The idea for this road trip was to see the great sights of the Southwest we’d somehow missed. To make our drive to Austin for the eclipse a kind of mop-up tour. We might undertake other road trips elsewhere sometime, but we could close the atlas on at least this quadrant of America.

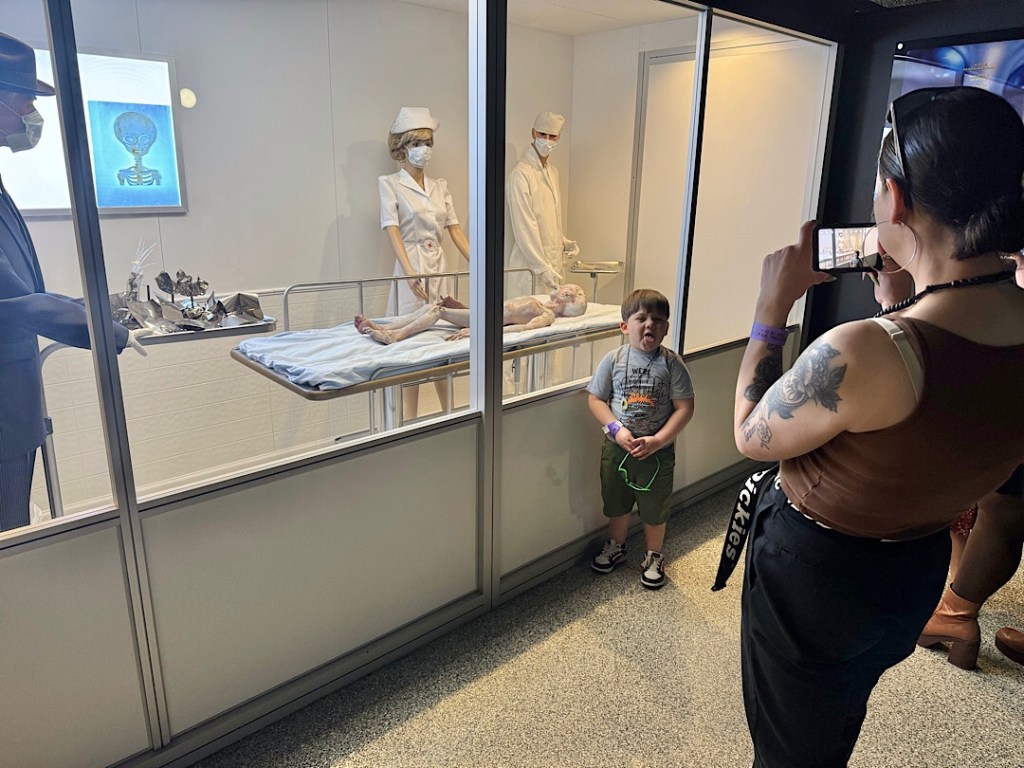

Nice try. Spending time in the ruins of Chaco Canyon (above) and among Sedona’s red rocks; jouncing through Canyon de Chelly and ogling fake aliens in Roswell all rewarded us richly (as I recorded in my earlier posts.) We also fared well on the drive back, even if White Sands National Park somewhat underwhelmed me.

In contrast, our morning in Carlsbad Canyon far exceeded my expectations.

What wrecked our “Adios, Southwest!” Plan was listening to the audio version of House of Rain, a kind of detective story written by a naturalist/adventurer/desert ecologist named Craig Childs. Driving east through the Indian reservations, we’d consumed a more classic mystery – one of the Hillerman stories starring Navajo tribal police officers. But I had also downloaded House of Rain hoping finally to learn about the Anasazi people (aka Ancient Puebloans). I knew vaguely they had lived in cliff dwellings in the area where Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah come together. The subject of House of Rain was who they were and what became of them – just what I wanted to know.

Visiting the Heard Museum in Phoenix and Flagstaff’s Museum of Northern Arizona and Canyon de Chelly and Chaco gave us droplets of the answer. But listening to Childs on the drive home was like jumping into a roaring flood.

He starts with Chaco. We’d just been there – barely a week before, and yeah, the scale and the height of its elaborate complexes had impressed us. But Childs is as familiar with the place as if he’d grown up there, and he made it come alive, explaining what it must have been like when under construction, more than a thousand years ago. He communicates the wonderment of what these folks accomplished, chopping down trees from forests more than 50 miles away and erecting buildings that remained the tallest in North America until skyscrapers began to sprout in Chicago. Then they built a dazzling network of roads radiating out from the heart of it, and they communicated over long distances with a complex signaling system. All these things happened at a time and place that in my mind had always been just…. blank. Childs filled it.

The Anasazi disappeared from Chaco around 1200 A.D., and what happened to them is the mystery explored by the book. It’s a dense, complex story I’m glad I listened to for all those hours – reading it on paper would have been daunting. I won’t try to summarize, just say that what Steve and I heard made us marvel at our ignorance and stoked a curiosity to see more: Mesa Verde or Aztec Ruins or the pueblos where the Anasazis’ descendants still live today.

Will we get there? Not soon. In less than a month, we’ll fly to Miami, a launching point for a visit to a region Steve has begun referring to as Ground Zero for Where All the Trouble in North America Began: the Caribbean. Our plan is to spend time staying mostly in exchange houses and Airbnbs on Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Jamaica. Stay tuned for details of how that one works out.