When Steve and I walked into the Fairbanks train depot (11 days ago) for the first leg of our Great Alaskan Railway adventure, we exclaimed almost in the same breath: this can’t be Amtrak. The depot was pretty and clean. The ticket sellers cheerful and efficient. To entertain waiting passengers, an elaborate model-train track had been set up in a side chamber. I wouldn’t say it all exceeded anything we saw in Japan last fall. But it wasn’t disgraceful.

We soon learned that Amtrak does NOT run it; the Alaska state government does. Built 100 years ago to serve early gold miners, it’s now popular with travelers. Planning this trip, I wanted to ride almost all of it, from Fairbanks to Denali, then continuing on to Anchorage, stopping there, then taking the line that runs down to Seward (on the southern coast of the main Alaskan peninsula) and back. Because the scenery promised to be so beautiful, I splurged and got us “Gold Star” seats in double-decker cars with wrap-around views through the glass dome and meals (included) in the dining room below.

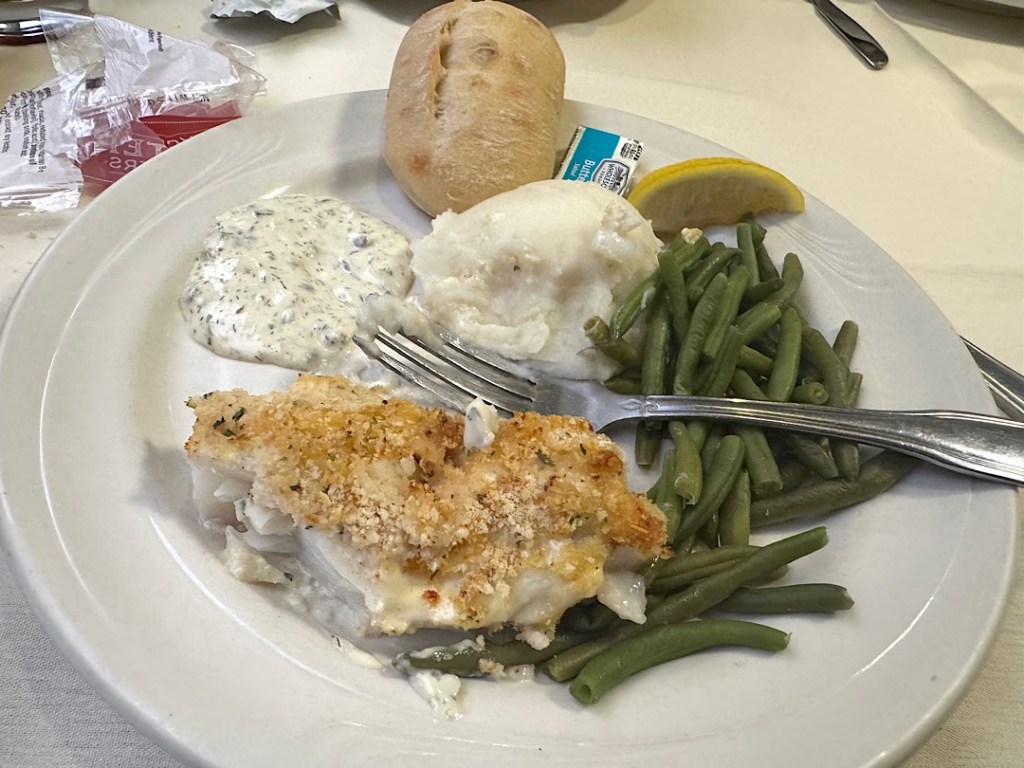

On the first two legs there was good news and bad. The good: our seats were not bad, and every time we were led down the winding brass-railed stairway…

… we ate well (breakfast on the four-hour Fairbanks to Denali run; lunch and dinner on the seven and a half hours from Denali to Anchorage.)

The scenery lived up to its billing.

We spotted some wildlife. Both those first two trains arrived on time. But how could this fill a blog post? Wallowing in middle-class comfort as you pass eye-catching wilderness is fun to experience but boring to read (or write). I wasn’t sure I was up to it.

Our third ride — from Anchorage to Seward — took a different turn, however. We boarded, went to the dining room, and shortly after Steve and I had ordered breakfast the train stopped. For a long while, nothing happened. Then very, very slowly, we began moving backward. Uh-oh.

