We didn’t go to Kodagu looking for elephants. We got interested in the area when a friend who has worked and traveled for pleasure in India told us Kodagu was a spice capital of south India, dense with gorgeous jungle. Then another friend put us in touch with an Indian friend who lives in Bangalore and owns two coffee plantations in Kodagu (also known as Coorg, the old British name). I emailed Sheila, asking if we might meet for a lunch, and in an amazing display of generosity, she invited us to stay in the guesthouse on one of her plantations. We made plans to spend three nights.

We didn’t go to Kodagu looking for elephants. We got interested in the area when a friend who has worked and traveled for pleasure in India told us Kodagu was a spice capital of south India, dense with gorgeous jungle. Then another friend put us in touch with an Indian friend who lives in Bangalore and owns two coffee plantations in Kodagu (also known as Coorg, the old British name). I emailed Sheila, asking if we might meet for a lunch, and in an amazing display of generosity, she invited us to stay in the guesthouse on one of her plantations. We made plans to spend three nights.

I haven’t written anything about our time in Bangalore and Mysore because we only had two nights in each. Both look more prosperous than any place we visited in the north, but sadly the air and traffic in Bangalore (“the Silicon Valley of India”) still wasn’t great. By far the highlight for us there was our rollicking three-plus-hour lunch with Sheila — a commanding, cosmopolitan lady with a surfeit of interesting opinions and insights and abundant good humor.

She had worried we might get bored with two and a half days in Kodagu, but this did not come to pass. I don’t know why the district isn’t on every Indian visitor’s list. For centuries (millennia?), Kodagu was an independent little state run by hundreds of clans. The clansmen were warriors but also farmers, growing rice along with spices and eventually coffee. Black pepper grows wild here. Trying to find a way to get to it is what led Christopher Columbus to stumble upon North America.

Kodagu didn’t become part of India until the 1950s, and it sounds like many folks today would like to go back to the independent old days. Living in their fertile valleys, shielded from the rest of the world by rugged mountain forests and the dangerous animals who inhabit them, blessed with clean air and a mild climate, Kodagu is a shangri-la — not just for people but for elephants.

We started our first day with elephants. Sheila’s farm manager, Arthur, found us a taxi ($43 for the whole day), and the driver headed northwest for an hour or so. Our destination was the Dubare Elephant Camp, an operation of the state (Karnataka) forest department. I sort of expected this to be a tourist attraction, and it was, but only in the loosest possible sense of that term.

We parked near a bank of the Cauvery River and joined a long queue of Indians waiting to board launches to ferry them to an opposing bank (43 cents per person for the boat ride; 29 cents for the camp admission). In about 15 minutes, Steve and I made it aboard a boat and quickly reached the camp. In the hour and a half we were there, no person, no signs, no brochures told us anything about what the camp is and how it functions. Maybe the Indians thought it was irrelevant. Most folks didn’t come here for helpings of wildlife education: the draw was watching the residents get their morning bath.

In about 15 minutes, Steve and I made it aboard a boat and quickly reached the camp. In the hour and a half we were there, no person, no signs, no brochures told us anything about what the camp is and how it functions. Maybe the Indians thought it was irrelevant. Most folks didn’t come here for helpings of wildlife education: the draw was watching the residents get their morning bath.

Young men were riding big old males and females and youngsters from an upper holding area down to the river… then using that ancient Asian-elephant-control tool, the hook, to make them lay down in the water…

then using that ancient Asian-elephant-control tool, the hook, to make them lay down in the water… or stand patiently while their tusks were cleaned with a sand-paste rub.

or stand patiently while their tusks were cleaned with a sand-paste rub.

Poke this baby into the tender spot behind one of those big ears, and you can get a 10,000-pound beast to do what you want!

Poke this baby into the tender spot behind one of those big ears, and you can get a 10,000-pound beast to do what you want!

For an additional 200 rupees ($2.87), one could go down onto the beach and join in the elephant-spa activity. I (naturally) could not resist, but Steve claimed he didn’t want to get wet and so opted to stay on the cliff top and take pictures.

Down on the beach, I edged up to the action, simply watching for a while. It was hard to tell what the elephants thought.

It was hard to tell what the elephants thought. It didn’t look like they hated it. But was it pleasurable?

It didn’t look like they hated it. But was it pleasurable?

Once or twice, one of the young mahouts interacted with a visitor… …as when one wrapped his charge’s trunk around this young lady’s neck, in response to a photo request. But most of the guys ignored the crowd gaping at them and concentrated instead on scrubbing the tough hides.

…as when one wrapped his charge’s trunk around this young lady’s neck, in response to a photo request. But most of the guys ignored the crowd gaping at them and concentrated instead on scrubbing the tough hides. They reminded me of car-wash attendants, irritable because of the long line of customers awaiting service.

They reminded me of car-wash attendants, irritable because of the long line of customers awaiting service.

I finally petted several animals… I tried to communicate good will with my touch. I ran my fingers over a few tusks, the source of so much elephant suffering and death. Then I rejoined Steve, and we walked to the high ground, where we found workers wrapping up brown rice within handfuls of hay.

I tried to communicate good will with my touch. I ran my fingers over a few tusks, the source of so much elephant suffering and death. Then I rejoined Steve, and we walked to the high ground, where we found workers wrapping up brown rice within handfuls of hay.

It did look to me like they enjoyed getting the tasty packages.

It did look to me like they enjoyed getting the tasty packages.

We made a couple of other touristic stops that day — toured a nature park; visited a large enclave of TIbetan Buddhist exiles. But our quirky, magical visit to the pachyderms overshadowed everything for me. That and the lunch we had with a friend of Sheila’s.

