Someone might ask me: why would you take public buses to travel between cities in Guatemala? I might respond: why not?

Someone might ask me: why would you take public buses to travel between cities in Guatemala? I might respond: why not?

Here are the reasons Steve and I used buses to get from Rio Dulce to Tikal. (We wanted to go to Tikal because it’s the site of fabulous Mayan ruins that rank among the most famous touristic destinations in Guatemala.)

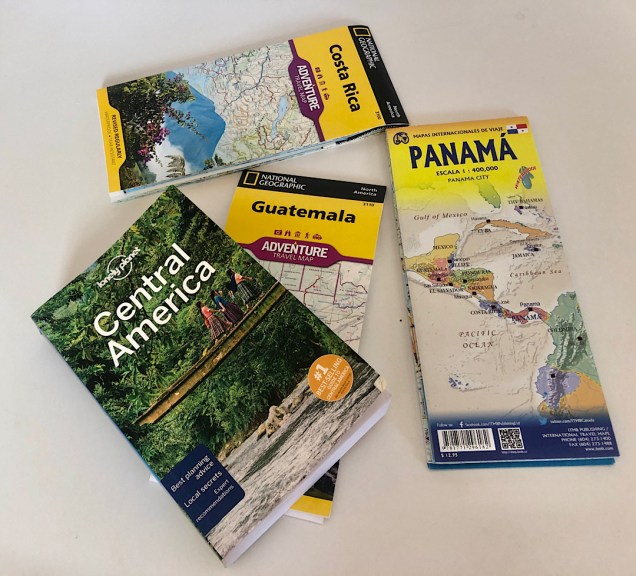

1) Buses are one of the only ways to get between those two places. One alternative might have been to rent a car on our arrival last week and drive ourselves everywhere. But stories about the crazy Guatemalan drivers and difficult urban traffic scared us. The second alternative was to hire a private driver, as we did to get to the quetzal reserve and Rio Dulce (and will do again later in the trip). That’s the easy choice, but it’s also invariably expensive. No trains or planes or boats connect Rio Dulce and Tikal, so they’re not alternatives.

2) Buses are how ordinary Guatemalans get around.

3) Buses are not expensive. That’s why regular folks use them.

Here are the reasons we might have flatly rejected bus travel.

1) It’s invariably tricky to figure out. It’s not a big deal if you’re a native or you speak the local language like one. But I have often found bus schedules to be daunting.

2) On buses, things often go wrong, sometimes in smaller ways (they break down), sometimes spectacularly. (Their brakes fail and they go off a cliff and everyone on them dies.)

When I knew we wanted to get from Rio Dulce to Tikal, I emailed Wilmer, the manager at the Tortugal. He said our choices were buses or a private driver, and he promised to help us arrange something after we arrived.

Wilmer was great. When we checked in, he said he could help us secure a private driver or he could guide us to a public bus that would take us to Santa Elena. From Santa Elena we would have to catch a chicken bus that would take us the additional 90 minutes to Tikal. (That’s a chicken bus pictured at the top of this post.) But he also had a friend who operated a chicken bus directly to Tikal. He said he would find out if that would be running.

As things turned out, the friend only took groups of 6 or larger, and Steve and I were the only people interested in going on Monday. With the promise of Wilmer’s help, we chose the other option: travel like most Guatemalans do.

Monday morning he took us in the launch to the town of Rio Dulce, then walked with us to the station where we bought tickets on a direct bus to Santa Elena. They cost $300 quetzals (about $39) for the two of us. I was happy to hear the guy behind the counter say the ride would take four hours (I had thought it might be closer to 6).

Less encouraging was that the next bus was expected between 9:30 and 10:30 (we had arrived at 8:30, hoping to catch what we thought would be a 9 am bus.) But we had plenty of electronic toys to entertain us and the tiny bus station was air conditioned, so we settled in for as long as it would take.

Siting there, I could summon few memories of uneventful bus rides in my life. I’ve had some, but I don’t remember anything about them. I usually don’t remember the traumatic rides either, but while waiting for the bus to Tikal, images flooded out of the part of my brain where I had repressed them. How could I have forgotten the Peruvian bus that broke down near the border of Bolivia, and the hours-long drama that followed, in which dozens of locals struggled to fix it? Or getting stuck on our “deluxe” bus in Colombia’s steam-bath heat, and having to ultimately transfer to a very much non-deluxe replacement? Or the homicidal Vietnamese bus driver who seemed intent on taking us to meet our maker? Along with thoughts of all those breakdowns and missed stops and awful delays, the thought also came back (duh!): when you’re on a Latin American bus, you are stripped of any illusion of control over your destiny (unless you believe in prayer.)

