First things first: Trump’s changing of the name from Denali to Mt. McKinley. I can report with confidence you’d never know it in the national park. The park entrance, the visitor’s center, and countless other signs all still say Denali, deriving from the native (Athabaskan) word for “high one.”

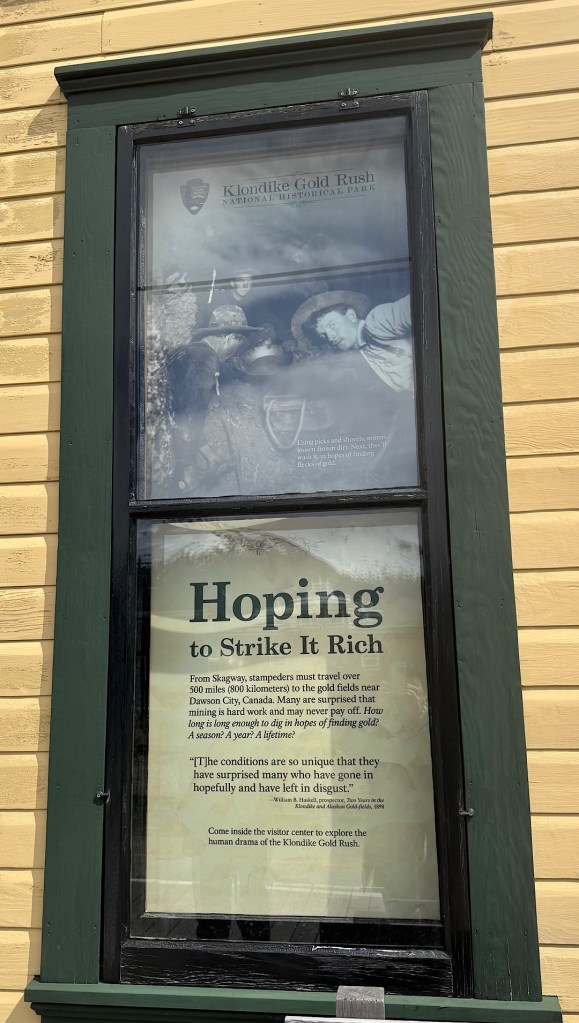

The mountain got dubbed “Mt. McKinley” by an East Coast gold-hunter in 1896, but according to my Fodor’s, the vast majority of Alaskans always continued to call it by its original name (which Barack Obama made official in 2015.) I finally found the name Mt. McKinley in one place: the giant relief map in the visitor’s center.

Besides my fruitless search for any sign of the name change, Steve and I spent a big chunk of our time in the national park on safari, scanning for big game. Beavers aren’t among the very biggest, but they’ve made a mark on the landscape. We hiked for three miles near the visitor’s center Sunday morning, and on Horseshoe Lake the rodents’ handiwork was dramatic.

