On our first-ever visit to Panama of course we would want to see the Panama Canal — vaunted 8th wonder of the world, 107-year-old shortcut between Earth’s two greatest oceans, Number Two on Lonely Planet’s “15 Top Panama Experiences.” And for Steve and me, experiencing the Canal had turned into something more; it had become a quest; a semi-sacred mission.

On our first-ever visit to Panama of course we would want to see the Panama Canal — vaunted 8th wonder of the world, 107-year-old shortcut between Earth’s two greatest oceans, Number Two on Lonely Planet’s “15 Top Panama Experiences.” And for Steve and me, experiencing the Canal had turned into something more; it had become a quest; a semi-sacred mission.

Weeks ago, in preparation for our travels, Steve began reading The Path Between the Seas, David McCullough’s splendid and definitive chronicle of what it took to create this engineering marvel. Steve immediately became besotted by it, declaring it was the best business story he had ever read. He couldn’t stop sharing the details with me and anyone else who would listen. I haven’t had time to read the book yet but I intend to. Listening to Steve convinced me I must.

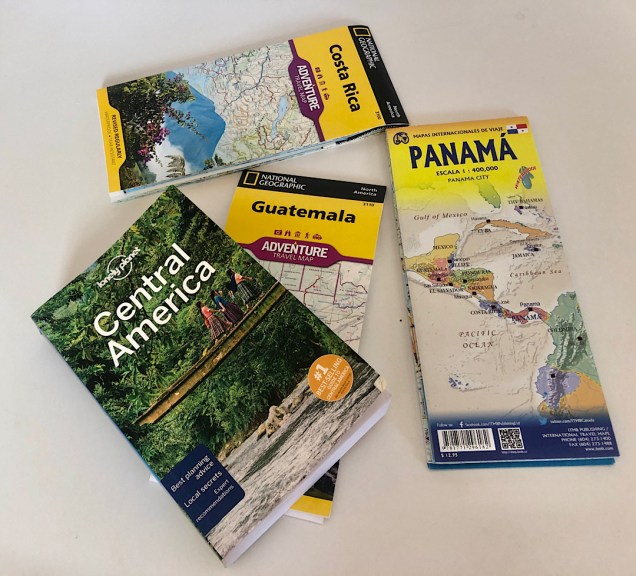

Our guidebook and various online authorities assured me there were many ways of seeing and learning about the canal. A museum in Panama City was dedicated to it. A highly recommended activity was to visit one of the lock sites; at least two (at both ends of the canal) had fancy visitor centers. We could ride in a historical passenger train that ran alongside the canal, or pay for a boat ride through all or part of it. I fretted we would have trouble fitting in all the options.

When I discovered there was a home-exchange option in Gamboa, I got more excited. Gamboa is a tiny hamlet situated about mid-way across the peninsula. When the United States built the canal, it received a strip of land five miles on either side of it which it was supposed to be owned by America “in perpetuity.” Jimmy Carter ultimately decided (correctly, Steve and I think) the Canal and the Zone would be better off in the hands of Panamanians. That changeover happened in 1999, but in the 1940s, the US military built housing for the American canal administrators in Gamboa, and it was one of these elegant buildings that Jorge L (a Panamanian) acquired and now uses as a weekend retreat. He also rents out the place via Airbnb and trades it on homeexchange.com, a site that lets you arrange direct house trades OR receive “Guest Points” for letting other folks stay in your home while you’re away. You can then “spend” those points to stay elsewhere.

I thus arranged for Steve and me to spend three nights at Jorge’s Gamboa house. We were a little nervous about landing at Panama City’s airport at 4:30 pm, picking up our rental car, and having to make the 45-minute drive with night approaching. But luck was with us, and we arrived in Gamboa under thick clouds around sunset. Jorge had only sent GPS coordinates for the center of the town plus a photo of his house (apparently addresses are not a thing in Panama.) We were feeling pretty irritable driving around the rapidly darkening streets, trying to figure out which dwelling place might belong to Jorge, when we spotted a guy watching us with apparent bemusement. This turned out to be Omar, a sort of caretaker who confirmed that we had reached our destination.

Jorge had never mentioned him. Omar let us in and it felt a bit like stepping into a time machine; I tried to conceal my mixed feelings.

