Before we started this trip, I asked whether it would seem like we were visiting another country. In short order the question felt silly. For Alaska to feel foreign, it would have to be filled with something other than Americans. It is not. We met lots of folks who were either born in Alaska or had lived there for many years. To me they often seemed different, maybe even better, than residents of the other 49 states. But never did I feel like I was outside the US.

Steve commented that the locals made him think of the folks who would sign up to settle one of the exoplanets he invented in his science fictional Handbook for Space Pioneers, people happy to make a new life in a wild place filled with potential. To me it felt like time travel -– as if the locals (or I) had landed in another dimension, rather than just one hour off Pacific Standard Time.

I’ve been trying to untangle this impression because, to my surprise, what both Steve and I loved most about Alaska where the people we met.

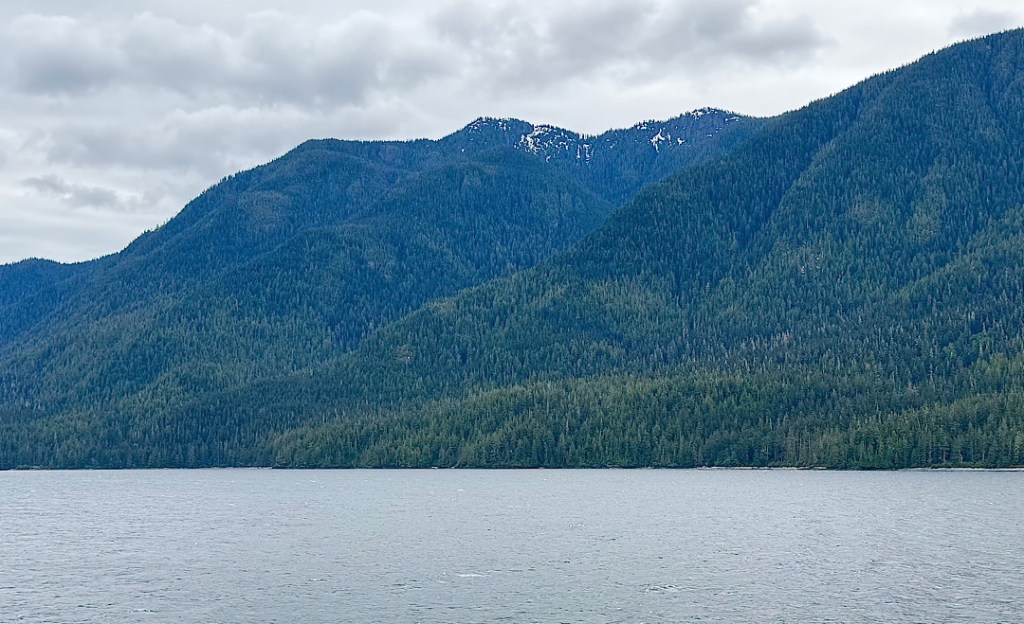

Not that other aspects of the state don’t live up to their billing. The landscapes are iconic.

But over and over, friendly encounters with local humans left us shaking our heads in amazement. One example: strolling around Sitka we ran into a woman I recognized from the previous night’s plane ride from Anchorage. She and I hadn’t spoken to one another on the plane, but she greeted me and told us all about the summer camp to which she was delivering her two youngsters. Somehow her little boy had forgotten to pack any extra pants for the week, so they were heading to the local white elephant store to do some shopping.

