January 9, 2011

What an amazing series of contrasts this trip is providing us with! We’re halfway through the next installment, our four-day trek through the Ethiopian highlands. We’re using the services of a non-profit organization called TESFA which is dedicated to organizing touristic experiences that will benefit the local populations. The idea is to hike through the countryside, moving from one to another of ten camps in rural villages. The camps contain little huts (tukuls) made of rocks and a mixture of brown mud and straw (an African version of adobe) like those in which the locals live. So it’s an opportunity to meet people, while savoring the magnificent landscapes.

What an amazing series of contrasts this trip is providing us with! We’re halfway through the next installment, our four-day trek through the Ethiopian highlands. We’re using the services of a non-profit organization called TESFA which is dedicated to organizing touristic experiences that will benefit the local populations. The idea is to hike through the countryside, moving from one to another of ten camps in rural villages. The camps contain little huts (tukuls) made of rocks and a mixture of brown mud and straw (an African version of adobe) like those in which the locals live. So it’s an opportunity to meet people, while savoring the magnificent landscapes.

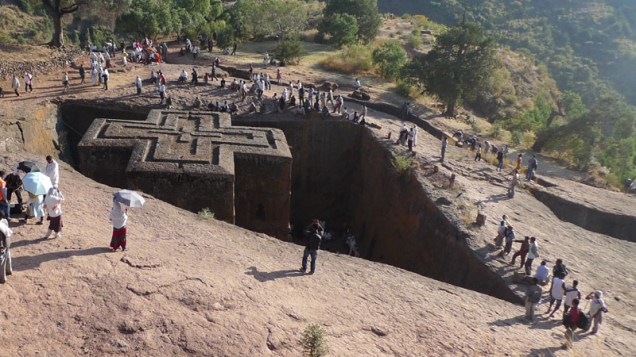

After the Christmas morning services in Lalibela, we ate breakfast and met our TESFA guide, Belay, and two fellow trekkers: a San Francisco photographer named David Page and his buddy Steve Maltby. We all loaded into a minivan for the two-hour drive to Gashena, breathing in more of the devilish dust and diesel fumes. Lunch, when we finally stopped, was injera and shiro — a bubbling pot of spiced garbanzo beans. Three ragged guys tied our bags onto a couple of doughty little donkeys.  Then we were off!

Then we were off!

It felt splendid to be walking in the quiet countryside, where the air was clean. For an hour or so, we hiked down rocky lanes past fields of newly sheared wheat, the grain-bearing stalks piled into huge stacks, awaiting threshing. Blue-gray eucalyptus has been planted extensively, replacing the stately junipers that once covered this land. Farmers plant the cuttings in a grid, as if they were broccoli seedlings, to be harvested later for firewood and building materials. They may not be native, but the eucs do contrast nicely with the ambers and browns of the farms. Parts of the rolling landscape made me think of a dryer version of southern France.

There’s nothing in France, however, to my knowledge, that resembles the landscape at the edge of the escarpment where our first camp was located. Just a few yards from the tukuls, the ground dropped away, revealing an enormous panorama that reminded us more than anything of the Grand Canyon, though the colors may have been a bit more muted. Another difference was the complex terracing cut into many hillsides and the grid of tiny farms lining much of the bottomland. But the scale was fantastic. Just as the rock churches would give Egypt’s tombs a run for the tourist traffic, if only more people knew about them, so these sights could compete with the canyonlands of the American West.

**************

Two more days have passed; I’m writing this from our tukul in our third and last campsite: Mequat Mariam. If anything, the vistas outside this one are more magnificent than the previous two, even vaster and wilder. To reach this site, we hiked for some 12 miles. As on the previous two days, the going has been more or less flat, though lots of it has required stepping carefully in boulder-strewn creekbeds. Altitudes have ranged between 8,500 and 9,000 feet.

At the rest stops along the way and in the camps at night, the food we’ve been served has been edible, if plain and vegetarian, and everywhere we’ve been offered good beer and excellent coffee (roasted on a tin griddle, ground with a mortar and pestle, and boiled in a pot, right before we’ve drunk it). No electric lines reach these villages, nor do any generators provide light in exchange for diesel. So when the sun has set, our world has been illuminated only by moonlight and candles and wood fires built by the camp staff. The women who cook do so squatting on the ground, while we’ve gathered around a larger fire, to drink our beers and swap our stories. The smoke from these indoor fires makes them a lot less pleasant than they would be outdoors. But on the whole, I’ve found this more pleasant than actual camping. The beds in our tukuls are comfortable (foam on concrete platforms), and I learned in the last camp that I was sleeping in the same bed that Brad Pitt occupied, when he visited here in 2004.

During the days, Steve and I both have savored the pleasant monotony of trekking. You get into a comforta ble rhythm, at times taking in your surroundings, at times chatting with your guide or fellow trekkers, at times simply concentrating on putting one foot carefully in front of the other, taking care not to twist an ankle. Interruptions in this simple routine stand out: coming upon tribes of gelada baboons raiding farmers’ fields (to munch the tasty grass roots) and being chased away by stone-throwing kids. Or watching, transfixed by the sight of men and boys threshing the wheat that we saw that first afternoon. They toss a bunch of it on the ground, then drive teams of 4 or 6 or 8 donkeys or horses or cows, tied together, over it in a circle, so th

ble rhythm, at times taking in your surroundings, at times chatting with your guide or fellow trekkers, at times simply concentrating on putting one foot carefully in front of the other, taking care not to twist an ankle. Interruptions in this simple routine stand out: coming upon tribes of gelada baboons raiding farmers’ fields (to munch the tasty grass roots) and being chased away by stone-throwing kids. Or watching, transfixed by the sight of men and boys threshing the wheat that we saw that first afternoon. They toss a bunch of it on the ground, then drive teams of 4 or 6 or 8 donkeys or horses or cows, tied together, over it in a circle, so th at their hooves will separate the wheat from the chaff.

at their hooves will separate the wheat from the chaff.

*******

January 11, 2012

Now the trek’s behind us. Our final hike this morning lasted about two and a half hours and took us from Mequat Marian to a field where a mini-bus awaited us, as pre-arranged. At one point, we passed men tooting horns made from goats and striking drums, and our guide explained that this was a new scheme: calling together the whole community (of men and boys, at least) to work on a communal project, one day per month. I thought I detected a festive air in some of the villagers, as they gathered. There might be work in store, but at least it was a break from the routine drudgery.

Piling into the vehicle, I couldn’t help thinking of the story we’d heard on our first full day from a young family from the Boston area: mom, dad, and two cute little girls, who’d hiked from the opposite direction. They described something that had happened to them on their way to Lalibela. The minivan in front of them hit and killed a 70-year-old man, a tragedy that could carry a sentence of up to 15 years for the guilty driver. The owner of van, who’d only had his driver’s license for two weeks, came to take over the driving, but he’d quickly developed a flat tire that he didn’t know how to fix. So, the couple told us, their driver had helped out and offered him their spare tire. A little further down the road, however, the van owner had lost control of his vehicle on a curve, going over the embankment and rolling it several times. Wearing the only seatbelt, the driver had walked away unscathed. But 4 of the 12 or so passengers died — one on the scene, another in the van, and at least a couple of others in the hospital in Lalibela.

Clearly, the Ethiopian roads hold many hazards, but we’ve dodged them all so far. Now we’re in the small city of Bahir Dar, looking forward to our boat ride to a monastery tomorrow.