I didn’t need to visit Hiroshima to understand that terrible things happen when you drop an atomic bomb on a city. I learned that lesson as a little girl, growing up during the Cold War; everyone knew about duck-and-cover drills and bomb shelters (the likes of which of course my family couldn’t afford). As a 7-year-old, I knew a single bomb could incinerate me and everyone I loved in an instant, and I thought poisons would linger in the air and ground for an unimaginable aftermath.

Visiting Hiroshima reminded me of all those things. Steve and I had three full days in the city, and the first thing we did on our first morning was walk to Peace Memorial Park, minutes from our hotel. We spent more than two hours in the Hiroshima Memorial Peace Museum.

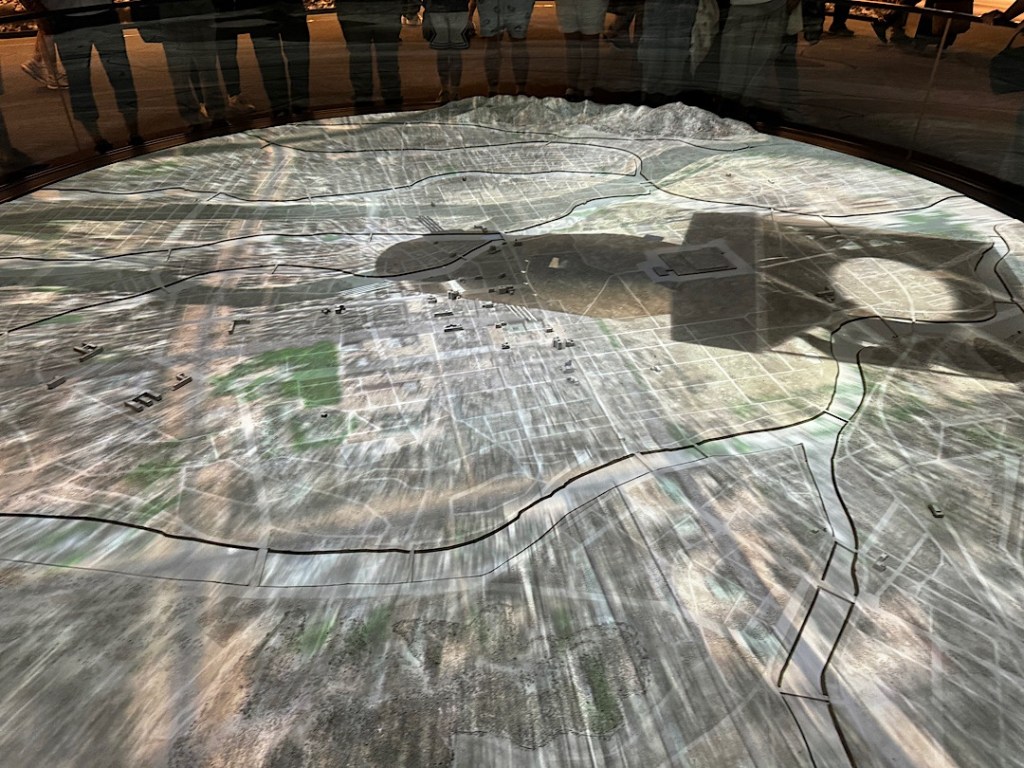

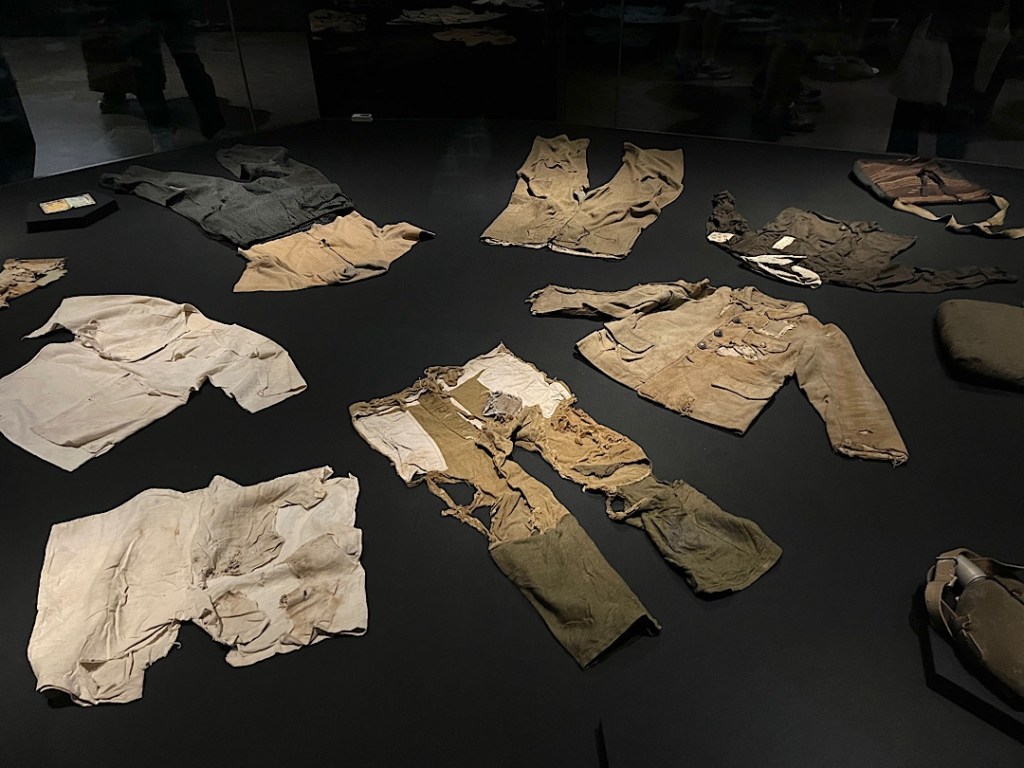

It contains displays that plead for peace and inveigh against future nuclear holocausts. But mostly, the museum is a literal chamber of horrors — evoking in shocking, gritty detail what a single bomb did to the city and the 350,000 men, women, and children who lived in it.

When we had absorbed as much as we could bear, Steve and I walked through the surrounding park in bright autumn sunshine.

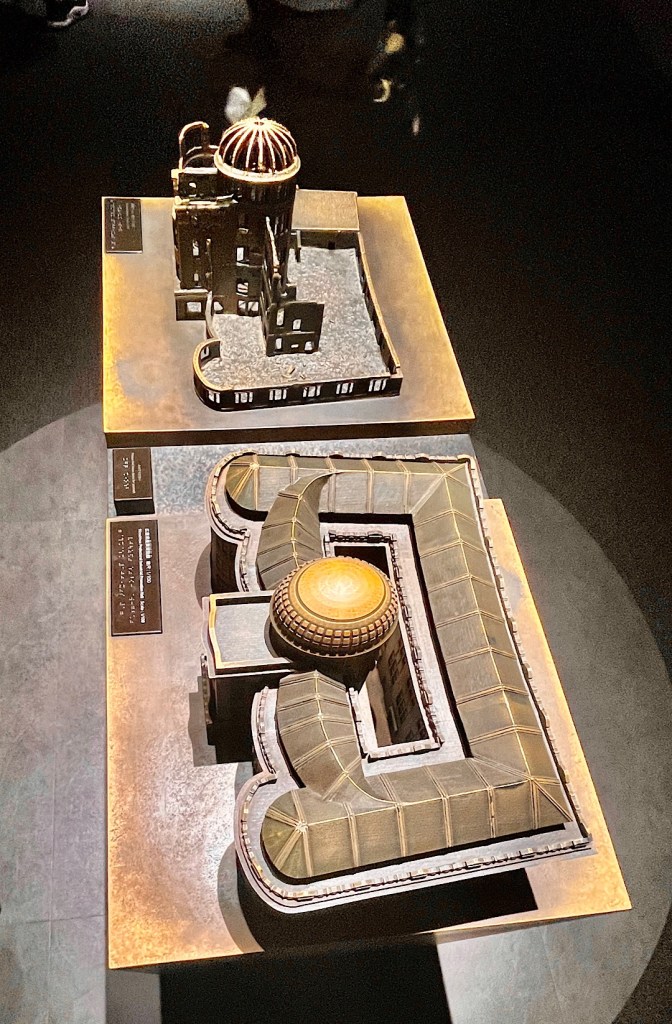

We appreciated several other striking monuments, including the Atomic Bomb Dome.

