Last Tuesday as the afternoon sun lowered, Steve and I stood over the grave of Cecil Rhodes.

This guy, after whom the country of Zimbabwe once was named (Rhodesia), occupies one of the most dramatic final resting places I’ve ever seen.

I knew almost nothing about Rhodes before this trip, but now I can tell you: he was a ruthless, rapacious visionary. The son of an English minister, he was so sickly as a child, his family sent him as a teenager to Africa in the hope it would toughen him up. Once there, Rhodes heard about about the diamond action in Kimberly (in what’s now South Africa), moved there, and raised money (from the Rothchilds) to start buying up mine leases. He wound up essentially cornering the world diamond market and founded the De Beers Company (still a powerhouse in the diamond world.) He also resolved to build a rail line from Cape Town to Cairo through all the British possessions along the way. To do that, he needed to take the land ruled by the Ndebele king (basically today’s Zimbabwe and Zambia) and fill it with Englishmen, who would ride in comfort upon those Rhodesian rails.

Using lies, deception, and the muscle of the English crown, Rhodes succeeded so well that by the 1950s and 60s, white people held all the power in Rhodesia, and they transformed the place into something that warmed many Western hearts. At the same time, resentment among the natives built, and a vicious guerrilla war began in the 1970s. The insurgents triumphed in 1980, when the Brits relinquished their claim on the place, and the modern state of Zimbabwe was born. For most of the time since then, the black Zimbabwean elite, every bit as greedy as Rhodes, has done a pretty dreadful job of ruling. But personally, I can’t fault them any more than I blame Rhodes. He started the mess. I didn’t spit on his grave, but if anyone else had been there and done that, I wouldn’t have objected.

Nonetheless Monday through Wednesday nights, Steve and I stayed in an institution that symbolized the heart of white Rhodesian rule for 127 years, and if I’m honest I have to report: we enjoyed it.

The Club Bulawayo, both a private social club and a hotel, today is still a grand old structure paneled in expanses of dark, very shiny wood.

We were more than comfortable in our large room, spotless and equipped with comfy beds, a nice shower, and decent internet. Food served in the building’s central courtyard was good, and the handful of folks on the staff (all black) were uniformly warm and welcoming. In many ways, however, the Club is as broken as were Rhodes’ dreams of continental mastery. The 300-plus-year-old grandfather clock on the second floor still chimes, but the elevator doesn’t work (so we had to lug our bags up 62 grand steps to reach the second story). The parquet in the lobby gleams, but the corridor outside our door looked shabby.

We saw so few other guests that at times I felt like we had sneaked into and made ourself at home in a museum.

Steve and I devoted one of our two full days in Bulawayo (Zimbabwe’s second largest city) to urban amusements: visiting the national Museum of Natural History, the old railroad museum, the central public library, and more. Like our stay at the Club, these provided more tastes of lost imperial glory.

Rhodes had ordered that the streets of this city be built wide enough so a wagon pulled by 24 oxen could make a U-turn. When the ox teams disappeared, hordes of cars never replaced them, so today you can stroll around the central business district without fear of being mown down.