Miraculously, the bus did arrive at 9:30, and my refresher course in Bus Facts of Life continued.

Lesson One: The locals will always know what’s happening earlier than you do, and they will mobilize faster. That’s why you will get the last seats on the bus. Forget about sitting together.

Lesson Two: The concept of personal aural space does not exist. That’s why the 16-year-old guy next to you is uninhibited about broadcasting his favorite tunes from his phone. It’s why the six-year-old across the aisle blasts video games on his tablet and neither of the women flanking him tells him to tone it down.

Lesson Three: The bus will stop at random intervals and often it will be impossible to figure out why. On our trip, a guy in uniform boarded at one point and asked for IDs. I showed him an expired California driver’s license and he barely glanced at it. He didn’t demand anything of Steve (but Steve was wedged against the window in the row behind me, next to four Guatemalan guys.)

If it sounds like I’m complaining, I’m not. Nothing went wrong. We arrived at the Santa Elena bus terminal around 1:15 — 15 minutes before the ticket seller in Rio Dulce had said we would. A gaggle of men surrounded the bus when we disembarked, and I was braced to be hassled. Instead, when I said we wanted to get to Tikal, a brisk energetic guy led us to an office inside the large, clean terminal.

The man at the desk inside said he could sell us tickets ($19.50 for the two of us) on the only ride going directly to Tikal. It would be leaving in about an hour, he declared, which gave us time to eat the sandwiches Wilmer had packed for us.

Our ride arrived a few minutes late, and it turned out to be a van. Wilmer had said it would be a “chicken bus,” a Guatemalan institution. I had read that they are colorfully decorated former school buses that acquired new life here. They pick up and drop off passengers along certain routes. But a couple of guys on the van told me that at least in this part of Guatemala, a van could also earn the name just from the fact that stops on demand for passengers.

Wilmer had said it would be a “chicken bus,” a Guatemalan institution. I had read that they are colorfully decorated former school buses that acquired new life here. They pick up and drop off passengers along certain routes. But a couple of guys on the van told me that at least in this part of Guatemala, a van could also earn the name just from the fact that stops on demand for passengers.

Whatever you called it, that thing was an oven. By the time we stopped picking up riders, every seat was filled.

No one had to stand, and no one brought their chickens or any other animals on board. We reached Tikal a little after 4, very close to the time it was supposed to get there. We had reconnected with the everyday experience of locals, something both Steve and I cherish. We felt happy.

The next afternoon, after a mind-blowing experience in Tikal, we got a ride in a private car back to the airport In Santa Elena (aka Flores). In advance we had bought tickets on an airline called Transportes Aereos Guatemaltecas — everyone calls it TAG. If the weather had been good, I would have forgotten that leg of our journey instantly. Instead, when the driver dropped us off, storm clouds were gathering. The TAG employee at the check-in desk told us the flight was unfortunately delayed. It might be an hour late. Or maybe later. To pass the time, Steve and I made our way to a nearby snack shop. We each ordered beers and tamales (highly recommended by our driver/guide).. Not long after consuming them, peals of thunder and lightning ushered in a downpour so intense it seemed capable of breaching the roof and flooding all the indoor spaces.

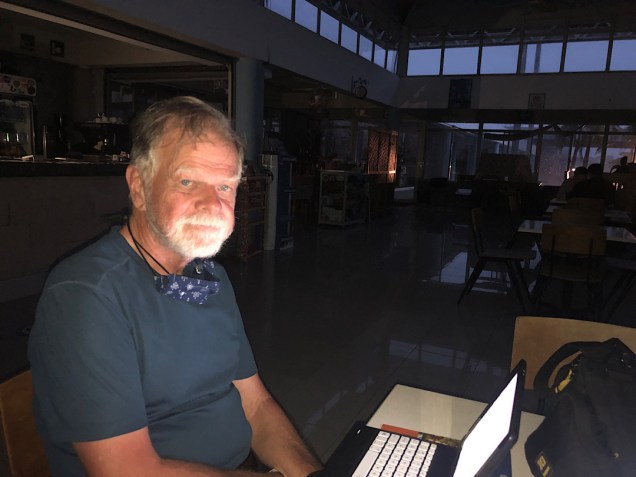

We waited, but no announcements came. Instead the lights went out. Phones and computer screens and blasts of lightning illuminated the faces of the few other sad travelers around us. Thunder made our ears ring. The lights came on eventually, but only for a while. Again we plunged abruptly into darkness.

