Steve keeps referring to Puerto Rico as “America’s biggest colony” even though I know that’s politically incorrect (both literally and socially). But I’m used to him being provocative. What we agree on is how weird it felt to be in a place where all the residents are entitled to carry US passports, but everyone speaks Spanish, and the capital city looks like Havana would probably look had Cuba not been governed by brutal Communist dictators for the past 65 years.

For our visit, I brought along the article that appeared in the New York Times last month: “36 Hours in San Juan.” Steve and I actually had 52 hours, all of which we spent in the oldest part of this oldest European city in the Western Hemisphere. A vast metropolis surrounds the old town, but I know nothing about it, except that our ride from the airport felt like we were back in the US.

Judgments based on such limited exposure are bound to be pathetic. Still, I’ll share four of my strongest impressions.

— San Juan’s old town looks great, particularly considering that two monster hurricanes (Maria and Irma) rampaged through 7 years ago, leaving in their wake apocalyptic destruction. The hurricanes knocked out all the power and shut down nearly all the digital and physical highways. However, from our vantage in the old town (an Airbnb just down the street from the 500-plus-year-old cathedral), we saw no remnants of that disaster. The Puerto Ricans cleaned up and have rebuilt their lives, and today throngs of tourists are strolling among the brightly painted buildings, shopping, consuming prodigious amounts of rum, and gobbling down ice cream.

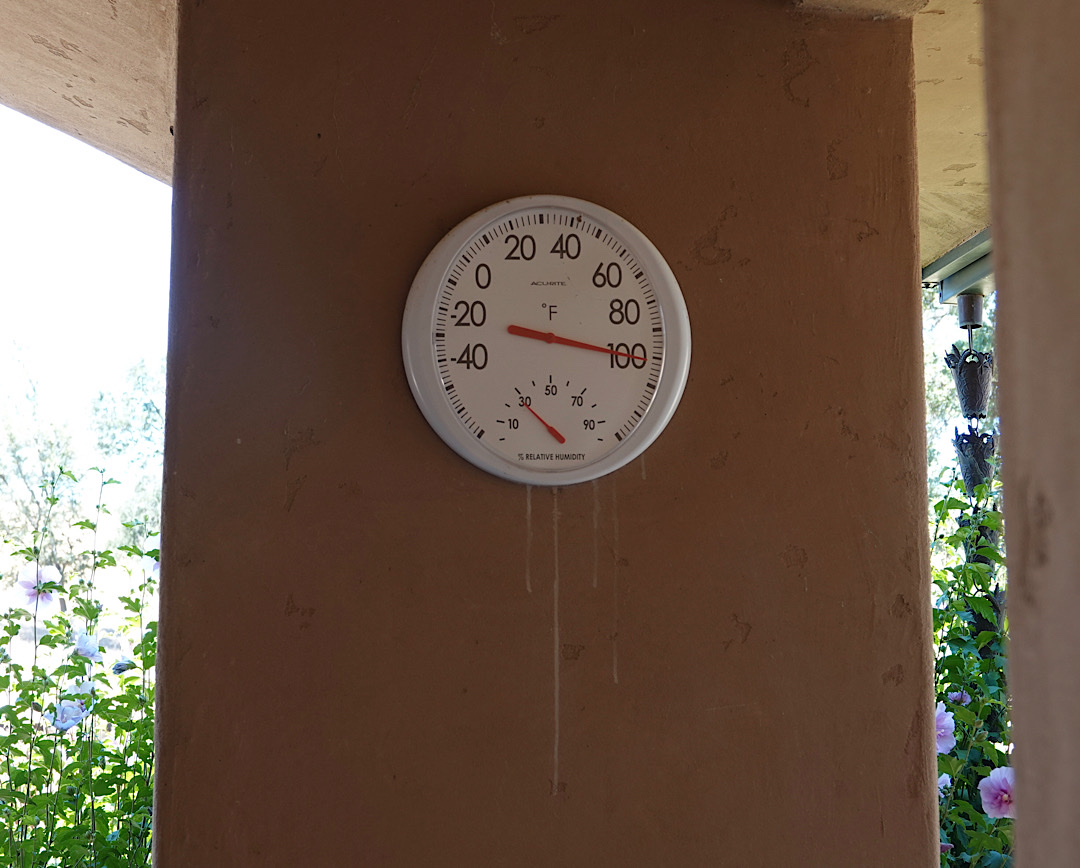

— The temperature hit 90 both weekend days, with so much humidity sweat dripped from us like drops of rain. This was a good thing. Old San Juan was so pretty and lively, had the weather been excellent, I might have felt tempted to move here. But not with weather like that.