Two stories tall, both levels of the house had high ceilings and a gracious layout. It appeared to be more or less clean, but any 70-plus-year-old building set on the edge of a steamy jungle is bound to look and feel a bit grimy. I wondered how many exotic spiders and snakes and centipedes might be staying there with us. Omar gave us vague directions to the only eatery in town, and somehow we made our way to it in what by then was complete darkness. My heart sank at the sight of the garishly lit storefront, open to the street, no customers evident.

A tiny grocery store run by a Vietnamese couple adjoined it, however, and we bought enough supplies to return to the house and throw together a pasta dinner. The house was sweltering, but a floor fan made it bearable. Still I felt beyond sticky, and my mood dipped further when we discovered the shower taps in the only full bathroom appeared to be rusted into inoperability. I WhatsApped Jorge but heard nothing from him that night.

In the morning, Jorge responded that he would have Omar check the shower, and when he appeared moments later Omar somehow muscled the taps into life. Steve brewed the ground Duran Cafe Puro (“Panama 1907”) that we had bought the night before into something that tasted actually delicious. I cracked four thick brown eggshells and scrambled the whites and deep orange yolks in melted butter. With sunshine streaming through the windows, the house looked substantially more charming; its character outweighing the mild grubbiness.

In high spirits, we set out for the Gamboa Rainforest Resort about 2 kilometers away. There we hoped to sign up for a tour or two and if necessary make a reservation for dinner in the fancy restaurant there.

In high spirits, we set out for the Gamboa Rainforest Resort about 2 kilometers away. There we hoped to sign up for a tour or two and if necessary make a reservation for dinner in the fancy restaurant there.

I had read (and Jorge had confirmed) that this $30 million, 5-star hotel complex could be enjoyed not just by guests but also day visitors like Steve and me. It was less than a mile and a half from Jorge’s. We drove and found the parking lot almost empty. Still the grandiose entryway gave no indication it was closed. We walked in and gaped at one of the strangest sights I’ve ever seen.

The lobby was enormous, immaculate, and elegant, and the views breathtaking.

But where were the people?

Slightly dazed, we wandered around for a while and spotted one distant gardener and one guy cleaning the pool. We thought we heard the voice of maids in one of the guest wings. But we detected no other sign of humans. Indeed it looked like aliens had just departed after herding everyone onto the spaceship.

Clearly, we wouldn’t be booking spots on the the 11 am Gamboa Tree Trek. Or any of the Gatun Lake Expedition boat rides. Still, Gamboa is situated on the Canal, so we left the resort and did some poking around the town and the banks of the famous waterway. Parts of the town also looked abandoned.

From the Puente de Gamboa, it would be easy to mistake the Canal for a workaday river. But Steve was all too keenly aware of what went into creating this portion of the waterway — the infamous Culebra Cut. The cut passes through Panama’s continental divide and the highest point on the canal route. It’s excavation bankrupted the French company that made the first attempt to dig an isthmian canal and cost the USA twice what was originally expected.

From the Puente de Gamboa, it would be easy to mistake the Canal for a workaday river. But Steve was all too keenly aware of what went into creating this portion of the waterway — the infamous Culebra Cut. The cut passes through Panama’s continental divide and the highest point on the canal route. It’s excavation bankrupted the French company that made the first attempt to dig an isthmian canal and cost the USA twice what was originally expected.

Steve was dying to get a better look at the Cut, so later that afternoon we drove across the snazzy Puente Centenario and caught this view. We also looked forward to our visit the next day to the Miraflores Locks near Panama City. Steve was understandably crushed when he checked for directions on Google Maps Wednesday night and read that the its visitor center was closed because of the pandemic.

We also looked forward to our visit the next day to the Miraflores Locks near Panama City. Steve was understandably crushed when he checked for directions on Google Maps Wednesday night and read that the its visitor center was closed because of the pandemic.

I double-checked and confirmed the closure. But I also saw that the Agua Clara Visitor Center, near Colon, had just re-opened to tourists on May 1. I had to make a reservation online, but almost all the slots were available.

When we arrived there Thursday morning, we learned that a big part of this center also was still closed (our entrance tickets were discounted, as a result.) But we were able to enter the huge, modern observation platform, where we watched a gigantic container ship from Hong Kong approach and enter the first of the three sets of locks that step boats down to the level of the Caribbean Sea.