He met us near the nature park and took us to an exquisite riverside resort for lunch. Madhu is an amazing character: a coffee grower himself, but also a consultant to coffee growers all over the planet. His special (U.N.-recognized) expertise is in sustainable cultivation practices. We talked about coffee-growing and many other things; among them, the local elephants.

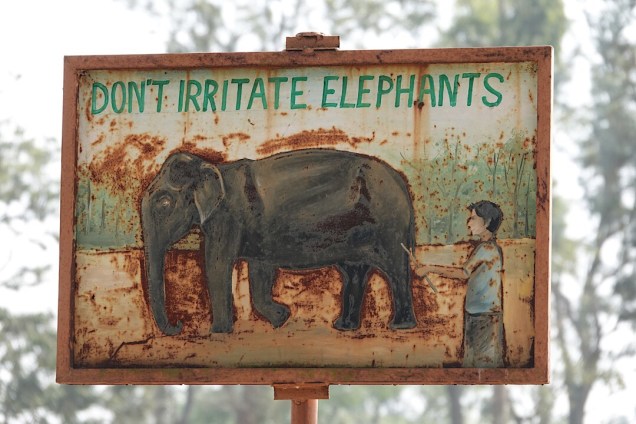

“You can kill a man and get away with it,” he declared. “But if you kill an animal here, you’re done for.” The Indian conservation and forestry officials were fierce and effective, he said, and in recent years, the local wild elephant population had grown well. We learned that elephants roam the roads and routinely barge onto fields in Coorg, mainly at night, when they’re foraging. When people harassed them or made them think their babies were threatened, encounters could get ugly. The elephants killed between 15 and 20 Kodagu residents annually, according to Madhu.

“But what does a grower do when a group of elephants comes onto his coffee plantation?” I asked.

The best course was to stay out of their way, Maddhu said. They would soon move on. Trying to chase them away was usually disastrous; frightened, stampeding elephants could do tremendous damage. Left alone, they rarely lingered. And in Kodagu district, an area about a third the size of San Diego County, elephants have lots of alternative eating grounds. Somewhere between a half and two-thirds of the district land is protected tropical rainforest. The only humans who can enter it are forest rangers and hikers with guides.

On our second full day in Coorg, Steve and I got one of those permits and two guides (the minimum acceptable number.) One carried a gun in his backpack, and the other, a 34-year-old guy named Chengappa, had a lot of experience and an okay grasp of English. He seemed to know a lot about the local elephants, so I pelted him with my questions. Elephants in India no longer can be taken from the wild and put to work (as they were for millennia), he told us. But the animals at the Dubare camp (all but the babies) were former “rogues,” individuals who had killed a human or otherwise caused great destruction. Such elephants were tranquillized and brought to a center, where they were (essentially) broken in spirit, re-educated, and used for a weird range of activities — everything from getting all gussied up to march in the biggest annual festival in Mysore, to helping with special logging problems, to being taken into the forest to participate in elephant funerals.

He seemed to know a lot about the local elephants, so I pelted him with my questions. Elephants in India no longer can be taken from the wild and put to work (as they were for millennia), he told us. But the animals at the Dubare camp (all but the babies) were former “rogues,” individuals who had killed a human or otherwise caused great destruction. Such elephants were tranquillized and brought to a center, where they were (essentially) broken in spirit, re-educated, and used for a weird range of activities — everything from getting all gussied up to march in the biggest annual festival in Mysore, to helping with special logging problems, to being taken into the forest to participate in elephant funerals.

Cheng said in his 8 years of working for the forestry department, he’d never heard of a guide or trekker being hurt by an elephant, but it wasn’t unimaginable, and the forest harbored other scary creatures — the Indian gaur (a buffalo-like animal similar in ferocity to the African Cape buffalo), pit vipers, tigers, leopards, jaguars. The only mammal I saw was a civet, swinging through a giant tree, but the ground was dense with spider webs, some of which built complex tube structures. This guy was about a half-inch tall. The forest also teemed with little leeches…

This guy was about a half-inch tall. The forest also teemed with little leeches… like this one, about an inch in length.

like this one, about an inch in length.

To protect ourselves from them, we all tucked our pants inside our socks, but several still fell from the trees and tried to attach themselves to my bare arms. Each time this happened I knocked them off with a yelp and a shudder.

We covered an eight and a half mile loop that included more tough climbs and descents than Steve and I have done in a while. The terrain we moved through was so dense and varied it felt Jurassic.

Sometimes we edged ourselves downward by stepping into little ledges created by the elephant’s footprints, dodging fresh elephant poop. Even though we saw no actual elephants, it warmed my heart to know they still claimed such a breathtaking sanctuary as their home.

Sometimes we edged ourselves downward by stepping into little ledges created by the elephant’s footprints, dodging fresh elephant poop. Even though we saw no actual elephants, it warmed my heart to know they still claimed such a breathtaking sanctuary as their home.

Besides sharing that space for a few hours, Steve acquired another souvenir from the hike. When he got back to Sheila’s and took off his shoes and socks, this is what he found:

All the leeches had fallen off, as Cheng said they would. We found them (fat and happy) inside Steve’s shoes, and we discarded them. Strangely enough, not one got to me. Another mystery of nature (or maybe sock mechanics).

“But there are plenty of middle-class people in India now, aren’t there?” I interjected.

