Our final stop on Shikoku was Matsuyama, the island’s biggest city. We only had a day and a half, but we made it to three of the city’s most highly praised sights:

One was Matsuyama Castle, one of the largest and best-preserved fortified dwellings in all Japan. We went on a rainy afternoon when it was easy to conjure up the samurai ghosts. (Good English translations of the displays helped.)

It was even more impressive than Kochi’s well-preserved castle, which we visited while there. The weather was better in Kochi, so when we climbed to the top-most level of the tower, we could better appreciate the great views.

The second major site we visited in Matsuyama was Ishite-Ji, one of Matsuyama’s many Buddhist temples. There I was disappointed to find the main building under renovation. But the grounds were wonderfully atmospheric…

We also crept into a a weird meditation tunnel chiseled into the rocky stone that abuts the temple complex.

Most exciting to me was catching sight of several arriving pilgrims. The Shikoku Pilgrimage is kind of a big deal on the island. Religious devotees try to follow a circuit that includes 88 temples; reportedly it takes 2-3 months to do it on foot. While achieving this would give one great bragging rights, it’s not on my bucket list. Still I was happy to glimpse some of those who were called by it.

The third Big Attraction in town is Dogo Onsen (onsen are hot springs and the bathing facilities around them). This one is said to be the oldest in Japan (3000 years old? So they say.) You have to pay an admission fee to enter the 130-year-old main resort building (Dogo Onsen Honkan). Because we had failed to bring towels and robes with us, we paid about $27 for the two of us to enter, bathe, and get not only towels and robes but also tea and cookies.

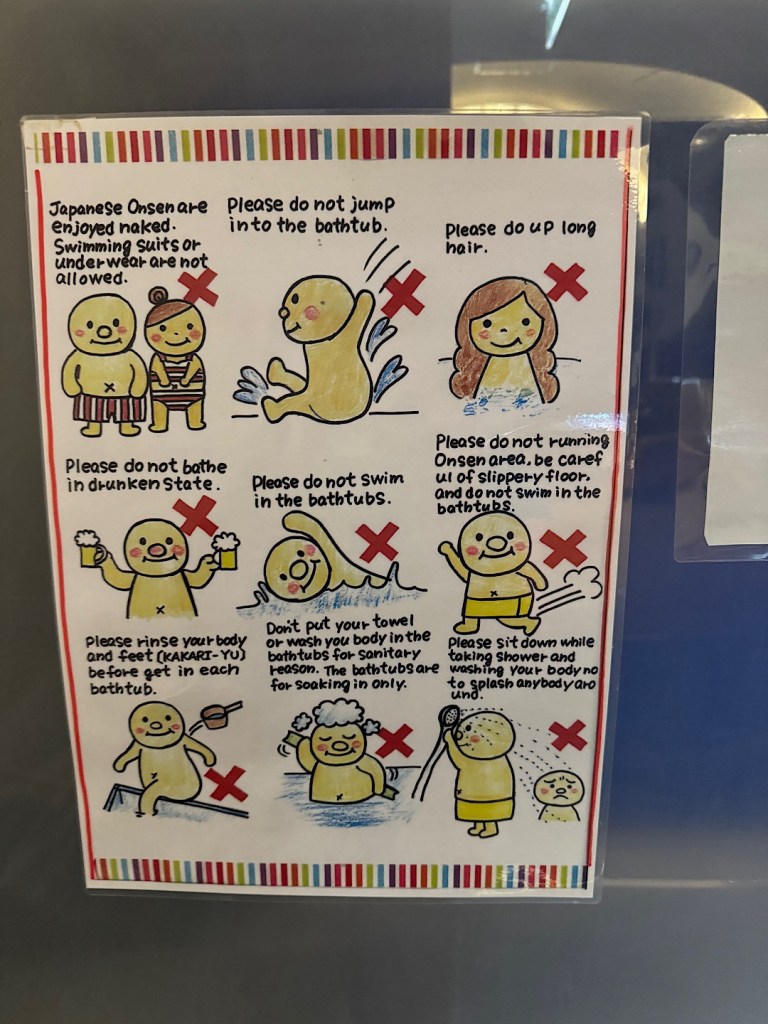

I should explain here that Steve’s not a huge fan of Japanese bathing, which we have done many times over the years. In 1979 we visited a town where the streets were filled with freshly scrubbed people strolling around in just robes and sandals. In 1982 we went to an onsen in the north where men and women soaked together, au natural, in lovely outdoor pools. On this trip, we used the communal baths at two places, both of which reminded Steve he finds nothing appealing about sitting in hot water with a bunch of other naked men. I’m more of a fan of the whole experience. I learned the rules of Japanese bathing way back on my first trip to Japan.