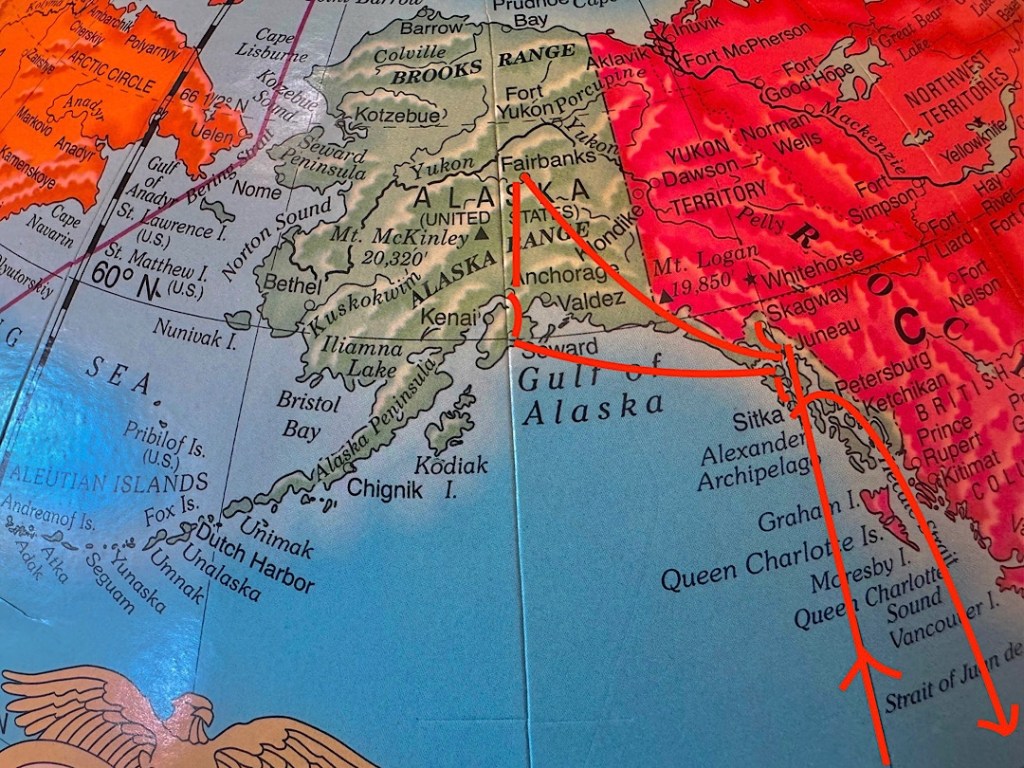

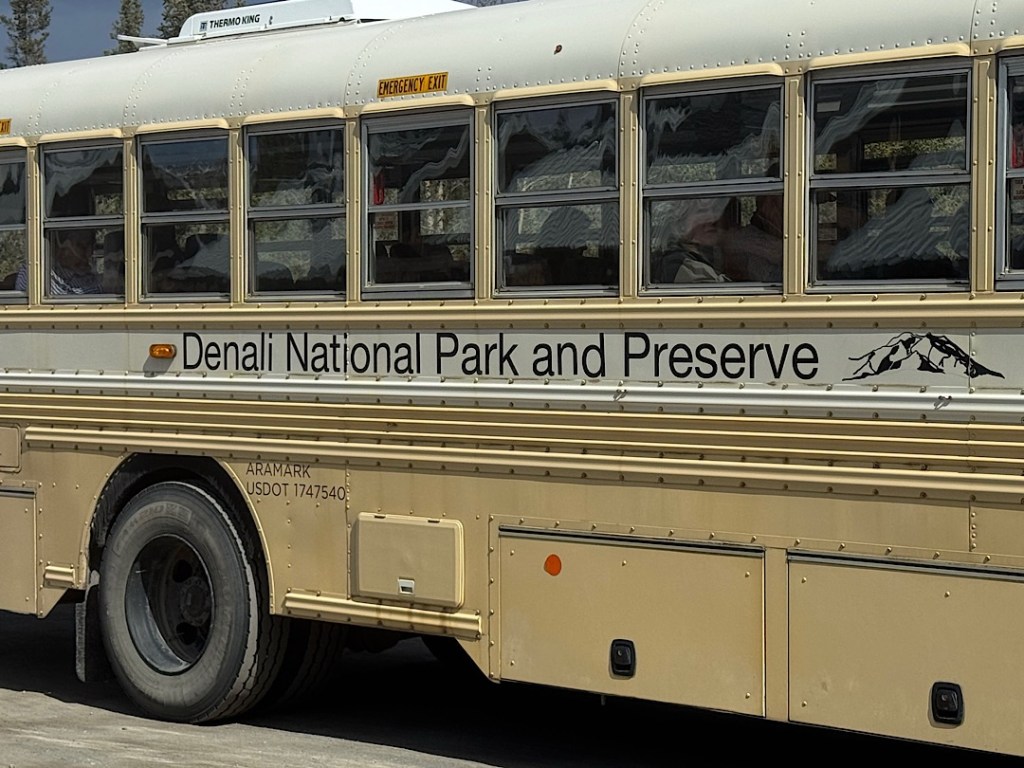

That afternoon we took a bus tour. I can’t say it showed us the park because this park is the size of Massachusetts. Only one road runs through it, actually half a road since 2021 when a worsening landslide section made the road impassible about 43 miles in. Access beyond that point has been blocked ever since, though a bridge to span the missing bit is nearing completion. It took our bus driver about 6 hours to take us close to the avalanche site and back.

We drove through two kinds of terrain that neither Steve nor I had ever before laid eyes on, even though both rank among the largest biomes on earth. Taiga is a type of forest that has long cold winters and short mild summers. Tundra is similar but treeless. Vast areas of Canada, Russia, Northern Europe, and Alaska consist of the two.

Now that I’ve seen it, I have to say taiga (for me) ranks among the sorriest woods on the planet. Only 5 species of trees grow below the tree line, the vast majority white spruce. They look scrawny and sad and tipsy. (When the ground thaws, the trees tend to lean.)