These were the new locks opened in 2016, financed in part by Japanese and Europeans, that accommodate ships far larger than the original locks. Those are still operating, and about two dozen tankers and car carriers and smaller container vessels and other ships pass through each day. Although we couldn’t get close to the old locks, after we left Agua Clara we drove around some more and eventually found the nearby dam that created one of the essential components of the canal, Gatun Lake, at the time of its creation the largest man-made body of water in the world.

Making it all work in the face of unimaginable obstacles and challenges, “This was the greatest engineering effort in the history of mankind,” Steve declared. “Greater than the pyramids at Giza. Greater than landing a man on the moon.”

Friday we packed up and left Jorge’s place, happy in the end to have had our three nights there. (As it turned out, the only jungly creature who joined us was this two-inch-long lizard, who seemed to live in the kitchen.) We drove to Panama City, turned in our rental car, and took a taxi to The Sexiest Condo in Panama, which is how Vicki Marie S bills her unit on the 31st story of a high-rise overlooking Panama Bay. I used more of our home-exchange Guest Points to secure three nights for us here, and I have to say it is pretty sexy. Here’s the view of the city skyline from the balcony outside our bedroom with its king-sized bed.

We drove to Panama City, turned in our rental car, and took a taxi to The Sexiest Condo in Panama, which is how Vicki Marie S bills her unit on the 31st story of a high-rise overlooking Panama Bay. I used more of our home-exchange Guest Points to secure three nights for us here, and I have to say it is pretty sexy. Here’s the view of the city skyline from the balcony outside our bedroom with its king-sized bed. And the view of me wondering: how DOES one pole-dance, anyway?

And the view of me wondering: how DOES one pole-dance, anyway?

Our immersion in Panamanian Canal arcana wasn’t quite over. This morning (Saturday, May 29) we spent a couple of hours at the gleaming Panama Canal Museum in the gentrified Casco Viejo neighborhood.  If not great, it’s respectable, and I think at last Steve feels sated. We’ll have all day tomorrow to participate in the Sunday morning Ciclovia, visit the natural history museum housed in a particularly colorful Frank Gehry structure, and eat more of the excellent local fish. Probably it will all be fun. Still, I think we’ll depart for Costa Rica Monday most impressed by how much luck we had in understanding the greatest engineering achievement of all time.

If not great, it’s respectable, and I think at last Steve feels sated. We’ll have all day tomorrow to participate in the Sunday morning Ciclovia, visit the natural history museum housed in a particularly colorful Frank Gehry structure, and eat more of the excellent local fish. Probably it will all be fun. Still, I think we’ll depart for Costa Rica Monday most impressed by how much luck we had in understanding the greatest engineering achievement of all time.

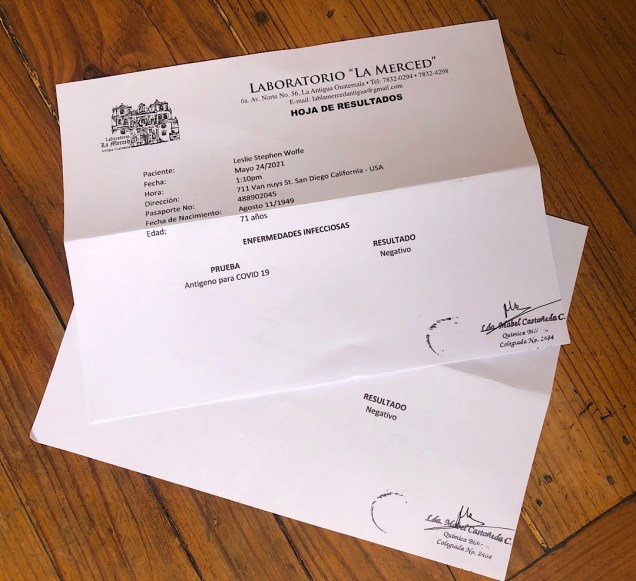

Monday morning promptly at 7, we walked the few blocks to the clinic. Iron bars blocked entrance into its unprepossessing foyer, and for a moment we wondered if it was closed. Then I noticed a cord attached to a bell behind the bars. I reached through and yanked. A moment later, the gate buzzed. We pushed our way in.

Monday morning promptly at 7, we walked the few blocks to the clinic. Iron bars blocked entrance into its unprepossessing foyer, and for a moment we wondered if it was closed. Then I noticed a cord attached to a bell behind the bars. I reached through and yanked. A moment later, the gate buzzed. We pushed our way in.