An hour passed and we finished breakfast. Gossip about what had happened began percolating throughout the cars. We learned that 40 miles or so down the track, near Girdwood, a motorist had lost control of his car and flipped (four times, we later heard). In the course of this thrill ride he bounced off the track before smashing to a halt and dying.

Authorities were worried the disaster might have damaged the rails. It would take at least six hours for someone to inspect it, they finally announced.

Steve and I weighed our options. We could get off, return to our home-exchange house, and drive the Tundra to Seward and back (hoping to extract refunds from the train company.) Or we could get on a bus that we were told would arrive momentarily. We chose the bus.

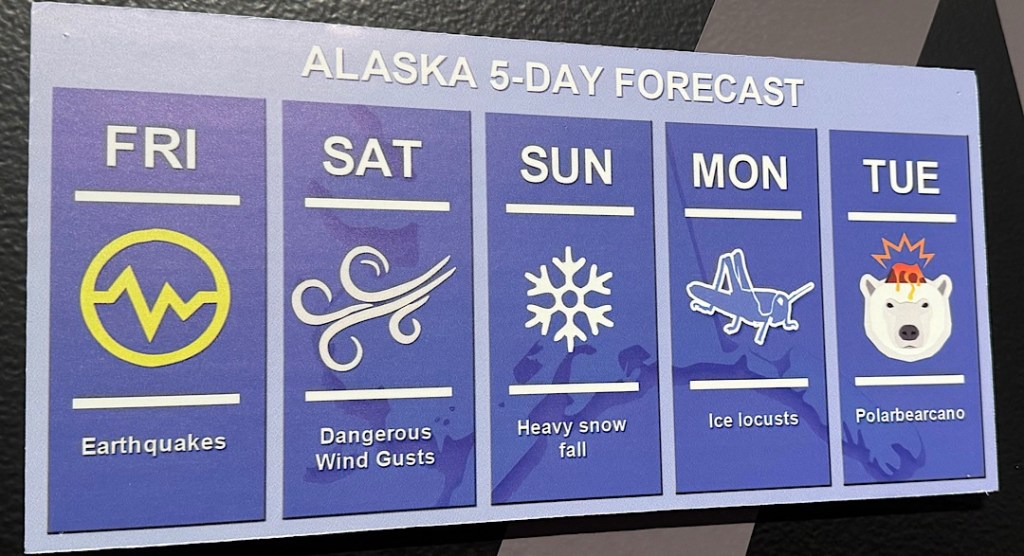

As we waited for it to show up, I chatted with our car’s bartender, a thin young blonde who had worked for the railroad for more than a half-dozen years. She said it was the first time she’d known a car crash to block or interrupt a section of the line. But other things had done so: wildfires and avalanches and rock slides among them.

She was perky and earnest. She said every time one of these bad things had happened, something wonderful had compensated for it. Once the train had been scheduled to arrive at 10:15 pm but didn’t get in until two in the morning. In the midst of the delays, a magnificent display of the aurora borealis began lighting up the sky, thrilling everyone on board. Or, on this run, the bartender pointed out, as we’d waited just outside the Anchorage depot, we’d been treated to the sight of a nearby foraging black bear. (I saw him but didn’t manage to capture the sighting with my phone.)

For me another unexpected compensation was the chance to ride to Seward on a bus driven by a guy named Steve who claimed to have logged three million miles on the road. His bus did arrive fairly promptly at the depot, and since the train goes so slowly (roughly 25 miles an hour), we arrived in Seward on the bus less than an hour after we would have via a punctual train.

The views were similar. But the commentary was much more eccentric than we would have gotten on the train.

Bus Driver Steve started talking just a minute after leaving the Anchorage depot and paused for breath only rarely the whole way to Seward. We learned he was born in Miami, studied for the ministry, and visited Alaska almost 40 years ago en route to work in Indonesia. But then he married a local Alaskan girl and lived what sounded like a happy life: raising kids, white-water tubing, fishing for monster trout. He’d been a world-class weight-lifting champion, the co-owner of multiple car dealerships, a masseuse. He’d worked as Sarah Palin’s personal driver. He explained how rescuers extract those foolish enough to get trapped by the quicksand in the Turnagain Sound mud flats at low tide. He shared with us the secret of his happy 38-year marriage. Also his father’s foolproof business philosophy. Also the name of the best Texas barbecue joint in Seward.