“But there are plenty of middle-class people in India now, aren’t there?” I interjected. Just north of it begins a series of neighborhoods renowned for their maze-like bazaars. As it turned out, it was too early for many of the shops to be open, but we did pass guys carrying big tubs of fish on their heads

Just north of it begins a series of neighborhoods renowned for their maze-like bazaars. As it turned out, it was too early for many of the shops to be open, but we did pass guys carrying big tubs of fish on their heads and others selling them from tarps on the sidewalk.

and others selling them from tarps on the sidewalk. We passed trucks of suffering and doomed chickens that made me (briefly) consider never eating chicken again.

We passed trucks of suffering and doomed chickens that made me (briefly) consider never eating chicken again. The old Crawford food market (the exterior of which still bears beautiful sculpture work done by Rudyard Kipling’s father)

The old Crawford food market (the exterior of which still bears beautiful sculpture work done by Rudyard Kipling’s father) was just coming to life, and within it, I spotted a booth carrying all manner of canned drinks, including our beloved Schweppes (in both Indian and foreign sizes.) Steve was ecstatic. He bought six (Indian) cans from this guy.

was just coming to life, and within it, I spotted a booth carrying all manner of canned drinks, including our beloved Schweppes (in both Indian and foreign sizes.) Steve was ecstatic. He bought six (Indian) cans from this guy.

Had we gotten there too late? Were dabba-wallahs as endangered as those Rajasthani camels? I felt a wave of disappointment.

Had we gotten there too late? Were dabba-wallahs as endangered as those Rajasthani camels? I felt a wave of disappointment. It was indeed a thick congregation of dabbah-wallahs, loading up their conveyances. I hadn’t immediately recognized them because they were using so many insulated bags instead of the traditional tin canisters. Some had dozens of the lunch bags piled up on wooden hand carts…

It was indeed a thick congregation of dabbah-wallahs, loading up their conveyances. I hadn’t immediately recognized them because they were using so many insulated bags instead of the traditional tin canisters. Some had dozens of the lunch bags piled up on wooden hand carts… …while others stood by bicycles hung with motley receptacles.

…while others stood by bicycles hung with motley receptacles.

The face of the modern dabba-wallah.

The face of the modern dabba-wallah.

We wound up there because a listing in the “Activities” section of the Lonely Planet’s Udaipur chapter raved about Shashi’s cooking classes. I emailed to see if we could join one and got a response saying the 5:30 pm Saturday (11/17) class had two openings. This was a stretch; on Saturday we had to set the alarm in Jodhpur for 6 am to catch a train. After that five-hour journey, our taxi got stuck in a giant traffic jam. But we didn’t want to miss the opportunity, so precisely at 5:30 pm we walked into a trim little kitchen on the upper floor of a building down the street from our hotel.

We wound up there because a listing in the “Activities” section of the Lonely Planet’s Udaipur chapter raved about Shashi’s cooking classes. I emailed to see if we could join one and got a response saying the 5:30 pm Saturday (11/17) class had two openings. This was a stretch; on Saturday we had to set the alarm in Jodhpur for 6 am to catch a train. After that five-hour journey, our taxi got stuck in a giant traffic jam. But we didn’t want to miss the opportunity, so precisely at 5:30 pm we walked into a trim little kitchen on the upper floor of a building down the street from our hotel. We deep-fried them, then gobbled them down, dipped in two kinds of chutney (coriander and mango) both of which Shashi showed us how to make.

We deep-fried them, then gobbled them down, dipped in two kinds of chutney (coriander and mango) both of which Shashi showed us how to make.

We made the magic sauce, then we used it to makes several dishes, including curried chickpeas….

We made the magic sauce, then we used it to makes several dishes, including curried chickpeas…. deep-fried cheese in a tomato-butter sauce, and a vegetable pulao.

deep-fried cheese in a tomato-butter sauce, and a vegetable pulao. As each dish was completed, Shashi stacked it on its predecessors,

As each dish was completed, Shashi stacked it on its predecessors, a teasing metal tower that grew more maddeningly tempting as the hours went by, and we grew more and more tired and hungry. But there was more to learn, and lots of joking and laughter to distract us as we toiled. We made chapatti dough; learned out to knead it and cook it on a skillet.

a teasing metal tower that grew more maddeningly tempting as the hours went by, and we grew more and more tired and hungry. But there was more to learn, and lots of joking and laughter to distract us as we toiled. We made chapatti dough; learned out to knead it and cook it on a skillet. Many hands make good chapatti.

Many hands make good chapatti.

Somehow camels have become one of my favorite animals. I think this started in 2002 when I rode one in Luxor (Egypt), on the edge of the Sahara. It felt a bit like being on a gigantic rocking horse — fun and exhilarating and more comfortable than I expected.

Somehow camels have become one of my favorite animals. I think this started in 2002 when I rode one in Luxor (Egypt), on the edge of the Sahara. It felt a bit like being on a gigantic rocking horse — fun and exhilarating and more comfortable than I expected.

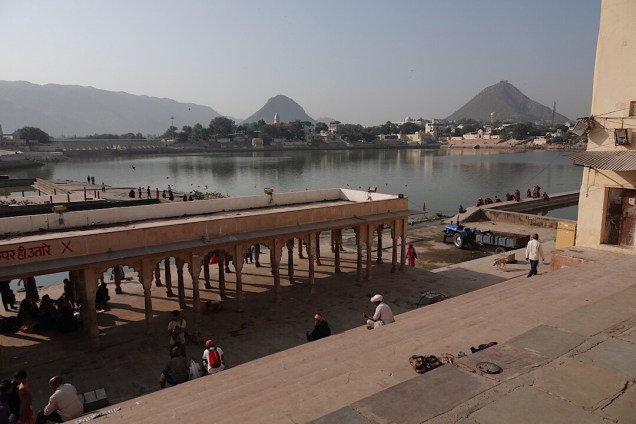

The devotees trickle in over a ten-day period, and they revel not only in the religious activities (praying, visiting various temples, smashing coconuts, launching lighted candles into the lake waters, etc.) but also shopping and enjoying Indian-style tourist attractions. They ride on camels or in carts pulled by them.

