On Wednesday, Steve and I went to the fair. Technically, it’s called Expo 2025 Osaka, but it’s a world’s fair. Some 158 countries are participating, and more than 22 million people have attended since it opened April 13. The only reason I knew it was happening is because we visited Osaka last fall and saw posters promoting it. When it turned out we were going to be in Osaka again this October, the Expo called to me.

Throughout my life I’d read about the great early international expositions of the late 19th Century: Paris, London, Chicago. We have at least one friend who attended the 1964-65 New York City world’s fair and still recalls its wonders with awe. But neither Steve nor I ever had the chance to go to one. So in July, I bought tickets online.

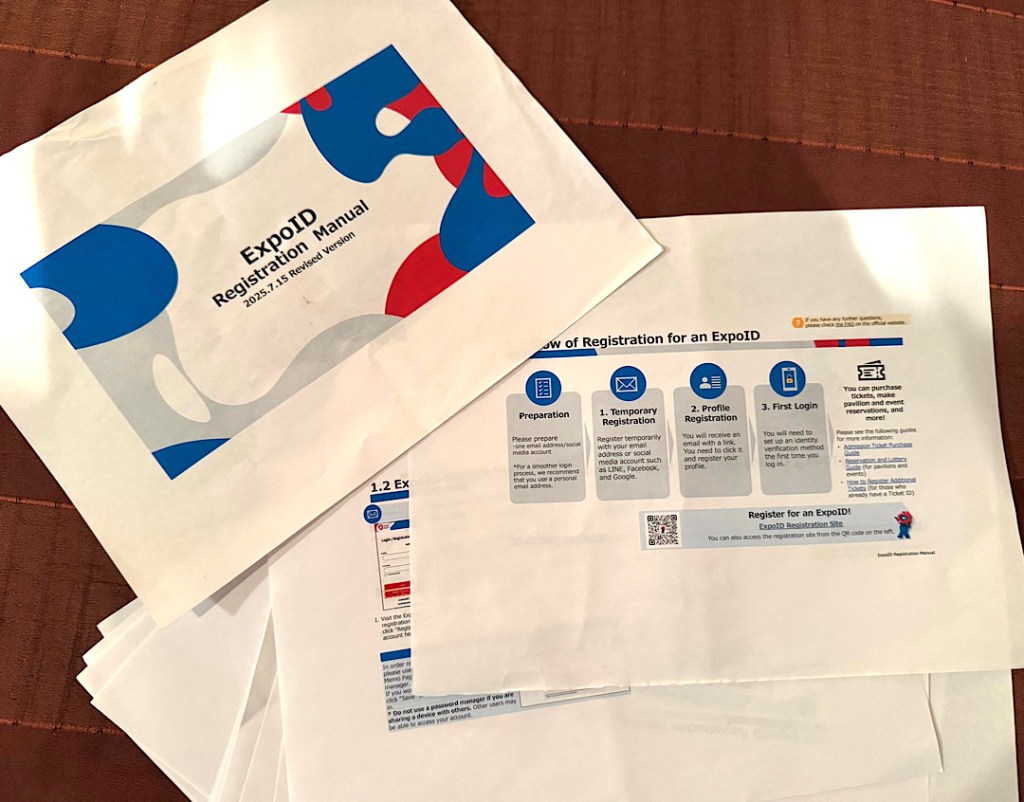

Now I know I should have done that months earlier. For one thing, the ticket-buying process was almost unimaginably complicated. The official Expo registration manual was more than 30 pages long.

After hours of study this past summer, I secured one-day admission for us. (This cost about $41 per person.) But I could only get tickets that let us enter the gates at 10 a.m.; the earlier slots were all gone. Worse: I had missed the deadline for making reservations to enter the pavilions at the heart of the fair-going experience.

There were one or two lotteries in which one might snag such reservations closer to the day we would be attending, but it was all so arcane and confusing (and we were traveling by then), I never succeeded. So we set off Wednesday morning with limited expectations:

- I wanted to walk the “Grand Ring.” To accommodate the expo, the Japanese built an artificial island in Osaka Bay. Then, encircling the heart of the fairgrounds, they built what’s being billed as the largest wooden structure in the world — a beautiful, elevated wooden walkway. No tickets were necessary to amble along it and take in the views of the bay, the city, and most importantly, the festival pavilions.

- Some pavilions didn’t require a reservation. I hoped to visit as many of those as possible until we ran out of energy.