My Steve and I decided to try it. Bus Driver Steve showed up as we were mopping up the remains of our brisket. He ordered ribs and a pile of pulled pork and sat down on the picnic-table bench next to us.

We talked about the way Alaska could obliterate plans in the blink of an eye. At 8:30 that morning, he’d been sitting on his couch at home savoring the start of three days off work. The phone had rung and someone from the office had told him they needed him. There’d been an emergency. When that happens here, you don’t hesitate, he said. You do what you can to help out. “That’s just Alaska.”

I’m starting this post aboard the Eastern Express, the Turkish train that runs all the way from Turkey’s capital to Kars, near the Armenian border in the east. Travel constraints forced us to take the train westward. We flew from Ankara to Kars Friday morning (5/27) and had a couple of hours that afternoon to explore the town and its citadel on our own.

I’m starting this post aboard the Eastern Express, the Turkish train that runs all the way from Turkey’s capital to Kars, near the Armenian border in the east. Travel constraints forced us to take the train westward. We flew from Ankara to Kars Friday morning (5/27) and had a couple of hours that afternoon to explore the town and its citadel on our own.

We had brought our own bread and cheese, so this was lunch. And dinner.

We had brought our own bread and cheese, so this was lunch. And dinner.

Most of what we saw from our window seemed as devoid of people as the American West.

Most of what we saw from our window seemed as devoid of people as the American West.