The devotees trickle in over a ten-day period, and they revel not only in the religious activities (praying, visiting various temples, smashing coconuts, launching lighted candles into the lake waters, etc.) but also shopping and enjoying Indian-style tourist attractions. They ride on camels or in carts pulled by them. They photograph snake charmers.

They photograph snake charmers. They ogle little girls walking on tightropes…

They ogle little girls walking on tightropes… or monkeys dressed up in little outfits.

or monkeys dressed up in little outfits. We spent hours wandering among the pilgrims. But I’d come for camels, not religious fanatics, so early on our first full day, we set out in the morning chill to find the hump-backed giants. (By noon, temperatures in Pushkar always climbed to the mid- to high-80s, but they plunged every night.) In the open grounds beyond the Brahma Temple, we found more camels assembled than I’ll ever see again in my life:

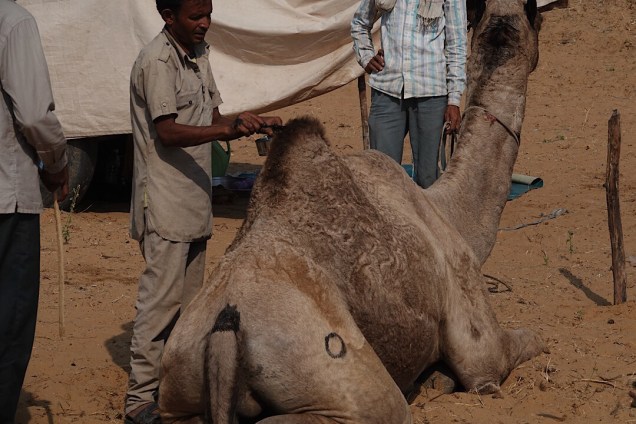

We spent hours wandering among the pilgrims. But I’d come for camels, not religious fanatics, so early on our first full day, we set out in the morning chill to find the hump-backed giants. (By noon, temperatures in Pushkar always climbed to the mid- to high-80s, but they plunged every night.) In the open grounds beyond the Brahma Temple, we found more camels assembled than I’ll ever see again in my life: thousands of them, most staked together in small groups or being groomed by their owners.

thousands of them, most staked together in small groups or being groomed by their owners.

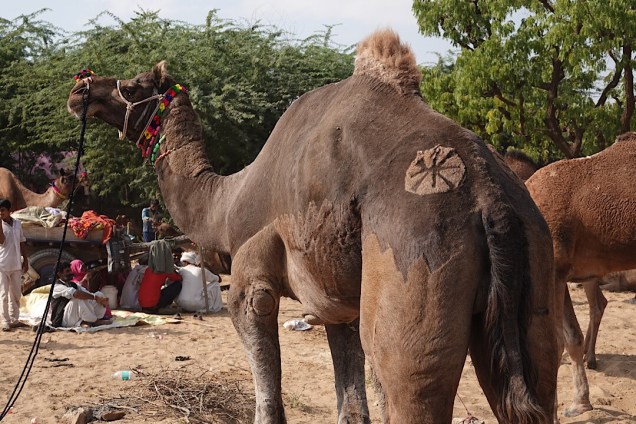

The backward swastika has nothing to do with Nazis. It’s an ancient Hindu symbol. Herders paint their animals in various ways to jazz them up.

The backward swastika has nothing to do with Nazis. It’s an ancient Hindu symbol. Herders paint their animals in various ways to jazz them up.

From the humans’ body language, we sometimes identified negotiations in progress. From the camels’, it appeared that some were bored…

From the humans’ body language, we sometimes identified negotiations in progress. From the camels’, it appeared that some were bored… But some were curious.

But some were curious. Overwall the scene felt surprisingly low-key, and we returned on our final day to see if the pace had accelerated.

Overwall the scene felt surprisingly low-key, and we returned on our final day to see if the pace had accelerated.