Some of the 5-foot-tall specimens are hundreds of years old, our guide told us. Only a few kinds of shrubs grow beneath the trees. It’s a half-planet away from the lush life-choked equatorial jungles I’ve seen and loved.

From the bus, the tundra looked equally moribund, though that was illusory, In a month or two, we heard, the thin, thawed topsoil will be carpeted with hundreds of species of tiny wildflowers, woody plants, berries, mosses, lichens and fungi. Still, even in the best of times, Denali’s plant life isn’t enough to sustain many animals, with a few striking exceptions. The Big Five in the park consist of:

Wolves — They blend in with the landscape and run in packs that cover large areas so they’re notoriously hard to spot. Sunday afternoon we didn’t get lucky.

Grizzly (brown) bears — Next to a grassy hillside, someone noticed a tiny dark form up near the ridge line. For a few excited minutes, our driver/guide thought it might be a bear, but then it flew away. Score for the day: one golden eagle; zero bears.

Dall sheep — They’re striking animals up close, but they usually hang out on steep, high slopes. We spotted several, but I have to confess, the teensy white specks looked nothing like the stuffed Dall sheep in the visitor’s center.

Caribou — We had a great day finding these North American reindeer.

Moose — My moose score remained pathetic for most of the day, then after our bus had dropped off most of the passengers at the visitor’s center and were being ferried back to our hotel, we came upon a local police car stopped with its lights flashing. Our driver hit the brakes. Just off the road in front of us, a female moose was foraging. She glanced up but kept on munching. I was thrilled.

I haven’t mentioned the biggest score for anyone visiting Denali National Park: seeing the famous mountain. I knew Denali was the tallest mountain in North America, topping out at 20,310 feet. What I did not know is that a good case can be made it’s actually the biggest mountain on earth if you’re considering the vertical rise — the distance between the base and the peak. Mt. Everest is 29,035 feet, but its base lies on a 17,000-foot-high plateau. So its vertical rise is about 12,000 feet. Denali’s base is only about 2000 feet above sea level, and it looms 18,000 more feet above that. That’s actually more impressive to gaze upon.

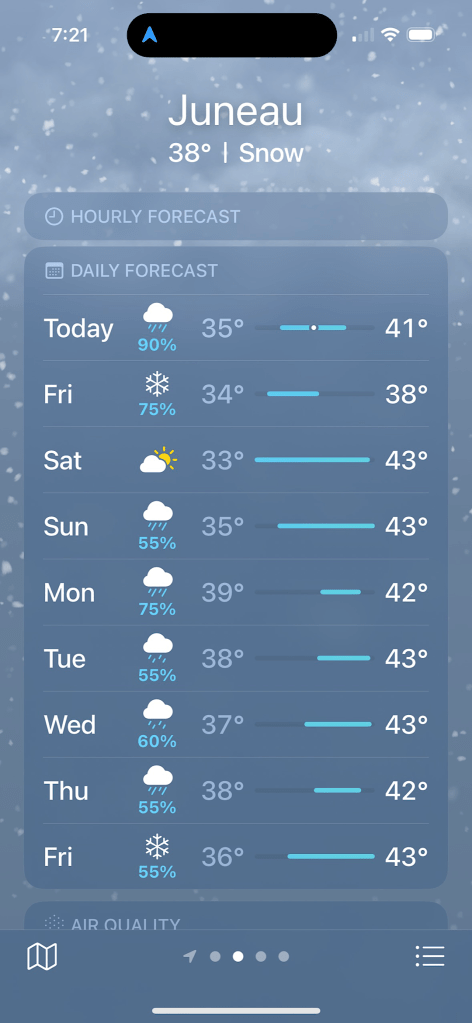

IF you can see it! That’s the rub. The “High One” is so high rangers say it creates its own weather system, usually obscuring the views with clouds and fog. When Steve and I went out Saturday afternoon to a point on the road where Denali should have been visible, all we saw was what 70 to 75% of the park’s visitors see: impenetrable gray.

The next day began clear and sunny, but at the start of our bus ride shortly after noon, the same mysterious clouds obscured the mountain. To my delight, however, they soon began to clear.

We left the park the next afternoon on the Alaska Railways train to Anchorage, and the mountain’s fantastic visibility improved.

Not only that, but we saw several more moose running in nearby meadows. I wasn’t quick enough to photograph them, so you have to take my word for it.