— We ate four meals in restaurants (two lunches and two dinners), and all of them were better than anything we ate in the Lesser Antilles. There the food was solid but unexciting. Not so in San Juan.

— The town’s biggest attraction — El Morro — belongs on any list of the Most Impressive Forts in the World.

Sir Francis Drake tried (and failed) to overcome it. A second attempt by the British navy at the peak of its imperial power ended with the English slinking away in defeat. Today the United States park service shows a film there that nicely recounts the history of Puerto Rico and the role played in it by El Morro. The only bad thing about our visit was that Steve forgot to bring along his National Park Pass (which we would have allowed us to enter free).

Now, once again, we have no need for it. Yesterday afternoon we took the 40-minute flight on JetBlue from San Juan to the Dominican Republic, second largest island in the Greater Antilles.

The coastal vistas were as beautiful and empty as any I’ve seen anywhere.

The coastal vistas were as beautiful and empty as any I’ve seen anywhere.

Then there’s the weather — gray, sodden, and dreary for much of the year. In the height of summer, we enjoyed some sunny spells, but the daytime highs rarely surpassed 60. Nights, the temperatures dipped into the 40s.

Then there’s the weather — gray, sodden, and dreary for much of the year. In the height of summer, we enjoyed some sunny spells, but the daytime highs rarely surpassed 60. Nights, the temperatures dipped into the 40s.

The path ahead of us invariably looked shorter than the trees were tall. The scented air invigorated me, and the sculpted shapes surrounding us often stopped us in our tracks.

The path ahead of us invariably looked shorter than the trees were tall. The scented air invigorated me, and the sculpted shapes surrounding us often stopped us in our tracks.

It’s a landscape that competes with the most breathtaking anywhere, I think, and yet it rarely shows up on lists of the natural wonders of the world.

It’s a landscape that competes with the most breathtaking anywhere, I think, and yet it rarely shows up on lists of the natural wonders of the world.

We spent an afternoon exploring a canyon whose walls are coated with ferns.

We spent an afternoon exploring a canyon whose walls are coated with ferns.  We got close to wild elk.

We got close to wild elk.  Another morning we hiked up the mouth of the Big River.

Another morning we hiked up the mouth of the Big River. We resisted paying to drive through one of the touristic tree wonders.

We resisted paying to drive through one of the touristic tree wonders. But we drove the Avenue of the Giants, where the huge trees crowd so close to the road people put reflectors on them as a warning.

But we drove the Avenue of the Giants, where the huge trees crowd so close to the road people put reflectors on them as a warning.

…until we crossed the Golden Gate Bridge and were back in Civilization. We slept in Santa Cruz last night and will spend our final night on the road in Santa Barbara. All that will be anticlimactic. Those hikes through the otherworldly, timeless woods were the climax.

…until we crossed the Golden Gate Bridge and were back in Civilization. We slept in Santa Cruz last night and will spend our final night on the road in Santa Barbara. All that will be anticlimactic. Those hikes through the otherworldly, timeless woods were the climax. This summer marks my 30th anniversary as a home-exchanger. It was 30 years ago that Steve and I first traded our house in San Diego, that time for a spacious ground-floor apartment in a cool stone building in the most chic neighborhood in Paris. It had a private garden that opened onto a larger shared green space. After that we were hooked. Since then we’ve done almost 20 exchanges all over the planet.

This summer marks my 30th anniversary as a home-exchanger. It was 30 years ago that Steve and I first traded our house in San Diego, that time for a spacious ground-floor apartment in a cool stone building in the most chic neighborhood in Paris. It had a private garden that opened onto a larger shared green space. After that we were hooked. Since then we’ve done almost 20 exchanges all over the planet.

It’s a magical place filled with oak trees…

It’s a magical place filled with oak trees…

manzanita…

manzanita… …and other native flora. Near the house, we can there’s a pond ringed with emerald grass.

…and other native flora. Near the house, we can there’s a pond ringed with emerald grass.

On the afternoons when we decided not to venture out, we’ve hung out in the sprawling, baronial manor house. A swamp cooler protects the interior from the heat. (To my surprise, this system works as well as any air-conditioning unit and apparently costs a fraction of the price to run.)

On the afternoons when we decided not to venture out, we’ve hung out in the sprawling, baronial manor house. A swamp cooler protects the interior from the heat. (To my surprise, this system works as well as any air-conditioning unit and apparently costs a fraction of the price to run.)