We were instructed to return in a half-hour for the results. We got coffee at a nearby cafe, then went back. Another tug on the bell; another confrontation with the inhospitable receptionist. She didn’t say a word but pulled out two pieces of paper and began folding them.

We were instructed to return in a half-hour for the results. We got coffee at a nearby cafe, then went back. Another tug on the bell; another confrontation with the inhospitable receptionist. She didn’t say a word but pulled out two pieces of paper and began folding them.

I first met the Mayans back in high school. I think I ran into them in my freshman-year world history course, though truth be told I remember nothing of whatever I learned. In my consciousness, they just became part of a jumble of Olmecs and Toltecs and other people who once rocked in Mesoamerica.

I first met the Mayans back in high school. I think I ran into them in my freshman-year world history course, though truth be told I remember nothing of whatever I learned. In my consciousness, they just became part of a jumble of Olmecs and Toltecs and other people who once rocked in Mesoamerica.

The Mayans developed an advanced (base 20) mathematical system, and a hieroglyphic writing system that compared to that of the Egyptians.

The Mayans developed an advanced (base 20) mathematical system, and a hieroglyphic writing system that compared to that of the Egyptians. Some of the writing has been deciphered from stone markers such as this one. But our guide said that sadly, only three of their books have survived. The Spaniards burned all the rest — reportedly 1200 in just one morning.

Some of the writing has been deciphered from stone markers such as this one. But our guide said that sadly, only three of their books have survived. The Spaniards burned all the rest — reportedly 1200 in just one morning.

At the foot of the public pier in the town of Panajachel, we caught a launch to our hotel, La Casa del Mundo. Built starting in 1980 by a Guatemalan woman, Rosy Valenzuela, and her American husband (Bill Fogarty), it’s one of the most remarkable places I’ve stayed anywhere. Every cottage built on the vertiginous stone cliff commands heart-stopping views.

At the foot of the public pier in the town of Panajachel, we caught a launch to our hotel, La Casa del Mundo. Built starting in 1980 by a Guatemalan woman, Rosy Valenzuela, and her American husband (Bill Fogarty), it’s one of the most remarkable places I’ve stayed anywhere. Every cottage built on the vertiginous stone cliff commands heart-stopping views.

Friday, Steve and I visited three of the villages situated on the lakeshore not far from La Casa. Our guide was Alex, 29 (whose Mayan name I forgot to write down.) He and his three siblings first learned Tzutujil, one of the 23 Mayan languages. But all his classes in school were taught in Spanish, by government mandate, so the Mayans are also fluent in that. About 5 years ago, when Alex decided to become a tour guide, he learned to speak English (well) in an intensive program in Guatemala City to which he got a scholarship. These days he’s studying Hebrew because so many Israelis come to Guatemala on vacation (and to start businesses, like this one).

Friday, Steve and I visited three of the villages situated on the lakeshore not far from La Casa. Our guide was Alex, 29 (whose Mayan name I forgot to write down.) He and his three siblings first learned Tzutujil, one of the 23 Mayan languages. But all his classes in school were taught in Spanish, by government mandate, so the Mayans are also fluent in that. About 5 years ago, when Alex decided to become a tour guide, he learned to speak English (well) in an intensive program in Guatemala City to which he got a scholarship. These days he’s studying Hebrew because so many Israelis come to Guatemala on vacation (and to start businesses, like this one).

Pulling off a chunk and removing the seeds from it…

Pulling off a chunk and removing the seeds from it… Beating the seedless chunk to make it smooth…

Beating the seedless chunk to make it smooth… Then using a hand-held spindle to twist the fiber into thread.

Then using a hand-held spindle to twist the fiber into thread.

This is what is looked like, in action:

This is what is looked like, in action:

Someone might ask me: why would you take public buses to travel between cities in Guatemala? I might respond: why not?

Someone might ask me: why would you take public buses to travel between cities in Guatemala? I might respond: why not?

Wilmer had said it would be a “chicken bus,” a Guatemalan institution. I had read that they are colorfully decorated former school buses that acquired new life here. They pick up and drop off passengers along certain routes. But a couple of guys on the van told me that at least in this part of Guatemala, a van could also earn the name just from the fact that stops on demand for passengers.

Wilmer had said it would be a “chicken bus,” a Guatemalan institution. I had read that they are colorfully decorated former school buses that acquired new life here. They pick up and drop off passengers along certain routes. But a couple of guys on the van told me that at least in this part of Guatemala, a van could also earn the name just from the fact that stops on demand for passengers.