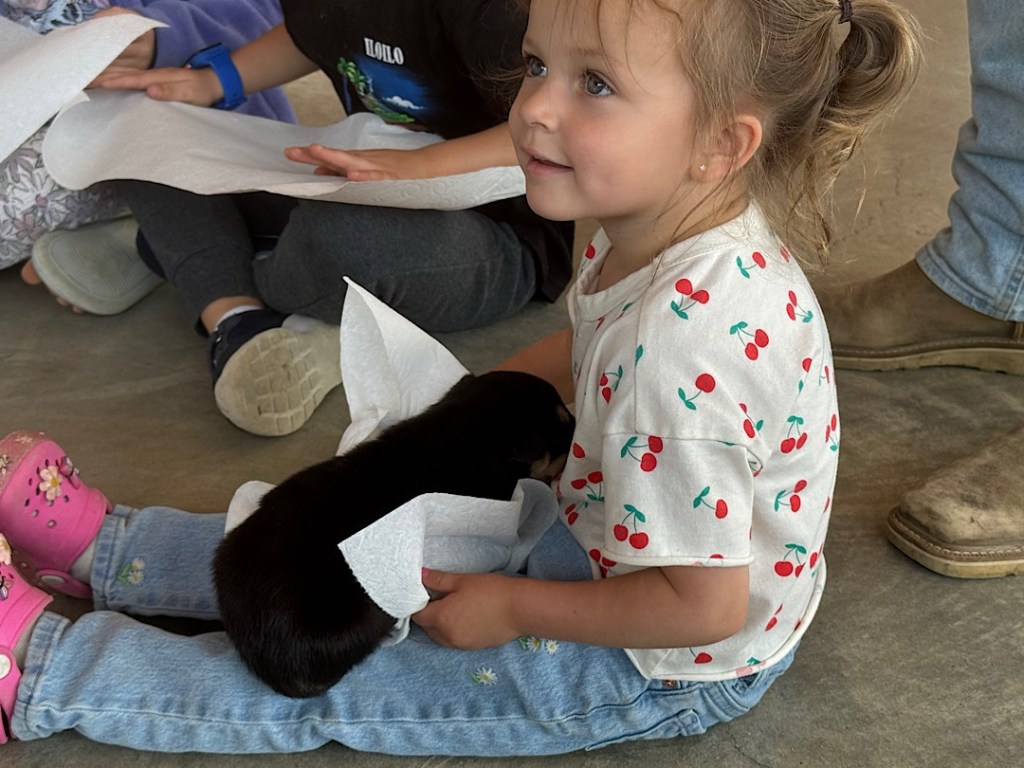

Of course Zack‘s not an Alaskan. He’s part of the legion of young people who flood in to work every summer, thrilled to be having such a big adventure. Some will return over and over. Some will wind up staying. Our home-exchange host in Juneau, Andy, did that. Now he and his wife have kids who grew up in Alaska and have already graduated from college. Andy’s had multiple careers over the years. The competition for jobs is low, he points out. If you want to find work and you can learn as you go, there are plenty of ways to make a living.