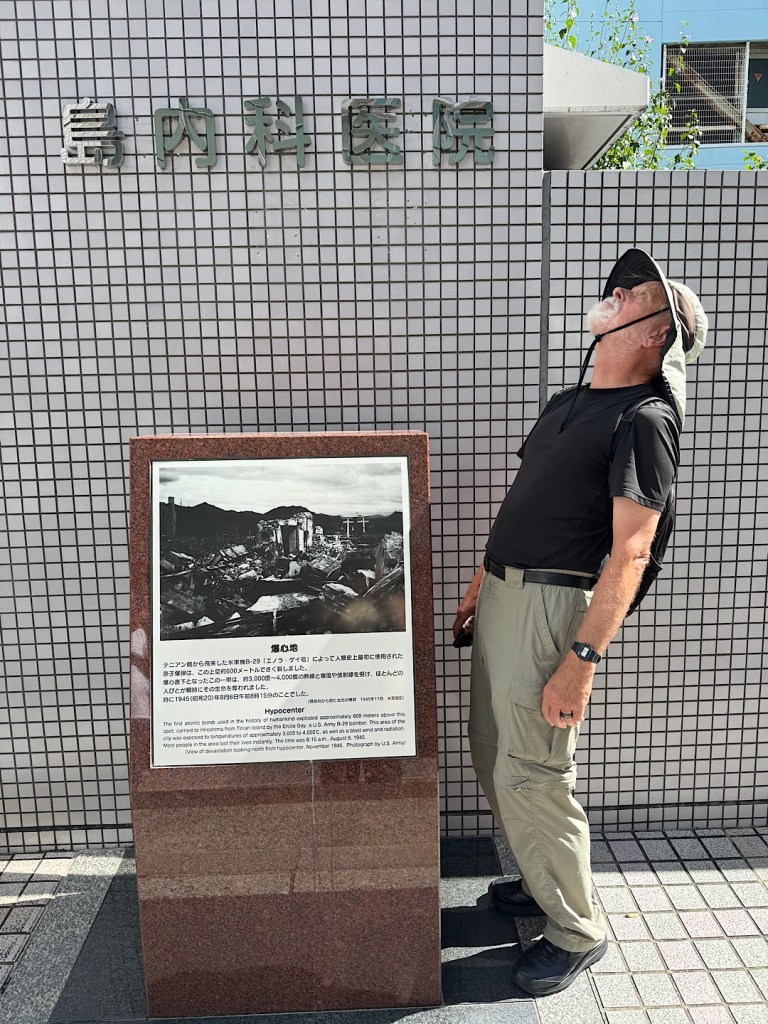

It’s a haunting landmark, but nearby Steve and I found something that fascinated us even more. We’d read about the bomb’s “hypocenter” — the spot directly below where it exploded. In the case of Little Boy that was about 2000 feet above the ground (roughly four blocks overhead.) We looked for the hypocenter in Peace Memorial Park, but it’s not there. Google Maps led us to it, a 3-minute walk from the Atomic Bomb Dome, outside the park and down a short block with a 7-Eleven on the corner. It’s so inconspicuous you could walk right by and miss it. But there is a little plaque, and looking up next to it gave me chills.

