January 8, 2012

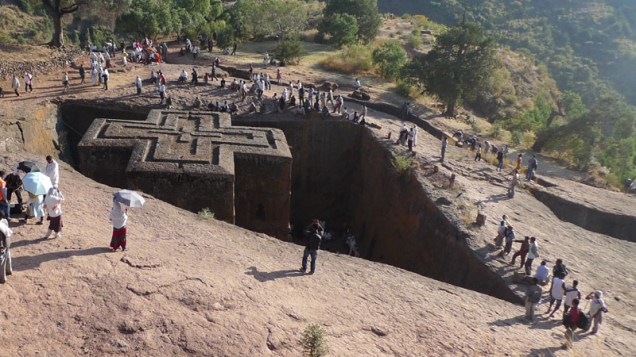

Both the Lonely Planet and Bradt guides to Ethiopia agree: if there is one thing no visitor to Ethiopia should miss, it’s Lalibela. Now that we’ve spent the last two days here, I have to concur: this place is amazing. It is the town where, sometime in the 1100s, a Christian Ethiopian king conceived of creating a “new Jerusalem” in the rugged, dry highlands. To that end, he assembled a crew of master stone carvers and other artisans and had them chisel 11 churches out of the basalt, underfoot. In essence, they sculpted these large and richly ornamented structures out of the rocky ground.

What I can only imagine is what it must be like to visit Lalibela under normal circumstances. The town’s population is somewhere around 30,000 people. Almost inaccessible for most of its history, it still isn’t easy to get to. One or two flights come in per day, but none of the roads here is paved, and the drive to or from Addis takes two long, hard days.

Every Christmas (which comes about two weeks later than our Western one), however, something like 200,000 religious pilgrims make the town their destination. This year Steve and I were among them. Being here to witness their celebrations transformed the experience, making the stunning otherworldly stone churches merely the setting for the spectacle unfolding in and around them .

.

The bus that took us from the airport to our hotel nosed its way through a dense throng of men, women, and children heading to the market. Lalibela’s weekly market always takes place on Saturday, but this one was special, because of the holiday. Most people carried their sales goods tied up in cloth bundles, but some drove goats or sheep or cattle or donkeys; some bore crates of potatoes on their heads. If we had traveled back in time to the stone age in the Omo Valley, here we had moved up to a medieval world.

From our hotel room, the Alief Paradise, floor-to-ceiling windows and a little balcony offered us views of the market teaming in the distance. But the churches called us, and we quickly found a guide who also happened to be a deacon for the monolithic church known as the House of Mary. Daniel lacked Endalk’s charm and command of English, but he knew his churches. He hired us a shoe man, who for the stratospherically high holiday price of 100 birr ($6) would guard our shoes every time we entered a church and help us quickly get back into them. Then Daniel led us through the churches as best as possible, explaining the complex symbolism of the paintings and architectural elements and helping us to thread our way through the crowds of pilgrims who jammed every corridor and every chamber. Neither Steve nor I are particularly claustrophobic; only at the underground passage known to the faithful as Purgatory, did we demur. It looked to be little more than shoulder wide, and jammed solid with human bodies.

I’m writing this now on Sunday morning, and having spent almost two days among the pilgrims, I’ve come to admire their astounding s trength. Most have walked for days or weeks to be here, surviving on scraps of food and questionable water. They wear long white robes, and I’m mystified by how clean they look, since they’re sleeping in the open air on mats spread over the rocky ground, peeing in bushes and against fences, and defecating God knows where. For all these trials, for all the staggering crowds here, most seem patient and good-humored and even solicitous of the oddball ferengis among them. We’ve seen countless clusters of them singing, dancing, clapping, ululating; they believe that having made it to Lalibela, they’ve secured themselves eternal happiness af

trength. Most have walked for days or weeks to be here, surviving on scraps of food and questionable water. They wear long white robes, and I’m mystified by how clean they look, since they’re sleeping in the open air on mats spread over the rocky ground, peeing in bushes and against fences, and defecating God knows where. For all these trials, for all the staggering crowds here, most seem patient and good-humored and even solicitous of the oddball ferengis among them. We’ve seen countless clusters of them singing, dancing, clapping, ululating; they believe that having made it to Lalibela, they’ve secured themselves eternal happiness af ter death.

ter death.

The priests and deacons — hundreds of them — look successful too. Older ones wear sumptuous robes and, sometimes bejeweled headpieces. The oldest could be African incarnations of Santa — fat black men with huge black beards, wearing huge gold crosses and hats shaped like monstrous mushrooms. We’d heard there would be a procession of priests through the town, but we could find no sign of it Friday night (the night Endalk and other folks had told us was Christmas Eve). But that was wrong; almost everyone was confused, according to Daniel, the deacon. Because this was a leap year in the Ethiopian calendar, Christmas eve was really Saturday night, and Christmas morning on Sunday.

Happily we figured this all out by Sunday morning, when we rose before dawn. We made our way to the church where, on Saturday, a young man told us 10,000 people would be camping out. We’d scouted out a back entrance to it but were prepared to be blocked by impenetrable crowds. To our amazement, we not only slipped in but also squeezed our way to an excellent viewing spot, as generous pilgrims stepped aside to let us through.

I’d like to report that the service built to a rousing African version of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s Hallelujah chorus, but it wasn’t anything at all like that. Hundreds of priests and deacons were assembled at one end of the church courtyard, and from their midst, amplified prayers droned on and on. Finally they began to file through the church to a stairway that took them up to the edge of the pit in which the church is situated. White-robed deacons and priests and bishops eventually lined the whole perimeter and began slowly shaking their metal noisemakers and swaying in unison to a dirge-like drum beat and singing — melodies that sounded like a mixture of Gregorian chants and something you’d hear issuing from a mosque. To me, it sounded nothing at all like a ticket to heaven. But it was a Christmas to remember .

.