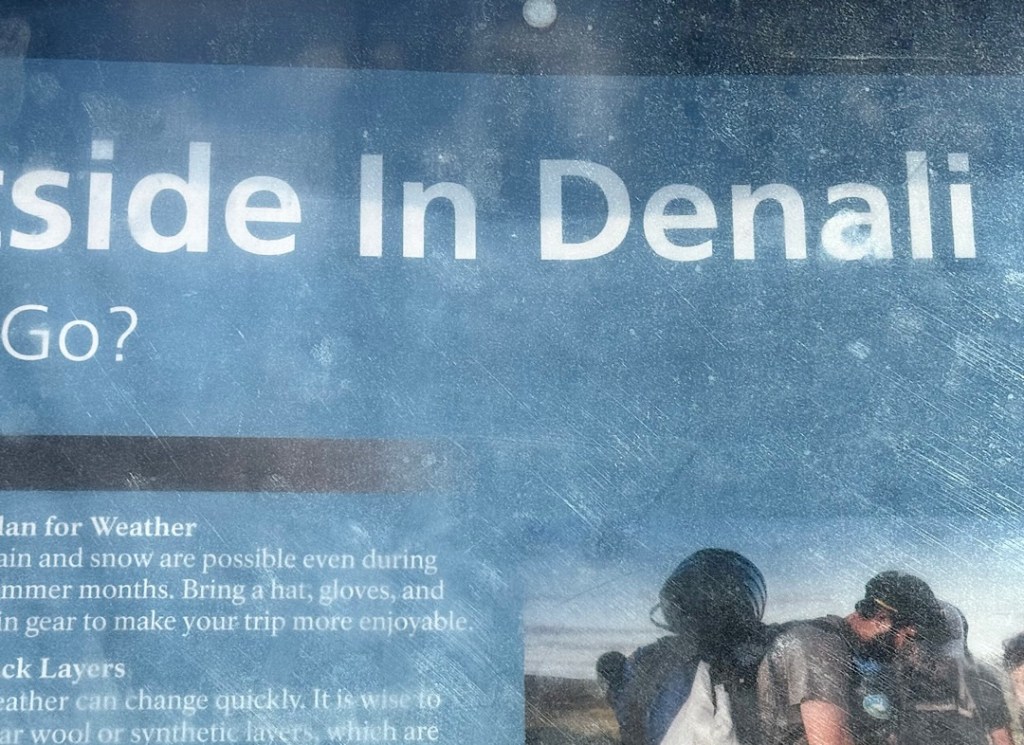

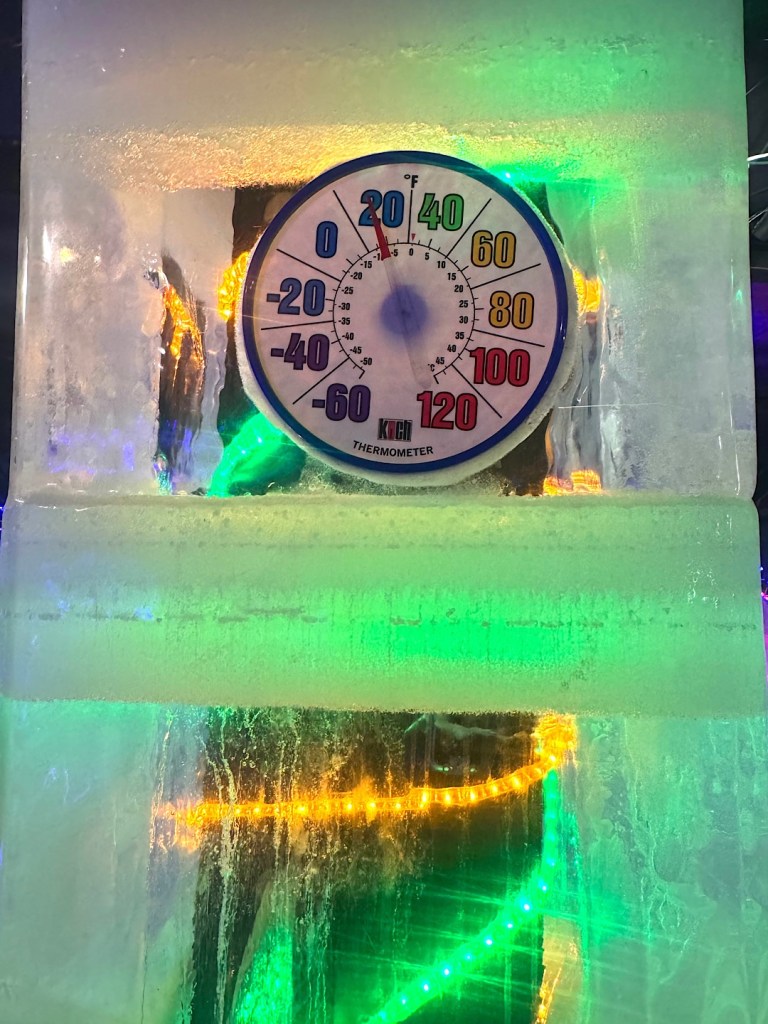

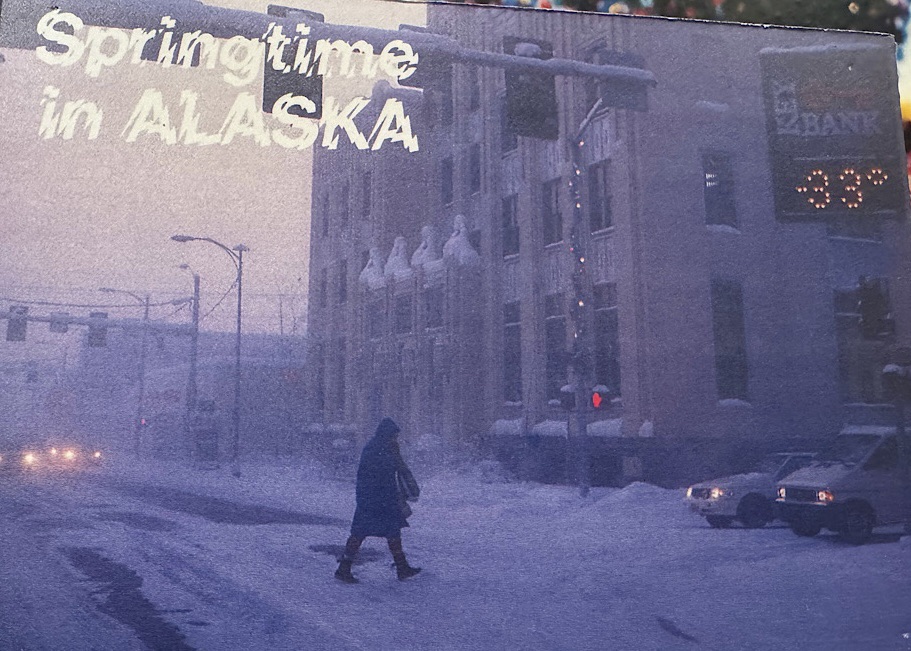

People seem to appreciate all that economic opportunity. Those who stay also have (or develop) a tolerance for a nasty weather and months of darkness.