Steeping myself in very hot pools alongside other naked women is so wildly different from anything back home, I find the rituals interesting — and the hot-water dips relaxing.

At Dogo Onsen, Steve was a good sport and accompanied me into the spa (though we couldn’t soak together. In most places, it’s a sex-segregated activity.)

We enjoyed all three of these activities, but two other things happened that seemed more wonderfully, quintessentially Japanese. We stumbled on one while walking to the onsen through one of the town’s pleasant covered malls. An odd sight caught my eye:

It seemed the juice was squeezed from varieties of fruit hybridized and grown in Ehime Prefecture. We recognized a few like blood orange. But most were alien: Seminole juice? Buntan?

We picked out three to share; the total came to $5. None of them tasted exactly like the orange juice or tangerine juice or grapefruit juice we know from home.They weren’t blends of those, but squeezed from wholly different fruit, clearly related but different. As we walked in, customers of all ages were streaming in, happy to be trying something new, as people here tend to be.

Our other striking experience came on our final night on Shikoku. We’d wanted to eat somewhere good but close to our hotel; Google Maps showed us at least a dozen candidates within a 5-minute radius. We selected a highly rated one which looked to be just a half block down a little street almost directly across from where we were staying. We followed Google’s directions and were baffled to find a dark alley containing no sign of any commercial establishment (even though Google said it should be open.) We walked in various directions, increasingly frustrated. Steve was certain Google was simply wrong. But I pushed for one more careful walk through the alley before we caved and went to the nearest burger joint. And there it was!

We climbed an unpromising set of stairs…

…pushed open the door, and were greeted with a cry of welcome from the solitary figure working behind the counter. The room was lovely — sleekly elegant with lots of warm wood tones. Music played softly in the background. The only other person in the place was a single woman nursing a drink at the bar.

Steve and I wound up splurging on the Matsuyama Special. But what a fabulous range of deliciousness it included.

Then she presented us with a pretty paper bag containing Japanese snacks and some candy. Her gift to us for coming to dinner.

On December 20, five days after Steve and I returned from our nine-week Asian adventure, the New York Times published an article by its Frugal Traveler entitled “

On December 20, five days after Steve and I returned from our nine-week Asian adventure, the New York Times published an article by its Frugal Traveler entitled “ The Pollution — I knew the air in India might be bad, but I was unprepared for the depths of its wretchedness. In the course of our trip, I discovered that the weather app on my iPhone includes an “air quality index.” Since we’ve gotten back, I’ve been checking it and have learned that San Diego’s air typically falls in the 20-50 range (“Good”), occasionally dipping up to moderate pollution levels. When we arrived in Bengal, however, the index number was about 150 (“Unhealthy for sensitive groups”), and it got worse city by city after that, through “Unhealthy” then “Very Unhealthy” then “Hazardous” (in the 300-500 range). By the time we hit Jaipur in Rajasthan, it was over 500, literally off the chart. (“Don’t Even Think about What This is Doing to Your Lungs!!!”) I started coughing maybe a week after our arrival October 15 and still haven’t totally stopped (though I feel 99% better).

The Pollution — I knew the air in India might be bad, but I was unprepared for the depths of its wretchedness. In the course of our trip, I discovered that the weather app on my iPhone includes an “air quality index.” Since we’ve gotten back, I’ve been checking it and have learned that San Diego’s air typically falls in the 20-50 range (“Good”), occasionally dipping up to moderate pollution levels. When we arrived in Bengal, however, the index number was about 150 (“Unhealthy for sensitive groups”), and it got worse city by city after that, through “Unhealthy” then “Very Unhealthy” then “Hazardous” (in the 300-500 range). By the time we hit Jaipur in Rajasthan, it was over 500, literally off the chart. (“Don’t Even Think about What This is Doing to Your Lungs!!!”) I started coughing maybe a week after our arrival October 15 and still haven’t totally stopped (though I feel 99% better). Beyond the physical ill effects, the environmental despoliation was depressing. The air was foul not just here and there but every single place throughout the north and at least down to Mumbai (Bombay). Kerala in the far south was slightly better, though hardly pristine. Seen through clean air, much of the Indian landscape would be beautiful. Its absence is heartbreaking.

Beyond the physical ill effects, the environmental despoliation was depressing. The air was foul not just here and there but every single place throughout the north and at least down to Mumbai (Bombay). Kerala in the far south was slightly better, though hardly pristine. Seen through clean air, much of the Indian landscape would be beautiful. Its absence is heartbreaking.