The view from the bottom…

The view from the bottom…

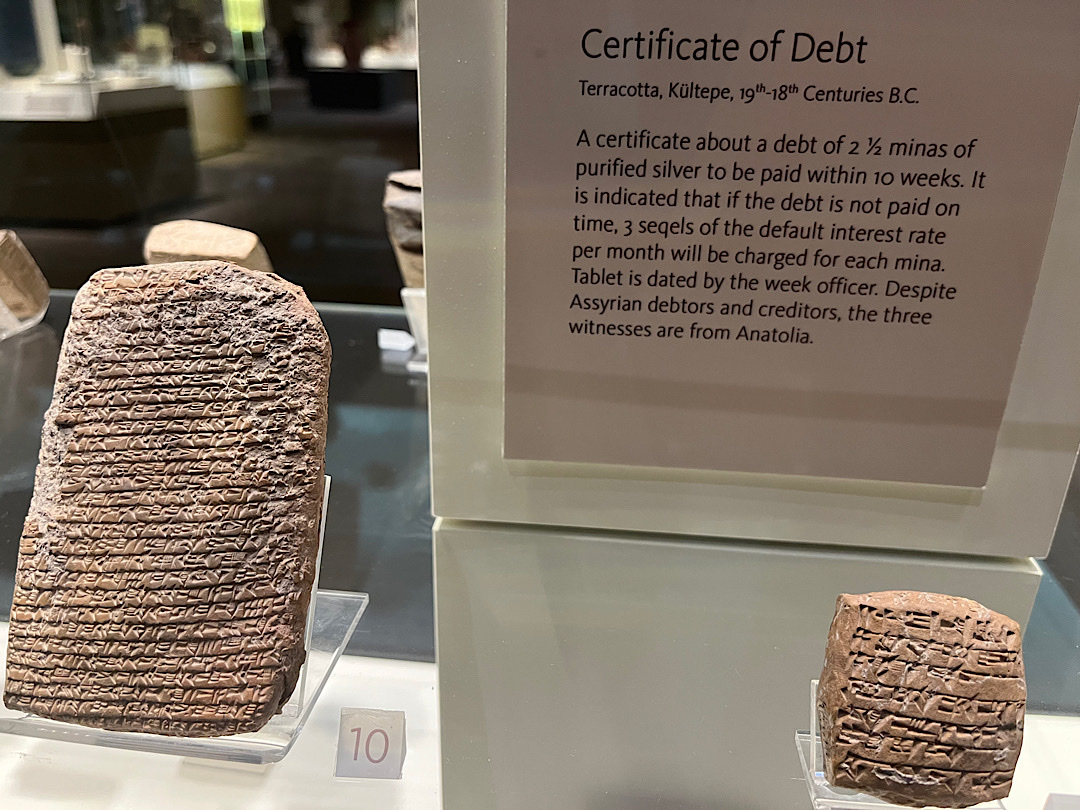

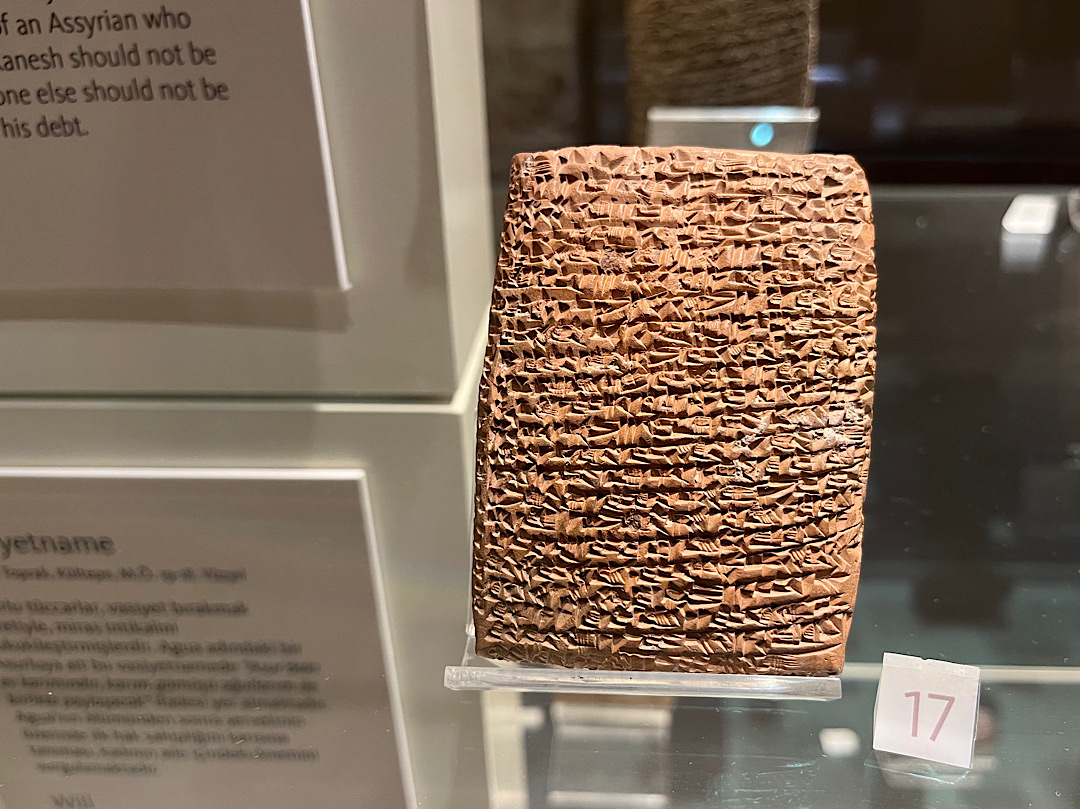

We took in the scene for about an hour, then caught another taxi to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations. (Taxis everywhere in Turkey have been easy to hail and are stunningly cheap. Many rides around town cost only a dollar or two.) I had read that this particular museum (another project of Ataturk’s) ranked among the best in the world for antiquities.

We took in the scene for about an hour, then caught another taxi to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations. (Taxis everywhere in Turkey have been easy to hail and are stunningly cheap. Many rides around town cost only a dollar or two.) I had read that this particular museum (another project of Ataturk’s) ranked among the best in the world for antiquities. …and there were any number of other charming goddesses…