But they came on again, and about 7:45, a propeller plane landed. Lightning was still splintering the sky when about 20 of us climbed aboard. Ironically, the 45-minute flight to Guatemala City was not terribly bumpy. Some rides are worst in anticipation.

Ironically, the 45-minute flight to Guatemala City was not terribly bumpy. Some rides are worst in anticipation.

the sterns of the sailboats and cruisers lined up along the docks bore place names like Oakland and Alameda, California and Houston, Texas.

the sterns of the sailboats and cruisers lined up along the docks bore place names like Oakland and Alameda, California and Houston, Texas. They looked like nice yachts, but I was happier ensconced in La Casita Elegante.

They looked like nice yachts, but I was happier ensconced in La Casita Elegante. Located at the farthest reach of the property, it was more rustico than elegante, but I loved the wild jungle surrounding the back of it.

Located at the farthest reach of the property, it was more rustico than elegante, but I loved the wild jungle surrounding the back of it.  In the other direction, we enjoyed views of the river. And the dining room came equipped with two friendly young Guatemalan dogs.

In the other direction, we enjoyed views of the river. And the dining room came equipped with two friendly young Guatemalan dogs.

A bit further downstream, we stopped at a bankside establishment that was part restaurant, part tourist attraction. Steve and I each paid 15 quetzals (about $2) to the 67-year-old proprietor, Felix,

A bit further downstream, we stopped at a bankside establishment that was part restaurant, part tourist attraction. Steve and I each paid 15 quetzals (about $2) to the 67-year-old proprietor, Felix, and he guided us up and down a plunging path to a creepy cave and natural sauna warmed by hot springs.

and he guided us up and down a plunging path to a creepy cave and natural sauna warmed by hot springs.

Steve and I have spent so much time in poor African villages in the last ten years, the Garifuna district almost felt like home. It was wretchedly poor. Most of the folks we passed looked tired.

Steve and I have spent so much time in poor African villages in the last ten years, the Garifuna district almost felt like home. It was wretchedly poor. Most of the folks we passed looked tired.

They were like the fancy mansions we passed on our drive with Alfredo, conspicuous, almost arrogant, in their wealth.

They were like the fancy mansions we passed on our drive with Alfredo, conspicuous, almost arrogant, in their wealth.

I like beautiful birds as much as the next person, but I’m no serious birdwatcher. I would have said spotting any particular bird would never shape the itinerary of any of my trips. Still, I knew that resplendent quetzals, gorgeous and elusive birds laden with powerful symbolism, are an icon in this part of the world. When border politics forced us to cut Belize from our journey and gave us three extra days in Guatemala, we decided to try to (metaphorically) bag this mystical avian.

I like beautiful birds as much as the next person, but I’m no serious birdwatcher. I would have said spotting any particular bird would never shape the itinerary of any of my trips. Still, I knew that resplendent quetzals, gorgeous and elusive birds laden with powerful symbolism, are an icon in this part of the world. When border politics forced us to cut Belize from our journey and gave us three extra days in Guatemala, we decided to try to (metaphorically) bag this mystical avian.

The trees protected us from the brunt of the rain, though droplets hitting leaves sounded like birds; they made me jump and crane my neck almost constantly, hoping to glimpse our quarry.

The trees protected us from the brunt of the rain, though droplets hitting leaves sounded like birds; they made me jump and crane my neck almost constantly, hoping to glimpse our quarry. But back at the Ranchitos, the manager told us to be on the porch at 5:30 the next morning, “and you will see a quetzal.”

But back at the Ranchitos, the manager told us to be on the porch at 5:30 the next morning, “and you will see a quetzal.” We admired the big violet saber-winged hummingbirds whom we’d been seeing throughout our stay.

We admired the big violet saber-winged hummingbirds whom we’d been seeing throughout our stay.  We milled about and didn’t chat much.

We milled about and didn’t chat much. But then the creature flew to another perch.

But then the creature flew to another perch.  I stared at that tail and the manager yelled. The steely early morning light made it hard to make out the bird’s brilliant red chest, but the tail looked like nothing I’d ever seen on a bird before: unmistakably a quetzal, Alfredo and the manager concurred.