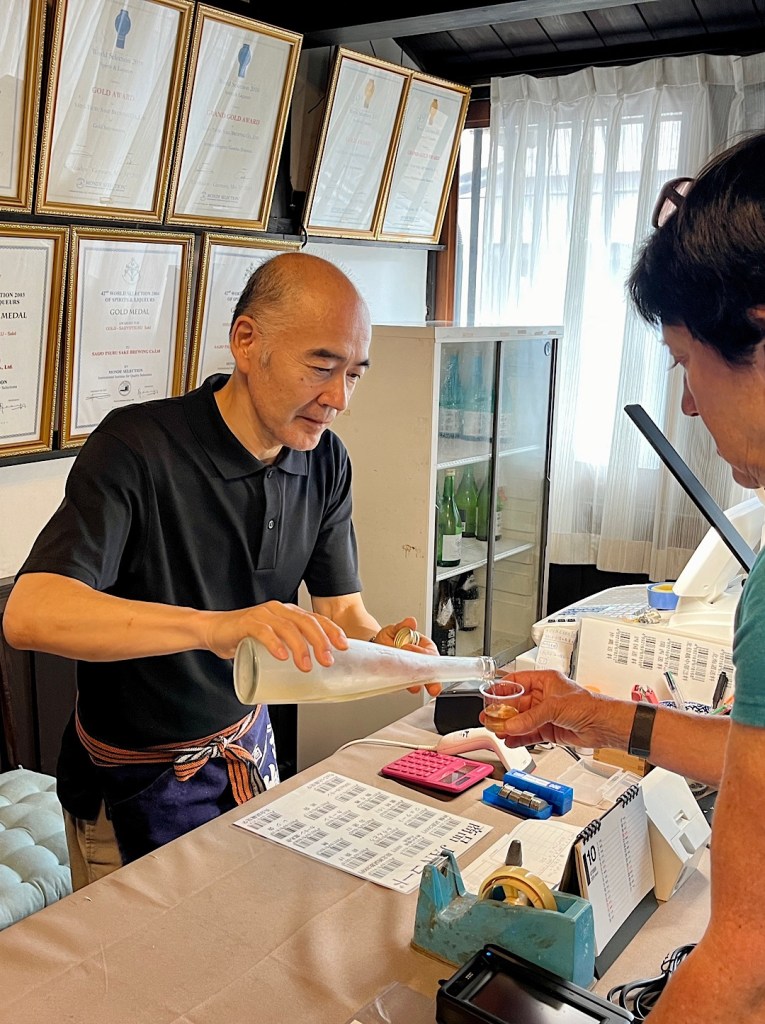

That was the sum of our A-bomb tourism. With the rest of our time, we did several fun things. On Sunday we rode a local train for about an hour to the town of Saijo, renowned for its concentration of craft sake breweries.

The town also boasts an archeological park containing a 1400-year-old kofun — one of the mysterious keyhole-shape burial mounds in which ancient Japanese rulers were interred.

The next day we took a river ferry from Peace Memorial Park out into the Inland Sea to reach Miyajima Island, famous for its striking Shinto shrine torii (ceremonial gate).

We ate more wonderful meals, strolled through gleaming commercial streets, and reeled at the thought that not in our lifetimes but close — so close! — everything everywhere here in all directions was smoking rubble. You’d never dream that was possible if you didn’t know better. Hiroshima today looks more prosperous and well-maintained than San Diego, and experts say radiation levels long ago dropped to no higher than they are anywhere else on earth.

I found that inspiring — evidence of how resilient people and their environments can be. Steve and I both were also struck by how many non-Japanese we encountered in Hiroshima —- more than anywhere else we’ve been on this trip. Large buses disgorge Germans and French and Americans and others. I heard people speaking Spanish and Hebrew and Russian and Korean and other languages I didn’t recognize. I wondered if maybe people all over the world feel Hiroshima belongs to all Earthlings — a warning.

Steve at one point expressed the wish that Putin and Biden and Bibi and Trump and Kamala would go to that museum and just look, long and hard, at those displays. Would it impact any of them? Maybe not.

So what’s a girl to do?

I’d say all three, only mine would be wine instead of saki.

Sobering, isn’t it? that we are the only ones who have dropped the bomb. It is definitely an anti-war memorial.

I’d say all three, only mine would be wine instead of saki.

Sobering, isn’t it? that we are the only ones who have dropped the bomb. It is definitely an anti-war memorial.