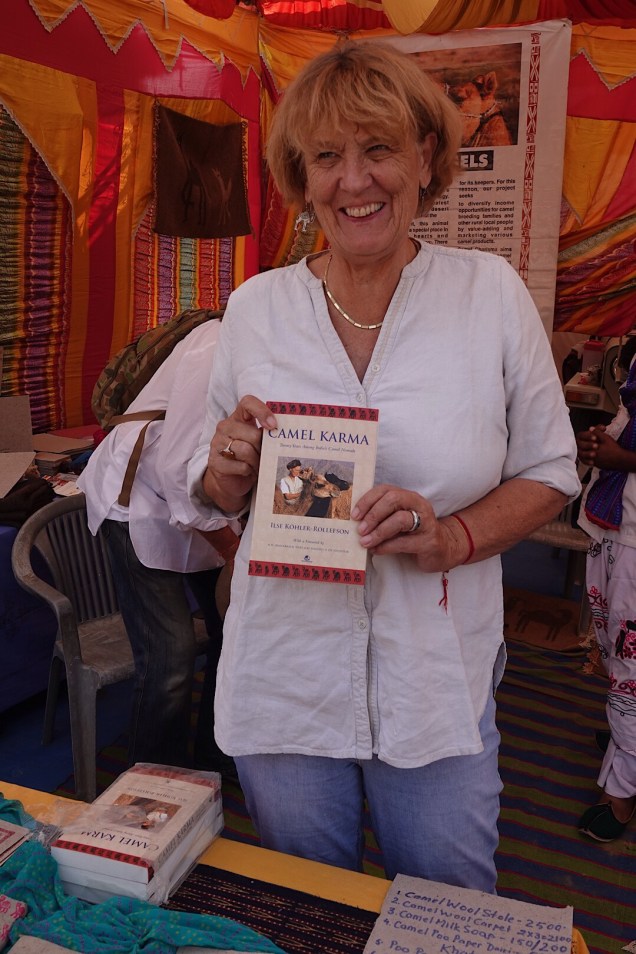

A talk blonde older woman in the back of the booth joined our conversation. She was a German anthropologist named Ilse Kohler-Rollefson who’d spent 20 years living among the camel nomads (and almost as amazingly, had lived for several years in San Diego and taught at San Diego State). She and her colleague explained that the NGO had helped start the first camel dairy in India. They were also lobbying for protection of traditional grazing grounds. The aim was to find ways for the herders to continue earning enough to survive.

A talk blonde older woman in the back of the booth joined our conversation. She was a German anthropologist named Ilse Kohler-Rollefson who’d spent 20 years living among the camel nomads (and almost as amazingly, had lived for several years in San Diego and taught at San Diego State). She and her colleague explained that the NGO had helped start the first camel dairy in India. They were also lobbying for protection of traditional grazing grounds. The aim was to find ways for the herders to continue earning enough to survive. We ran into Ilse too as she was buying an ice cream bar, and she told us that someone had delivered a rousing speech at the municipal center.

We ran into Ilse too as she was buying an ice cream bar, and she told us that someone had delivered a rousing speech at the municipal center. Among middle-aged Indians, the full-figured look is a common one. Now we better understand why.

Among middle-aged Indians, the full-figured look is a common one. Now we better understand why. A typical lunch: cashews in a cream sauce, peas and cheese in a mild spicy red sauce and yummy garlic/butter naan.

A typical lunch: cashews in a cream sauce, peas and cheese in a mild spicy red sauce and yummy garlic/butter naan. On the breakfast buffet this morning: deep-fried herb-flavored rice patties. We both thought they were yummy.

On the breakfast buffet this morning: deep-fried herb-flavored rice patties. We both thought they were yummy. Note that the cook is squirting the batter into the boiling oil. Then you dip the results into sugar syrup and get what’s known as jalebis.

Note that the cook is squirting the batter into the boiling oil. Then you dip the results into sugar syrup and get what’s known as jalebis. Although we didn’t eat them from the street vendor, the ones we sampled in our hotel were surprisingly likable.

Although we didn’t eat them from the street vendor, the ones we sampled in our hotel were surprisingly likable. like these…

like these… and these.

and these. We entered through this gate and saw ladies in their new finery making offerings to various gods.

We entered through this gate and saw ladies in their new finery making offerings to various gods. So many men and women and children were out to view the decorations and buy desserts, the honking of taxis and tuk-tuks made it hard to hear the Diwali music blaring over loudspeakers.

So many men and women and children were out to view the decorations and buy desserts, the honking of taxis and tuk-tuks made it hard to hear the Diwali music blaring over loudspeakers. like this street.

like this street. This was more the norm, though.

This was more the norm, though. Not smoky enough for you? Burn some garbage!

Not smoky enough for you? Burn some garbage! The current maharajah, just 20, still lives in the palace at the heart of the city.

The current maharajah, just 20, still lives in the palace at the heart of the city.

That’s him, with the sword, surrounded by his grandmother, mom, and siblings.

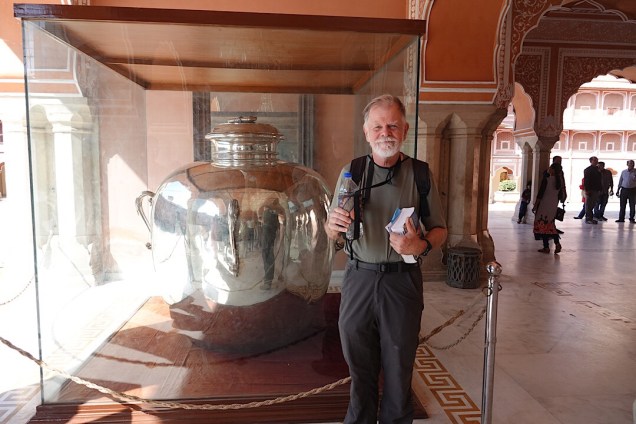

That’s him, with the sword, surrounded by his grandmother, mom, and siblings. The palace is filled with interesting objects, such as this giant silver vessel. One of the maharajahs had it filled with water from the Ganges, for him to drink on a trip to London. (Note that Steve prefers to travel lighter.)

The palace is filled with interesting objects, such as this giant silver vessel. One of the maharajahs had it filled with water from the Ganges, for him to drink on a trip to London. (Note that Steve prefers to travel lighter.)

You can ride up the hill to it on an elephant.

You can ride up the hill to it on an elephant.

