2011, but they didn’t become real for me until the night Steve and I were eating dinner in Kaikoura. Looking out the window next to our table, Steve exclaimed, “Is that a bobcat?” The animal he was staring at seemed too small to be that, but it lacked a tail. “He lost it in the earthquake,” our waitress (the wife of the owner) told us. Her house in Christchurch had also collapsed, she added, and she and her husband had lost the five restaurants they owned. They’d recently moved to Kaikoura, trying to start over. This lady was a hearty, jokey sort of person, but the way her face subtly tightened when she talked of the disaster betrayed how overwhelming it had been. Watching her face, I struggled to keep mine composed. One of the things that shocked me most was learning that the two earthquakes which all but destroyed the central city were far from the worst that’s expected for this region. The huge fault, the one capable of moving with a force of more than magnitude 8, runs up the east side of the southern Alps, just an hour or two outside Christchurch.

One of the things that shocked me most was learning that the two earthquakes which all but destroyed the central city were far from the worst that’s expected for this region. The huge fault, the one capable of moving with a force of more than magnitude 8, runs up the east side of the southern Alps, just an hour or two outside Christchurch.

But there are urban centers in America’s rust belt that look worse. And few cities anywhere have mounted the kind of makeover that’s underway here.

But there are urban centers in America’s rust belt that look worse. And few cities anywhere have mounted the kind of makeover that’s underway here.

There’s much more to come, including rebuilding the cathedral, finishing the zoomy convention center that’s supposed to start operating next year…

There’s much more to come, including rebuilding the cathedral, finishing the zoomy convention center that’s supposed to start operating next year… …and building a deluxe sports complex…

…and building a deluxe sports complex…

Artists have been commissioned to paint murals on the sides of newly revealed building sides…

Artists have been commissioned to paint murals on the sides of newly revealed building sides… … and create other works to fill the civic gaps.

… and create other works to fill the civic gaps.

Around noon Wednesday, we returned Car #3 and added up the total mileage covered with our three rentals. Steve safely piloted us a total of 2,124 miles. He says it felt like twice that long. The extra concentration required by the left-side driving on narrow roads never ceased to be tiring, although after three-plus weeks, it was far less foreign than when we started. We never regretted making this as much of a road trip as we did; the freedom it gave us was delicious. But we also were so happy we were able to shorten the driving portion, just a bit.

Around noon Wednesday, we returned Car #3 and added up the total mileage covered with our three rentals. Steve safely piloted us a total of 2,124 miles. He says it felt like twice that long. The extra concentration required by the left-side driving on narrow roads never ceased to be tiring, although after three-plus weeks, it was far less foreign than when we started. We never regretted making this as much of a road trip as we did; the freedom it gave us was delicious. But we also were so happy we were able to shorten the driving portion, just a bit.

optional pre-recorded guiding commentary, an open-air viewing car…

optional pre-recorded guiding commentary, an open-air viewing car…

But who would choose to look up at them with scenes like this outside the window?

But who would choose to look up at them with scenes like this outside the window?