I stared at that tail and the manager yelled. The steely early morning light made it hard to make out the bird’s brilliant red chest, but the tail looked like nothing I’d ever seen on a bird before: unmistakably a quetzal, Alfredo and the manager concurred.

He gave us boarding passes that let us go first through the jetway,

He gave us boarding passes that let us go first through the jetway, so we had tons of room, sitting in the first row. I Stayed in a perfect Down position when the flight attendant gave her speech,

so we had tons of room, sitting in the first row. I Stayed in a perfect Down position when the flight attendant gave her speech,  and although I got a little nervous during the take-off (and later, the landing), my p/M gave me the Lap command and let me look out the window. I found the sights out the window intriguing, if slightly creepy.

and although I got a little nervous during the take-off (and later, the landing), my p/M gave me the Lap command and let me look out the window. I found the sights out the window intriguing, if slightly creepy. Just as often, I napped.

Just as often, I napped.

Frankly, I’m not a fan.

Frankly, I’m not a fan. And pretty soon the sun was shining again.

And pretty soon the sun was shining again.

The coastal vistas were as beautiful and empty as any I’ve seen anywhere.

The coastal vistas were as beautiful and empty as any I’ve seen anywhere.

Then there’s the weather — gray, sodden, and dreary for much of the year. In the height of summer, we enjoyed some sunny spells, but the daytime highs rarely surpassed 60. Nights, the temperatures dipped into the 40s.

Then there’s the weather — gray, sodden, and dreary for much of the year. In the height of summer, we enjoyed some sunny spells, but the daytime highs rarely surpassed 60. Nights, the temperatures dipped into the 40s.

The path ahead of us invariably looked shorter than the trees were tall. The scented air invigorated me, and the sculpted shapes surrounding us often stopped us in our tracks.

The path ahead of us invariably looked shorter than the trees were tall. The scented air invigorated me, and the sculpted shapes surrounding us often stopped us in our tracks.

It’s a landscape that competes with the most breathtaking anywhere, I think, and yet it rarely shows up on lists of the natural wonders of the world.

It’s a landscape that competes with the most breathtaking anywhere, I think, and yet it rarely shows up on lists of the natural wonders of the world.

We spent an afternoon exploring a canyon whose walls are coated with ferns.

We spent an afternoon exploring a canyon whose walls are coated with ferns.  We got close to wild elk.

We got close to wild elk.  Another morning we hiked up the mouth of the Big River.

Another morning we hiked up the mouth of the Big River. We resisted paying to drive through one of the touristic tree wonders.

We resisted paying to drive through one of the touristic tree wonders. But we drove the Avenue of the Giants, where the huge trees crowd so close to the road people put reflectors on them as a warning.

But we drove the Avenue of the Giants, where the huge trees crowd so close to the road people put reflectors on them as a warning.

…until we crossed the Golden Gate Bridge and were back in Civilization. We slept in Santa Cruz last night and will spend our final night on the road in Santa Barbara. All that will be anticlimactic. Those hikes through the otherworldly, timeless woods were the climax.

…until we crossed the Golden Gate Bridge and were back in Civilization. We slept in Santa Cruz last night and will spend our final night on the road in Santa Barbara. All that will be anticlimactic. Those hikes through the otherworldly, timeless woods were the climax. This summer marks my 30th anniversary as a home-exchanger. It was 30 years ago that Steve and I first traded our house in San Diego, that time for a spacious ground-floor apartment in a cool stone building in the most chic neighborhood in Paris. It had a private garden that opened onto a larger shared green space. After that we were hooked. Since then we’ve done almost 20 exchanges all over the planet.

This summer marks my 30th anniversary as a home-exchanger. It was 30 years ago that Steve and I first traded our house in San Diego, that time for a spacious ground-floor apartment in a cool stone building in the most chic neighborhood in Paris. It had a private garden that opened onto a larger shared green space. After that we were hooked. Since then we’ve done almost 20 exchanges all over the planet.

It’s a magical place filled with oak trees…

It’s a magical place filled with oak trees…

manzanita…

manzanita… …and other native flora. Near the house, we can there’s a pond ringed with emerald grass.

…and other native flora. Near the house, we can there’s a pond ringed with emerald grass.

On the afternoons when we decided not to venture out, we’ve hung out in the sprawling, baronial manor house. A swamp cooler protects the interior from the heat. (To my surprise, this system works as well as any air-conditioning unit and apparently costs a fraction of the price to run.)