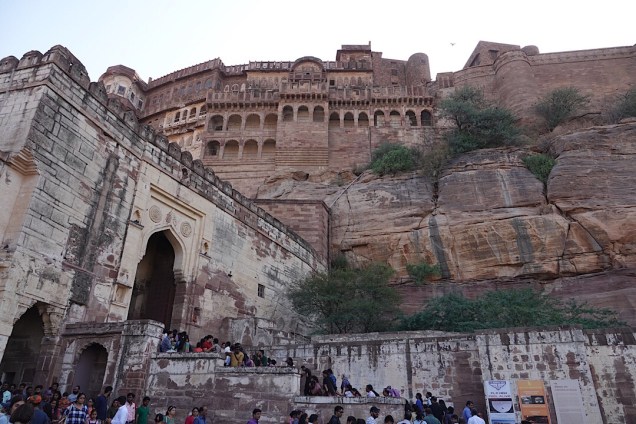

The spikes in the door were supposed to deter war elephants from battering in the gate.

The spikes in the door were supposed to deter war elephants from battering in the gate. One view of the so-called Pleasure Room in the palace within the fort.

One view of the so-called Pleasure Room in the palace within the fort. The ceiling in one of the maharajah’s bedrooms.

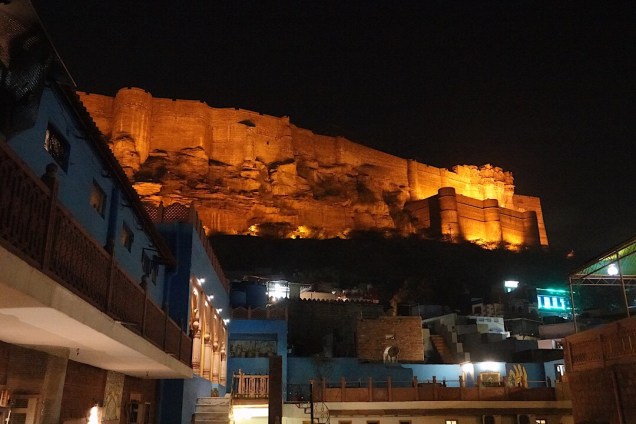

The ceiling in one of the maharajah’s bedrooms. The view of Jodhpur’s Mehrangarh Fort at night, from the little haveli where we stayed.

The view of Jodhpur’s Mehrangarh Fort at night, from the little haveli where we stayed. Now I know the secret to seeing a tiger in Ranthambore National Park. Go in May or June, the peak of the dry season. Many of the trees in the park lose their leaves; streams dry up; waterholes shrink. With the undergrowth reduced and the tigers’ drinking sources limited, 90% of safari-goers encounter the animal superstars. The only problem: temperatures at this time of year typically are 110 to 120 degrees.

Now I know the secret to seeing a tiger in Ranthambore National Park. Go in May or June, the peak of the dry season. Many of the trees in the park lose their leaves; streams dry up; waterholes shrink. With the undergrowth reduced and the tigers’ drinking sources limited, 90% of safari-goers encounter the animal superstars. The only problem: temperatures at this time of year typically are 110 to 120 degrees. Our crew that morning, minus the guide, who took this photo.

Our crew that morning, minus the guide, who took this photo. This was India, home to 1.2 billion humans, yet it felt like a less crowded place, say, a (smoggy) forest in Idaho after heavy rains that had made everything lush and green. At times the vegetation pressed in so close we had to duck to avoid being scratched in the face by branches. We passed marshland…

This was India, home to 1.2 billion humans, yet it felt like a less crowded place, say, a (smoggy) forest in Idaho after heavy rains that had made everything lush and green. At times the vegetation pressed in so close we had to duck to avoid being scratched in the face by branches. We passed marshland… …and stands of banyan trees that took our breath away.

…and stands of banyan trees that took our breath away. Here and there, we glimpsed the 1000-year-old fort that topped a distant cliff top. (Later we read that the wall surrounding it is almost 5 miles long.)

Here and there, we glimpsed the 1000-year-old fort that topped a distant cliff top. (Later we read that the wall surrounding it is almost 5 miles long.)

Spotted deer…

Spotted deer… Sambar deer…

Sambar deer… Nilgai (a type of Indian antelope).

Nilgai (a type of Indian antelope). Wild boar…

Wild boar… Crocodile.

Crocodile. A cormorant drying his wings in the sun.

A cormorant drying his wings in the sun. Owls snoozing in a tree hole.

Owls snoozing in a tree hole. So many peacock they reminded us of seagulls in San Diego.

So many peacock they reminded us of seagulls in San Diego. This guy is known as the dentist of the jungle. Guides told us that they all but climb into the tigers’ mouths, cleaning their teeth, a mutually beneficial service that the tigers tolerate.

This guy is known as the dentist of the jungle. Guides told us that they all but climb into the tigers’ mouths, cleaning their teeth, a mutually beneficial service that the tigers tolerate. We all but ignored all the other animals we passed. We searched one area after another. With the sun getting closer to the horizon, we waited on a high ridge overlooking a canyon; listened to the birds. Saw no tigers.

We all but ignored all the other animals we passed. We searched one area after another. With the sun getting closer to the horizon, we waited on a high ridge overlooking a canyon; listened to the birds. Saw no tigers.

So now I know a second way to see a tiger in India: get lucky.

So now I know a second way to see a tiger in India: get lucky.

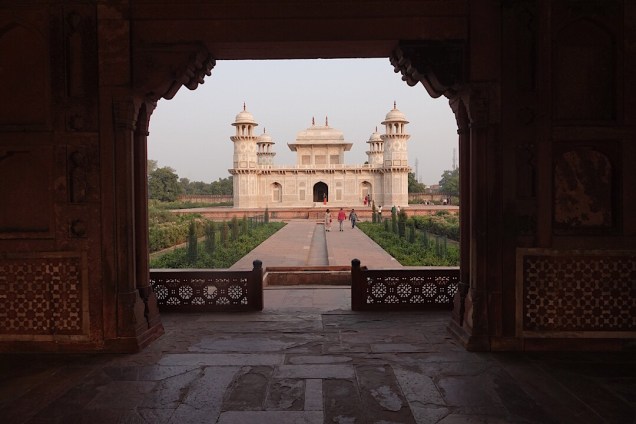

It’s pretty from every angle…

It’s pretty from every angle… And pretty up close.