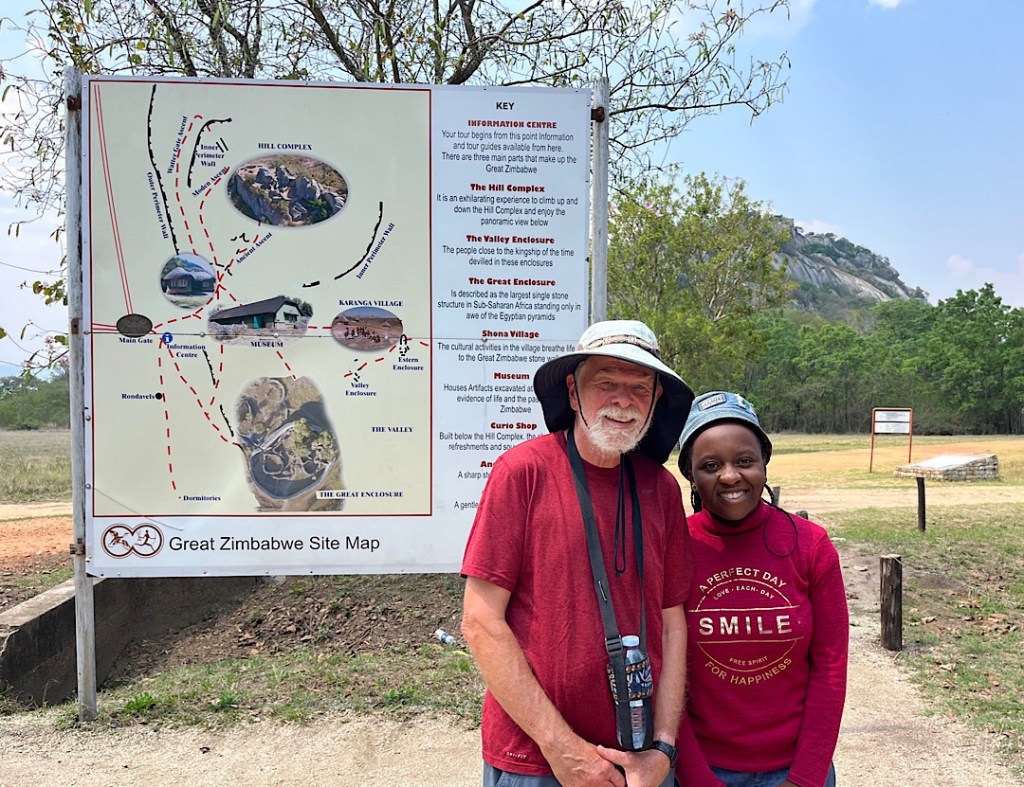

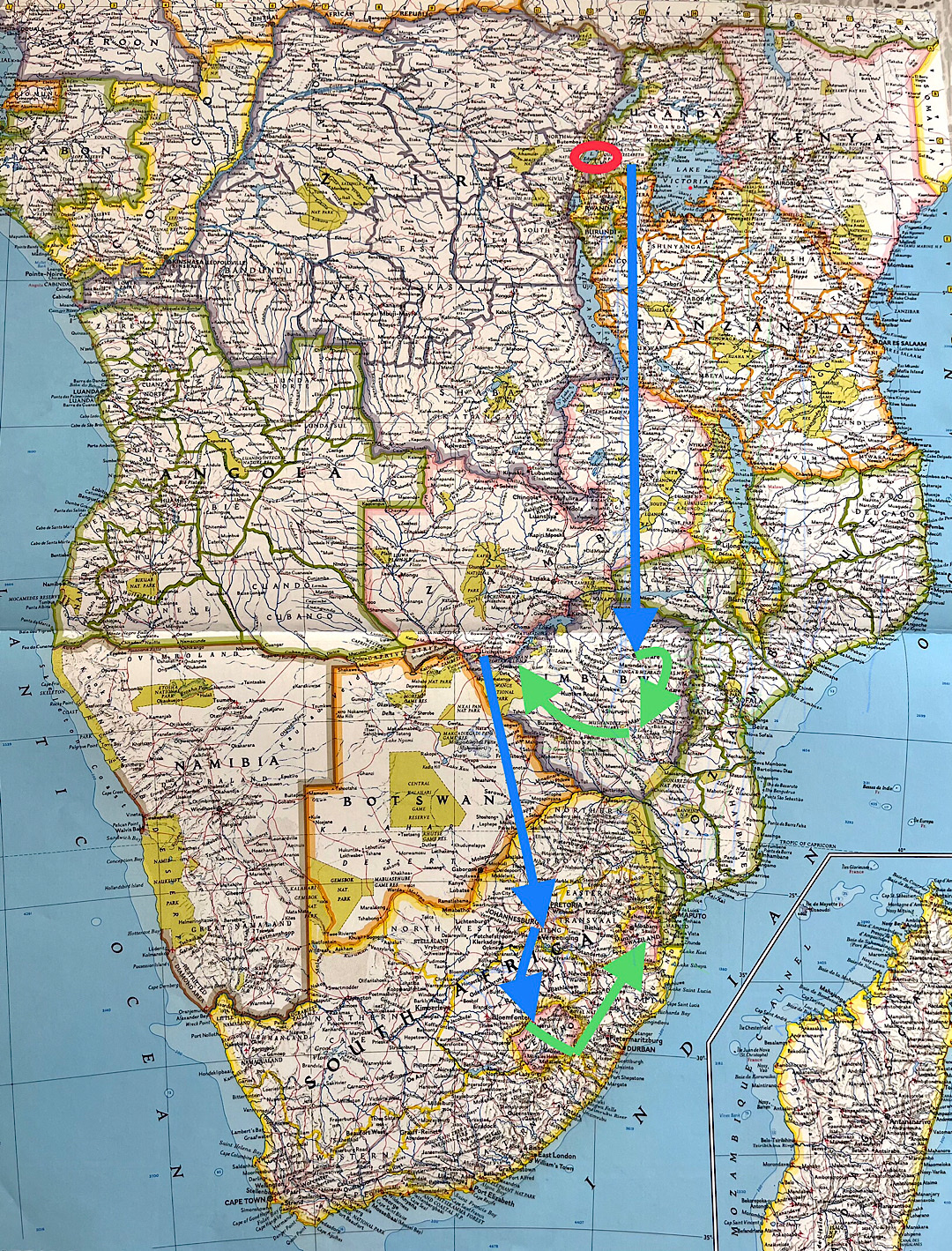

For our other full day, we had to choose between two excursions outside the city. We could have visited the Khami Ruins built about 600 years ago by people who had abandoned Great Zimbabwe after it collapsed. Steve and I had visited the Great Zimbabwe complex a few days earlier. Considered the greatest archeological site south of the Sahara, it met my (very high) expectations.

But Great Zimbabwe is basically a medieval castle, and the Khami ruins would have been more of the same (only smaller and younger.)