Ironically, the 45-minute flight to Guatemala City was not terribly bumpy. Some rides are worst in anticipation.

Ironically, the 45-minute flight to Guatemala City was not terribly bumpy. Some rides are worst in anticipation. the sterns of the sailboats and cruisers lined up along the docks bore place names like Oakland and Alameda, California and Houston, Texas.

the sterns of the sailboats and cruisers lined up along the docks bore place names like Oakland and Alameda, California and Houston, Texas. They looked like nice yachts, but I was happier ensconced in La Casita Elegante.

They looked like nice yachts, but I was happier ensconced in La Casita Elegante. Located at the farthest reach of the property, it was more rustico than elegante, but I loved the wild jungle surrounding the back of it.

Located at the farthest reach of the property, it was more rustico than elegante, but I loved the wild jungle surrounding the back of it.  In the other direction, we enjoyed views of the river. And the dining room came equipped with two friendly young Guatemalan dogs.

In the other direction, we enjoyed views of the river. And the dining room came equipped with two friendly young Guatemalan dogs.

A bit further downstream, we stopped at a bankside establishment that was part restaurant, part tourist attraction. Steve and I each paid 15 quetzals (about $2) to the 67-year-old proprietor, Felix,

A bit further downstream, we stopped at a bankside establishment that was part restaurant, part tourist attraction. Steve and I each paid 15 quetzals (about $2) to the 67-year-old proprietor, Felix, and he guided us up and down a plunging path to a creepy cave and natural sauna warmed by hot springs.

and he guided us up and down a plunging path to a creepy cave and natural sauna warmed by hot springs.

Steve and I have spent so much time in poor African villages in the last ten years, the Garifuna district almost felt like home. It was wretchedly poor. Most of the folks we passed looked tired.

Steve and I have spent so much time in poor African villages in the last ten years, the Garifuna district almost felt like home. It was wretchedly poor. Most of the folks we passed looked tired.

They were like the fancy mansions we passed on our drive with Alfredo, conspicuous, almost arrogant, in their wealth.

They were like the fancy mansions we passed on our drive with Alfredo, conspicuous, almost arrogant, in their wealth.

I like beautiful birds as much as the next person, but I’m no serious birdwatcher. I would have said spotting any particular bird would never shape the itinerary of any of my trips. Still, I knew that resplendent quetzals, gorgeous and elusive birds laden with powerful symbolism, are an icon in this part of the world. When border politics forced us to cut Belize from our journey and gave us three extra days in Guatemala, we decided to try to (metaphorically) bag this mystical avian.

I like beautiful birds as much as the next person, but I’m no serious birdwatcher. I would have said spotting any particular bird would never shape the itinerary of any of my trips. Still, I knew that resplendent quetzals, gorgeous and elusive birds laden with powerful symbolism, are an icon in this part of the world. When border politics forced us to cut Belize from our journey and gave us three extra days in Guatemala, we decided to try to (metaphorically) bag this mystical avian.

The trees protected us from the brunt of the rain, though droplets hitting leaves sounded like birds; they made me jump and crane my neck almost constantly, hoping to glimpse our quarry.

The trees protected us from the brunt of the rain, though droplets hitting leaves sounded like birds; they made me jump and crane my neck almost constantly, hoping to glimpse our quarry. But back at the Ranchitos, the manager told us to be on the porch at 5:30 the next morning, “and you will see a quetzal.”

But back at the Ranchitos, the manager told us to be on the porch at 5:30 the next morning, “and you will see a quetzal.” We admired the big violet saber-winged hummingbirds whom we’d been seeing throughout our stay.

We admired the big violet saber-winged hummingbirds whom we’d been seeing throughout our stay.  We milled about and didn’t chat much.

We milled about and didn’t chat much. But then the creature flew to another perch.

But then the creature flew to another perch.  I stared at that tail and the manager yelled. The steely early morning light made it hard to make out the bird’s brilliant red chest, but the tail looked like nothing I’d ever seen on a bird before: unmistakably a quetzal, Alfredo and the manager concurred.

I stared at that tail and the manager yelled. The steely early morning light made it hard to make out the bird’s brilliant red chest, but the tail looked like nothing I’d ever seen on a bird before: unmistakably a quetzal, Alfredo and the manager concurred.