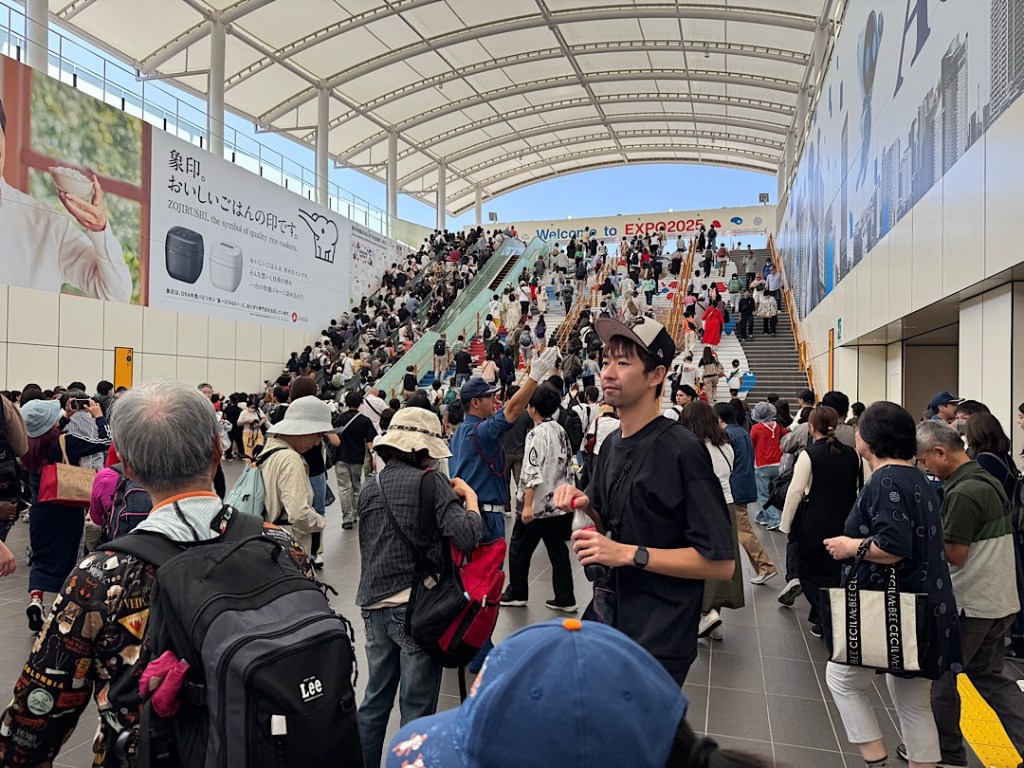

I also had been hoping the crowds that jammed the Expo in its initial months would diminish by the time we got there. What a laugh. My heart sank when we read in an English-language Osaka newspaper that this event had proven more popular than the Expo held in Aichi, Japan in 2005. Total visitors were expected to amount to around 25 million, with daily attendance building as the end of the event approached.

We took the metro from our hotel. As we neared the Yumeshima station just before 10 a.m., I began to believe it: more than 200,000 people DID share our plans for the day.

After about 40 minutes, we finally reached the security screeners, tapped our QR codes on a reader, and walked into the entry plaza. To orient ourselves we headed for the Grand Ring.

About halfway around, we were starting to feel hungry, so we descended to the fairgrounds to search for lunch. Long queues were already forming. We braced ourselves to join them when, miraculously, I spotted a second-story dining room that seemed overlooked by the mob. At the top of the stairs, a sign announced that it was fully booked. But to our relief and amazement, the hostesses said we could have a table if we promised to be out within an hour.

It was worth every one of the 8,400 yen it cost the two of us (about $57) to sit in the cool, serene room, listen to soft classical music, and eat artful, delicious food.

Those are the appetizers on the left. The main course on the right. We followed that with excellent coffee. I felt revived. That didn’t last for long.