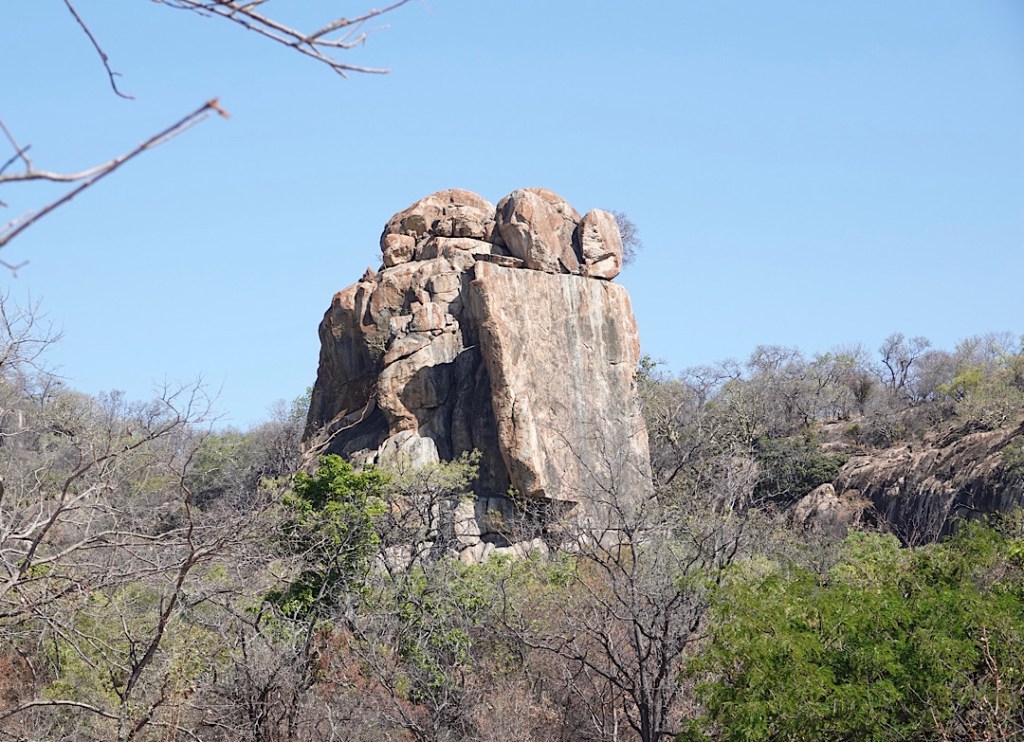

The alternative offered an experience of antiquity orders of magnitude older. So on Tuesday we drove about 30 minutes south of Bulawayo to the Matobo Hills. You could visit Matabo National Park just for the geology (or to see Rhodes’ grave, which lies within it.) Fantastic rock formations dominate the landscape, including gigantic boulders that look like they could crash down at any moment.

For us, however, the big draw was the rock paintings that line the walls of thousands of caves.

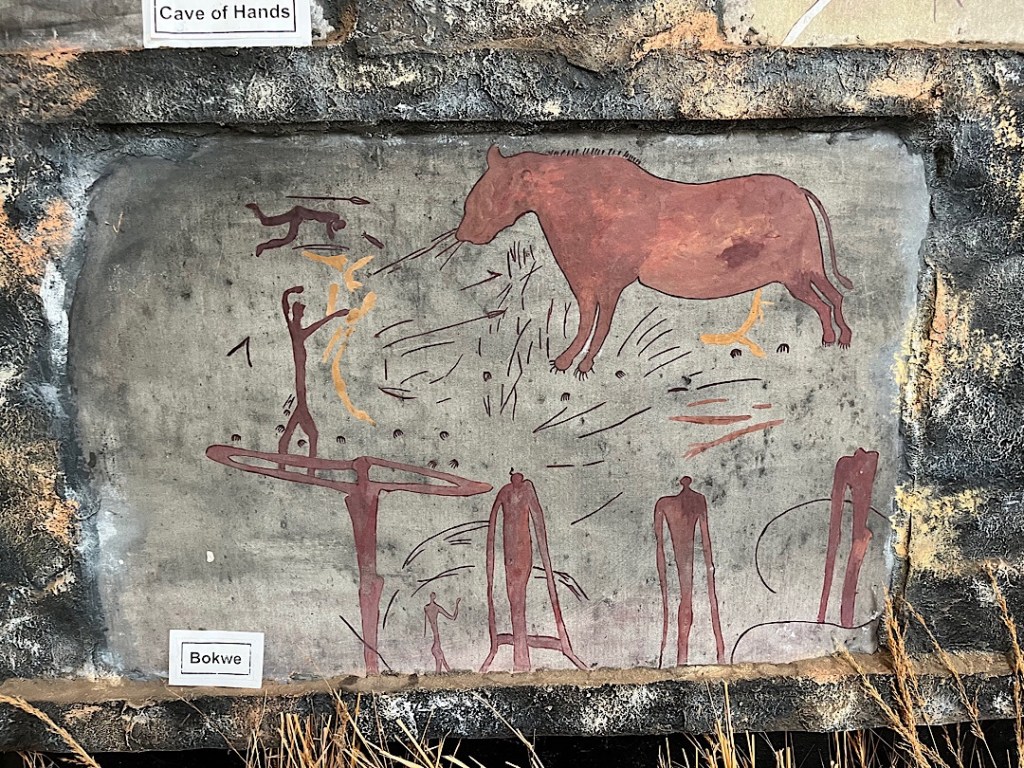

We visited two of them. The first was relatively easy to reach, down a shady dirt byway off the rocky main road. A friendly young museum attendant greeted us. His name was Knowledge. (“Yeah, seriously,” he said, aware of the humor in his parents’ choice.) He gave us a thorough, adept tour of the small but excellent museum, which filled us in on the humans who once lived in these rough shelters as long as 40,000 years ago.

Some time around 13,000 years ago, they started decorating their caves with paintings of the world around them. (Actually, even older paintings may exist; the layers underlying the cave floors have not been conclusively excavated.) The little museum contains reproductions of some of the best — far more complex than any cave paintings I’ve ever seen before.