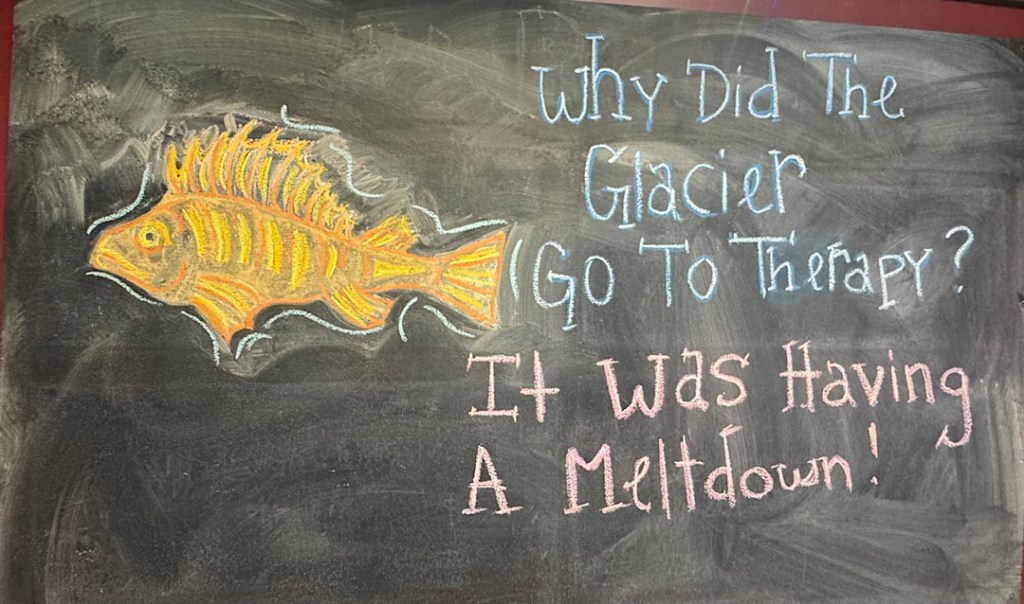

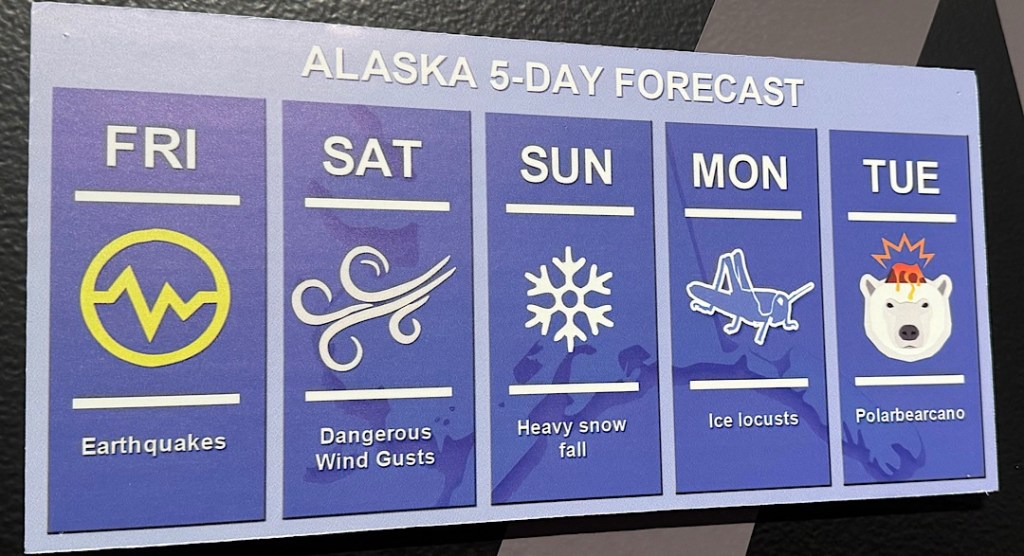

At any moment, an earthquake can wreck monstrous damage. Or it can trigger a dreadful tsunami. Volcanoes explode. Mountainsides or the snow piled up on them collapse and kill whatever’s in their paths. Go out for a run and you might meet up with an irritable mother bear. Because so much can go wrong, locals rely on helping out each other. They leaven that trust with humor.

It’s tempting to think about joining their ranks. If like Steve and me, you love growing baskets of fruits in your backyard year-round, that’s a bridge too far to cross. Still, it’s been fun to stand on the bridge for several happy weeks before returning to the sandals weather and sunny skies.