And pretty up close. I’d had to guess how many selfies are taken there. Weird posing is also super popular.

I’d had to guess how many selfies are taken there. Weird posing is also super popular. This shows less than half the interior space.

This shows less than half the interior space. Nice, but nothing like Big Mama.

Nice, but nothing like Big Mama. This was as good as it got.

This was as good as it got. Here’s the street in front of Faiz’s home. The road leading to the Oberoi looks quite different.

Here’s the street in front of Faiz’s home. The road leading to the Oberoi looks quite different. We rode in a beautiful new taxi to the train station, walked in, and learned that our train this morning had been delayed. It probably would arrive at least eight hours late. We called Faiz, who hopped in his own car, drove it to the station, collected us, and helped us arrange a private car and driver.

We rode in a beautiful new taxi to the train station, walked in, and learned that our train this morning had been delayed. It probably would arrive at least eight hours late. We called Faiz, who hopped in his own car, drove it to the station, collected us, and helped us arrange a private car and driver. A nice one!

A nice one! But I got a message saying there’s no refund “if train is running more than 3 hours late or train is canceled.”

But I got a message saying there’s no refund “if train is running more than 3 hours late or train is canceled.” unlike this poor truck that we passed.

unlike this poor truck that we passed. Set among them are about a dozen structures. The area is breathtaking; even at a distance, it ranks among the greatest ceremonial sites Steve and I have visited: Angkor Wat, Machu Picchu, Teotihuacan.

Set among them are about a dozen structures. The area is breathtaking; even at a distance, it ranks among the greatest ceremonial sites Steve and I have visited: Angkor Wat, Machu Picchu, Teotihuacan.

These ladies were replanting the lawn with individual seeds.

These ladies were replanting the lawn with individual seeds. This is a huge sandstone wild boar– the third incarnation of the god, Shiva.

This is a huge sandstone wild boar– the third incarnation of the god, Shiva. And this is some of what’s carved into his side.

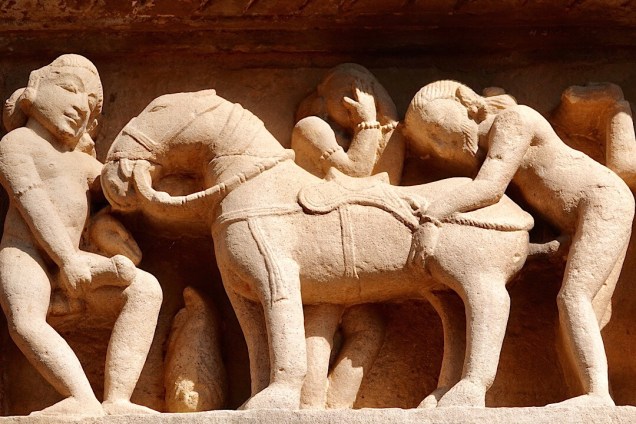

And this is some of what’s carved into his side. …wacky positions from the Kama Sutra, masturbation…

…wacky positions from the Kama Sutra, masturbation… …but it feels like every other aspect of human life is also captured. Soldiers slaughter each other with the aid of war elephants. A famous carving depicts a young woman applying her eye make-up.

…but it feels like every other aspect of human life is also captured. Soldiers slaughter each other with the aid of war elephants. A famous carving depicts a young woman applying her eye make-up. Another girl extracts a thorn from her foot:

Another girl extracts a thorn from her foot: People bathe, stretch, drink together…

People bathe, stretch, drink together… …listen to music.

…listen to music. The carvers’ sense of humor is obvious. In one of the most infamous scenes, a man is fornicating with a horse, while two men on each side await their turn. A third covers his eyes in disgust at the barbarism — except that the carver makes it clear he’s peeking.

The carvers’ sense of humor is obvious. In one of the most infamous scenes, a man is fornicating with a horse, while two men on each side await their turn. A third covers his eyes in disgust at the barbarism — except that the carver makes it clear he’s peeking.

The elephant looks like he’s got a sense of humor too.

The elephant looks like he’s got a sense of humor too. Some of the Jain monks never wear clothes. Like this one. Outside of the four-month-long monsoon season, where they congregate in some location (e.g. Khajuraho this year), the Jain monks wander naked through the countryside, praying and preaching and meditating.

Some of the Jain monks never wear clothes. Like this one. Outside of the four-month-long monsoon season, where they congregate in some location (e.g. Khajuraho this year), the Jain monks wander naked through the countryside, praying and preaching and meditating. One of their only possessions is the brush they carry to sweep insects out of their path to avoiding injuring them.

One of their only possessions is the brush they carry to sweep insects out of their path to avoiding injuring them. The city isn’t crowded, and there’s little traffic, so it feels quiet. A few temples are located in the surrounding farmland, and we cycled past folks drawing water from a well….

The city isn’t crowded, and there’s little traffic, so it feels quiet. A few temples are located in the surrounding farmland, and we cycled past folks drawing water from a well…. ..and kids swimming and bathing in a local stream.

..and kids swimming and bathing in a local stream. We pedaled through a village where a woman was slamming handfuls of cow dung on the facade of her house (home maintenance? We weren’t sure.)