After our tour, Knowledge led us to the Pomongwe cave a bit further down the path. The space is lovely, big enough to have housed a clan of maybe 100 folks, but sadly, the paintings were damaged around 100 years ago, when inept curators tried brightening them up with linseed oil (in preparation for a visit from some British royalty). Still, we could see how extensive and impressive they once must have been.

Knowledge urged us to visit Nswatugi Cave, less accessible but in much better condition. To get to it, we had to drive quite a bit further along dirt roads that were all but deserted. Then we had to find and follow a series of green arrows painted along the path.

Parts of the hike required scrambling up steep rocky inclines lined with brush where black mambas and puff adders lurk; other sections went up stairs and across flats. What we found at the top was worth it all.

A wonderful menagerie parades across this cave’s walls…

The images moved me in a way I find hard to articulate. Thousands of years before the Egyptians began playing in their sands, these simple hunter-gatherers stood in this space, re-creating the world that surrounded them. One thing we’ve learned on this trip is that traditionally, Africans have seen their ancestors as a link with the divine. I’ve never been able to empathize with that. I’m not particularly interested in my own great-great-grandparents and certainly can’t conceive of worshipping them.

But it strikes me now that the San people who lived in and decorated Matoba’s caves are also my ancestors. Now that I’ve seen their art, it’s not that big a stretch to imagine kneeling before them.

That’s what Steve and I will be doing Friday morning (9/15): buckling up as we take off on perhaps our most ambitious adventure.

That’s what Steve and I will be doing Friday morning (9/15): buckling up as we take off on perhaps our most ambitious adventure.

It looked like the race would take place at some course near the sea.

It looked like the race would take place at some course near the sea.

The town hall was built in 1627.

The town hall was built in 1627. That building with the red tile roof now houses the Cafe Batavia, where we ate dinner.

That building with the red tile roof now houses the Cafe Batavia, where we ate dinner. In a different latitude we might have hiked the 2-3 miles from there to central Jakarta, but the heat and humidity made that unthinkable.

In a different latitude we might have hiked the 2-3 miles from there to central Jakarta, but the heat and humidity made that unthinkable. Instead we enjoyed a tuk-tuk ride that gave us insight into Jakarta’s infamous traffic.

Instead we enjoyed a tuk-tuk ride that gave us insight into Jakarta’s infamous traffic. We abandoned our plans to climb to top when we learned it would probably take three hours to get up there, the line of locals already was that long.

We abandoned our plans to climb to top when we learned it would probably take three hours to get up there, the line of locals already was that long. The nearby national museum was less crowded. We could have spent hours, had we more time and energy but instead mostly marveled at the galleries focusing on Indonesia’s paleoanthropology. Somehow homonids who walked upright made their way from Africa to these islands a million and a half years ago. How did that happen?

The nearby national museum was less crowded. We could have spent hours, had we more time and energy but instead mostly marveled at the galleries focusing on Indonesia’s paleoanthropology. Somehow homonids who walked upright made their way from Africa to these islands a million and a half years ago. How did that happen? It was a bit before 7 pm, and people were wandering into the square and plopping down on the stones. You could feel all the energy pulsing through the place, Steve insisted. And it emanated from some of the sweetest people we’ve met anywhere.

It was a bit before 7 pm, and people were wandering into the square and plopping down on the stones. You could feel all the energy pulsing through the place, Steve insisted. And it emanated from some of the sweetest people we’ve met anywhere. Still it all looked extraordinarily convivial. Little kids tossed lighted twirling things into the air or blew bubbles. Their parents snacked on chips and drank soda. I saw a few folks getting their pictures taken with the living statues.

Still it all looked extraordinarily convivial. Little kids tossed lighted twirling things into the air or blew bubbles. Their parents snacked on chips and drank soda. I saw a few folks getting their pictures taken with the living statues.

I also saw a bunch of the wannabe photo props bored by the lack of business.

I also saw a bunch of the wannabe photo props bored by the lack of business. PS: I shot this from my window seat on the plane going into Jakarta as we were flying somewhere over Borneo. But it’s the closest we got to any big geological events. We didn’t feel so much as a small jolt. That was fine with me too.