…and there were any number of other charming goddesses…

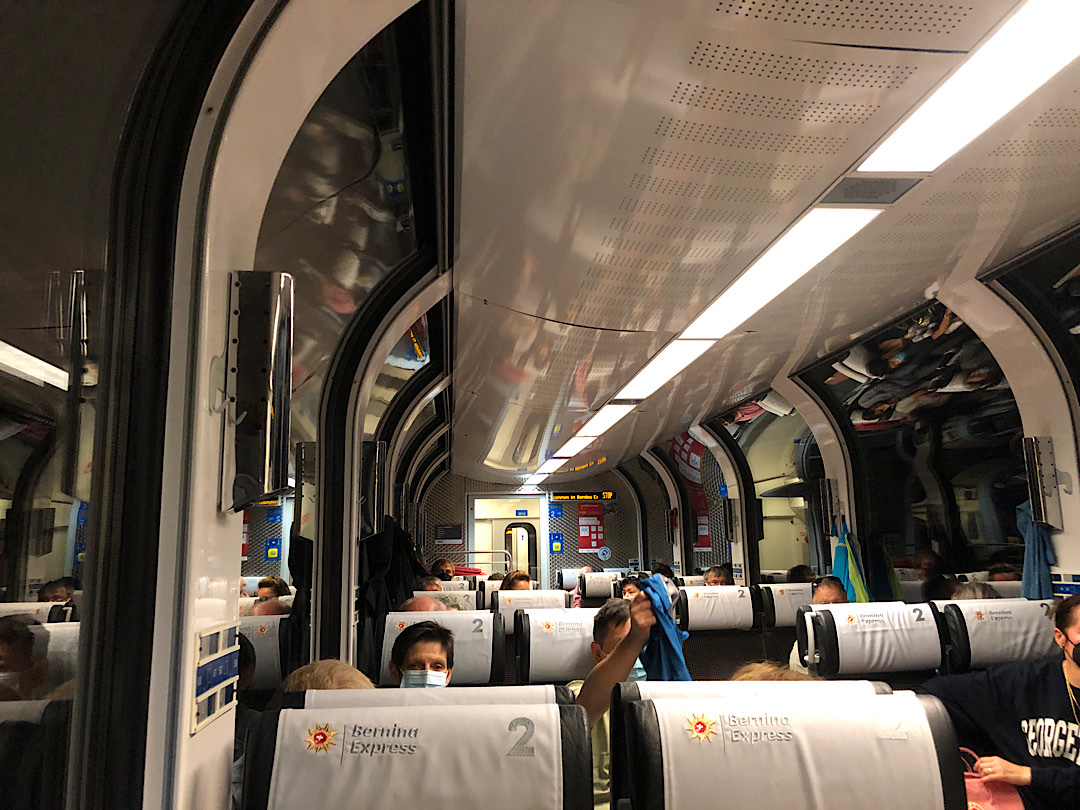

The other day when Steve glanced at our tickets for the Bernina Express, his jaw dropped. “Oh my God,” he breathed. “Am I really in seat #61?” “Yeah. You’re in 61 and I’m in 63. So what?”

The other day when Steve glanced at our tickets for the Bernina Express, his jaw dropped. “Oh my God,” he breathed. “Am I really in seat #61?” “Yeah. You’re in 61 and I’m in 63. So what?”

The Indian train arrived at its destination more than three hours late, after tortuous intervals of sitting and not moving. The Swiss one took off at 8:16 instead of 8:15 and arrived in the Italian town of Tirano at 12:51 instead of 12:49. Its roughly 4.5-hour-long route took us over one of the highest rail beds in the world, one constructed more than 100 years ago specifically for tourists. It posed devilish challenges to the Swiss engineers who designed it, but it helped make them into the pre-eminent experts on tunneling that they are today.

The Indian train arrived at its destination more than three hours late, after tortuous intervals of sitting and not moving. The Swiss one took off at 8:16 instead of 8:15 and arrived in the Italian town of Tirano at 12:51 instead of 12:49. Its roughly 4.5-hour-long route took us over one of the highest rail beds in the world, one constructed more than 100 years ago specifically for tourists. It posed devilish challenges to the Swiss engineers who designed it, but it helped make them into the pre-eminent experts on tunneling that they are today. Lots of tunnels on this run!

Lots of tunnels on this run! …but turned golden long before we crossed the Italian border. We had spiffy headphones that told us (in English) about the line’s history and highlights.

…but turned golden long before we crossed the Italian border. We had spiffy headphones that told us (in English) about the line’s history and highlights. The route literally winds through Heidi country — the part of the Alps where the book was set and movies were filmed.

The route literally winds through Heidi country — the part of the Alps where the book was set and movies were filmed. Bridges like this and sections of track that corkscrew through the mountains and meadows are among the attractions.

Bridges like this and sections of track that corkscrew through the mountains and meadows are among the attractions. In this view, the train is going under a circular bridge that it just traversed.

In this view, the train is going under a circular bridge that it just traversed. Views of glaciers and glacial lakes also triggered avalanches of camera clicks.

Views of glaciers and glacial lakes also triggered avalanches of camera clicks.

And there was a short rest stop that included traditional Alpine entertainment.

And there was a short rest stop that included traditional Alpine entertainment.