We pedaled through a village where a woman was slamming handfuls of cow dung on the facade of her house (home maintenance? We weren’t sure.) I think it’s the only glimpse we’ll get of rural life in the heart of India. I’ll probably remember it as clearly as the riotous, naughty temple stone tapestry. But we’ve left it behind us now. I’m writing this on a train heading for the heart of Indian tourism. With luck, I’ll post it from our home stay in Agra, about a ten-minute walk from the Taj Mahal.

I think it’s the only glimpse we’ll get of rural life in the heart of India. I’ll probably remember it as clearly as the riotous, naughty temple stone tapestry. But we’ve left it behind us now. I’m writing this on a train heading for the heart of Indian tourism. With luck, I’ll post it from our home stay in Agra, about a ten-minute walk from the Taj Mahal. My photo doesn’t do it justice. It doesn’t clearly show all the small boats congregated in front of the seven platforms or the priest standing on each platform, and of course you can’t hear the continuous bells and the plaintive singing. Every night in Varanasi after sunset, before a vast assembly, the priests go through a complex ritual: blowing into conch shells, wafting incense dispensers, waving great silver candelabras. It’s part religious ceremony; part performance art.

My photo doesn’t do it justice. It doesn’t clearly show all the small boats congregated in front of the seven platforms or the priest standing on each platform, and of course you can’t hear the continuous bells and the plaintive singing. Every night in Varanasi after sunset, before a vast assembly, the priests go through a complex ritual: blowing into conch shells, wafting incense dispensers, waving great silver candelabras. It’s part religious ceremony; part performance art.

Strolling along these “ghats,” as they’re called, is endlessly entertaining. I’ve never felt more like I was on another planet. You see…

Strolling along these “ghats,” as they’re called, is endlessly entertaining. I’ve never felt more like I was on another planet. You see…

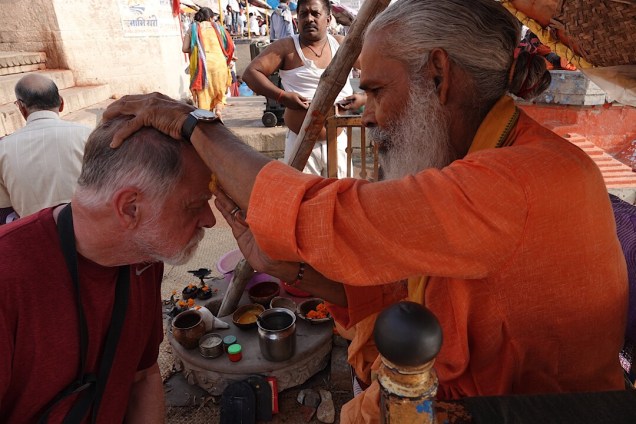

…holy men…

…holy men… …some of whom will bless you. There are…

…some of whom will bless you. There are… …ladies in saris tidying up…

…ladies in saris tidying up… …kids playing street hockey…

…kids playing street hockey… …pilgrims bathing….

…pilgrims bathing…. ..and shopping. These are sealed bottles of Ganga water, ready to take home for your friends. (To our friends, sorry. We resisted.)

..and shopping. These are sealed bottles of Ganga water, ready to take home for your friends. (To our friends, sorry. We resisted.) That’s not a typo. It was sunrise, not sunset. Varanasi’s air appears no cleaner than Kolkata’s.

That’s not a typo. It was sunrise, not sunset. Varanasi’s air appears no cleaner than Kolkata’s. To our surprise, we smelled no ugly odors.

To our surprise, we smelled no ugly odors. This is because the fires burn deodorizing banyan tree wood mixed with sandalwood, we were told.

This is because the fires burn deodorizing banyan tree wood mixed with sandalwood, we were told.

…and carefully weighed for each funeral pyre.

…and carefully weighed for each funeral pyre. The other two nights we spent in a guesthouse that cost $14 a night. Compared to the palace, it was spartan. The rooms were spotless, but tiny. And the 31-year-old owner/operator was smart and knowledgeable and generous-hearted. When he unintentionally dropped and lost one of the paper clips we kept in our passports to mark the page with the Indian visa (which every hotel must photocopy!), we told him it was no big deal. But two days later he presented us with a replacement that he went out and bought for us. After we checked out to move to the palace, he invited us to return for his special spiced tea (masala chai). In the conversation we had while sipping it, he felt like a treasured old friend.

The other two nights we spent in a guesthouse that cost $14 a night. Compared to the palace, it was spartan. The rooms were spotless, but tiny. And the 31-year-old owner/operator was smart and knowledgeable and generous-hearted. When he unintentionally dropped and lost one of the paper clips we kept in our passports to mark the page with the Indian visa (which every hotel must photocopy!), we told him it was no big deal. But two days later he presented us with a replacement that he went out and bought for us. After we checked out to move to the palace, he invited us to return for his special spiced tea (masala chai). In the conversation we had while sipping it, he felt like a treasured old friend. Steve and I sensed a peacefulness on the ghats of Varanasi, and Sonu said he feels it too. As hard as he works and as crazy as the guesthouse operation can get, he told us he tries to spend an hour or so by the river every day. It re-energizes him. I think there’s also beauty there which you can’t miss seeing.

Steve and I sensed a peacefulness on the ghats of Varanasi, and Sonu said he feels it too. As hard as he works and as crazy as the guesthouse operation can get, he told us he tries to spend an hour or so by the river every day. It re-energizes him. I think there’s also beauty there which you can’t miss seeing.