On the afternoons when we decided not to venture out, we’ve hung out in the sprawling, baronial manor house. A swamp cooler protects the interior from the heat. (To my surprise, this system works as well as any air-conditioning unit and apparently costs a fraction of the price to run.)

Except that there’s an entrance booth manned by a state historic park ranger…

Except that there’s an entrance booth manned by a state historic park ranger…

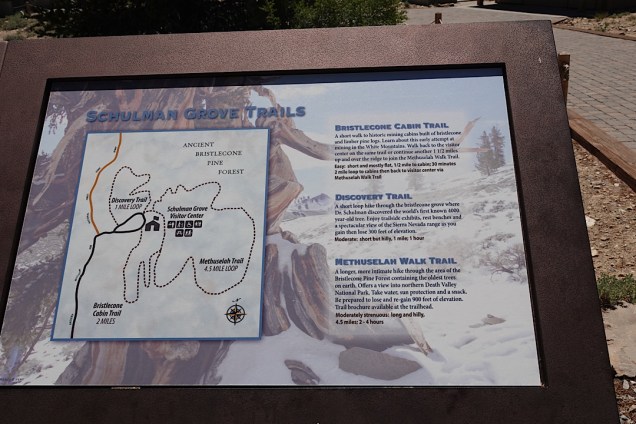

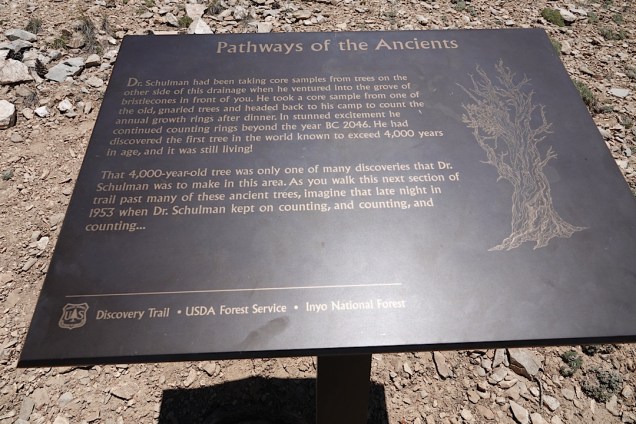

We chose the mile-long Discovery Trail. It led us to the section where in 1953 a dendrochronologist named Avery Schulman learned one night that he had just cut a core out of a tree whose rings indicated it was more than 4000 years old.

We chose the mile-long Discovery Trail. It led us to the section where in 1953 a dendrochronologist named Avery Schulman learned one night that he had just cut a core out of a tree whose rings indicated it was more than 4000 years old.

Over the millennia the bristlecone pine wood twists into weird sinuous forms, many of which are bare of vegetation.

Over the millennia the bristlecone pine wood twists into weird sinuous forms, many of which are bare of vegetation.

But green branches cluster low to the ground. They make it clear that, though the trees may look half dead, they’re still very much alive. When Nero was burning Rome, some of these very specimens were already more than two thousand years old.

But green branches cluster low to the ground. They make it clear that, though the trees may look half dead, they’re still very much alive. When Nero was burning Rome, some of these very specimens were already more than two thousand years old. I’m not a wildlife expert, and maybe even the experts don’t know what the future holds for bonobos. But what I want to say is: after visiting the Congo, I feel optimistic.

I’m not a wildlife expert, and maybe even the experts don’t know what the future holds for bonobos. But what I want to say is: after visiting the Congo, I feel optimistic. Suzy Kwetuenda at Lola ya Bonobo has spent countless hours talking to Congolese villagers in the rainforest about why bonobos deserve protection. She says some of them bristle at the notion of outsiders trying to stop them from eating their bush meat. But she retorts, “You know, we are lucky to be the only ones in the world to have bonobos! They are very precious. The BIG value of bonobos is not in your stomach! It’s very important to have bonobos for development. If you protect them, this area will have more and more visitors. They will come and help you!”

Suzy Kwetuenda at Lola ya Bonobo has spent countless hours talking to Congolese villagers in the rainforest about why bonobos deserve protection. She says some of them bristle at the notion of outsiders trying to stop them from eating their bush meat. But she retorts, “You know, we are lucky to be the only ones in the world to have bonobos! They are very precious. The BIG value of bonobos is not in your stomach! It’s very important to have bonobos for development. If you protect them, this area will have more and more visitors. They will come and help you!”