PS: I shot this from my window seat on the plane going into Jakarta as we were flying somewhere over Borneo. But it’s the closest we got to any big geological events. We didn’t feel so much as a small jolt. That was fine with me too. The news was discouraging when we landed on Rinca Island Tuesday afternoon. No one had spotted any Komodo dragons that entire day — nor the day before. I tried to resign myself to the same fate. When you seek rare animals in the wild, it’s not like buying a movie ticket. You’re not guaranteed a show. But we lucked out.

The news was discouraging when we landed on Rinca Island Tuesday afternoon. No one had spotted any Komodo dragons that entire day — nor the day before. I tried to resign myself to the same fate. When you seek rare animals in the wild, it’s not like buying a movie ticket. You’re not guaranteed a show. But we lucked out.

Another score! The ranger asked for Steve’s phone and recorded the temporary occupant: a male whose big belly testified to recent consumption of a meaty feast. Now he was digesting in the cool comfort of the man-made shelter.

Another score! The ranger asked for Steve’s phone and recorded the temporary occupant: a male whose big belly testified to recent consumption of a meaty feast. Now he was digesting in the cool comfort of the man-made shelter.

This was breakfast the second morning.

This was breakfast the second morning. The view from near the top, taking in three different-colored beaches (black, white, and pink) is so famous it’s on Indonesia’s 50,000-rupiah bank note. Indonesian tour groups pressed for time will often choose to visit it and skip the Komodo dragons, according to Robert.

The view from near the top, taking in three different-colored beaches (black, white, and pink) is so famous it’s on Indonesia’s 50,000-rupiah bank note. Indonesian tour groups pressed for time will often choose to visit it and skip the Komodo dragons, according to Robert.

This time our park ranger, Dula, took my iPhone and shot the wonderful video footage I will try to incorporate here. I hope it’s viewable on the blog; part terrifying, part comic, it’s documentary evidence of one of the most unforgettable strolls of my life.

This time our park ranger, Dula, took my iPhone and shot the wonderful video footage I will try to incorporate here. I hope it’s viewable on the blog; part terrifying, part comic, it’s documentary evidence of one of the most unforgettable strolls of my life. We didn’t succeed at seeing all of it. The wind blew hard for a few hours on our final morning, whipping up white caps that drove the local manta rays and sea turtles to deeper water. But we did manage to snorkel three times in calm water, and each outing delighted me. The sea was clear and warm, and I felt as close as I will ever get to flight, gliding effortlessly over the landscape of coral and anemones and rocks, in the company of neon-colored fish, many dressed up in astonishing patterns. At times we sailed by rivers of fish; into clouds of them. Once I started to laugh out loud at the concentrated beauty but was quickly reminded that’s not a great idea when you’re breathing through a snorkel.

We didn’t succeed at seeing all of it. The wind blew hard for a few hours on our final morning, whipping up white caps that drove the local manta rays and sea turtles to deeper water. But we did manage to snorkel three times in calm water, and each outing delighted me. The sea was clear and warm, and I felt as close as I will ever get to flight, gliding effortlessly over the landscape of coral and anemones and rocks, in the company of neon-colored fish, many dressed up in astonishing patterns. At times we sailed by rivers of fish; into clouds of them. Once I started to laugh out loud at the concentrated beauty but was quickly reminded that’s not a great idea when you’re breathing through a snorkel. We watched the molten tangerine sliver of sun shrink to a dot and disappear and the color begins to drain from the sky. Several long moments passed, but enough of a glow still remained that I could make out the strange thing that began to occur — a stream of tiny black objects rising out of the mangroves like cinders flowing up from a campfire and dispersing.

We watched the molten tangerine sliver of sun shrink to a dot and disappear and the color begins to drain from the sky. Several long moments passed, but enough of a glow still remained that I could make out the strange thing that began to occur — a stream of tiny black objects rising out of the mangroves like cinders flowing up from a campfire and dispersing. The stream thickened and grew; that’s when I cried out. These were fruit bats, a vast horde of them, ranging out by the millions to hunt insects in the night.

The stream thickened and grew; that’s when I cried out. These were fruit bats, a vast horde of them, ranging out by the millions to hunt insects in the night.