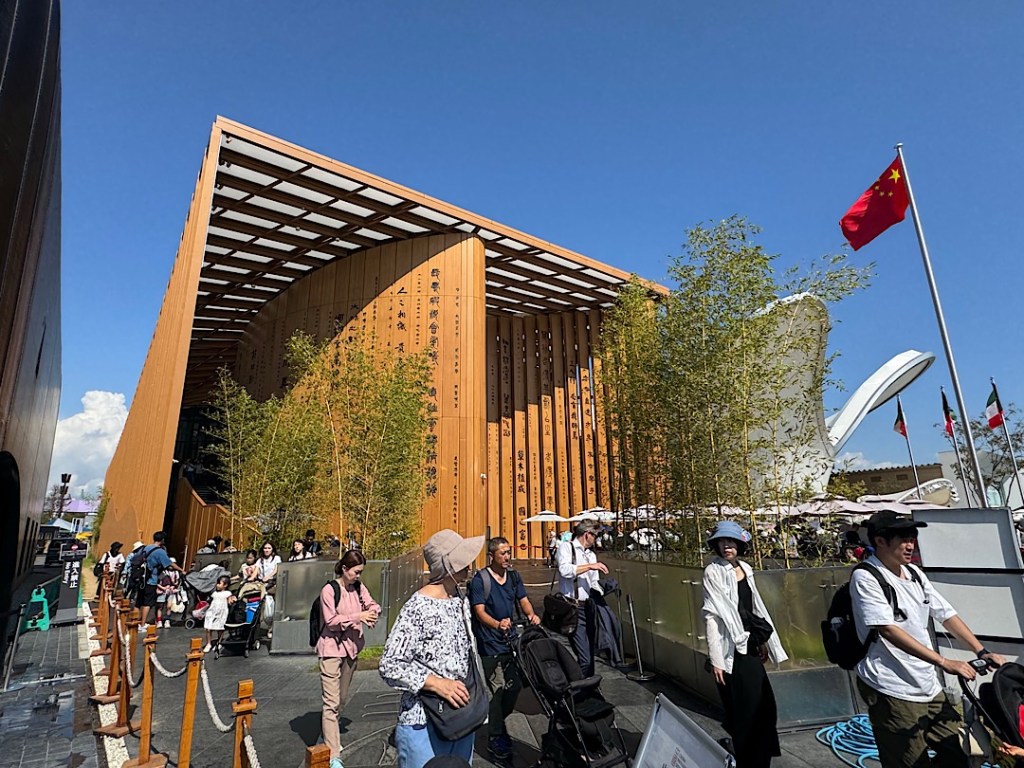

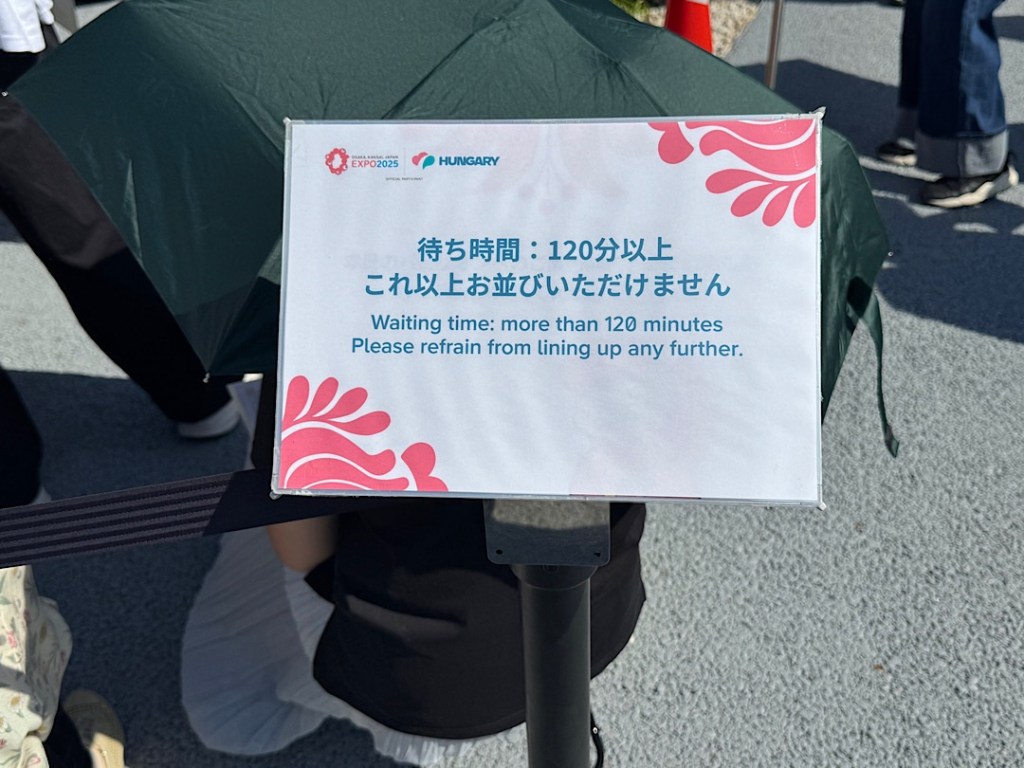

Outside again, the crowds had grown to mind-blogging proportions. Inching through the mob under a merciless sun, it became clear every major pavilion had an endless line encircling it.

As a last shot, we made our way to one of the large “commons” halls containing countries too little to have their own pavilions. You didn’t need a reservation to enter Commons A. It housed Barbados, Burundi, Bolivia, Comoros, Eswatini, Ghana, Grenada, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Kosovo, Krygystan, North Macedonia, Malawi, Mauritius, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Rwanda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Samoa, Seychelles, the Solomon Island, Suriname, Sri Lanka, Trinidad and Tobago, Tonga, Uganda, Yemen and Vanuatu. I had particularly wanted to visit this building because in Honiara we’d met an artist named Simon who’d told us he’d be there, representing the Solomon Islands. We’d promised to visit him. But a surly guard at the door held a sign announcing that admission was restricted. “Please come again later,” it read.

That was it. Sweaty and discouraged, we headed for the exit.

I’ll say this. If you have to be crammed into a relatively small space on a hot, sunny day with a couple of hundred thousand other humans, try to do it with Japanese. They never shove or shout with exasperation. Confronted with horrible lines, they seek out the end to join in, ever stolid. Their accomplishment at creating this event was as impressive as so many other things are in this country. Neither Steve nor I regretted going. It was worth just seeing the scene.

Still, giving the choice of attending another world’s fair or another Goroka festival, I’d take the naked, painted stone-age folk any day.