I’m publishing this post from my desk in San Diego, where I’m immersed in Re-Entry. I’ve been tempted to blow off writing anything more about Japan. Our time in Osaka was gratifying and fun, but maybe not so interesting to read about. We made a quick day trip to Nara, the ancient Japanese capital and a magnet for visitors who come to feed special crackers to the vast numbers of semi-wild deer.

Nara Park contains some fabulous creations, including Tōdaiji Temple, where the largest wooden building ever constructed…

…shelters one of the world’s largest statues of the Buddha.

Steve and I also briefly strolled the grounds of the mighty Osaka Castle. But mostly we concentrated on food in this city known as “the grocery store of Japan.” One morning we spent a couple hours roaming the area around Dotonbori Street, a vortex for delicious street food and outrageous building decoration.

Everywhere we looked, we saw people lined up in the street; we despaired of getting a taste of any of it. But on a quiet byway we finally scored some marvelous takoyaki.

On that walk I also spotted a homeless person — the first I’ve ever seen in Japan.

That evening we joined an “Osaka food tour” that introduced us to more than a dozen local specialties.

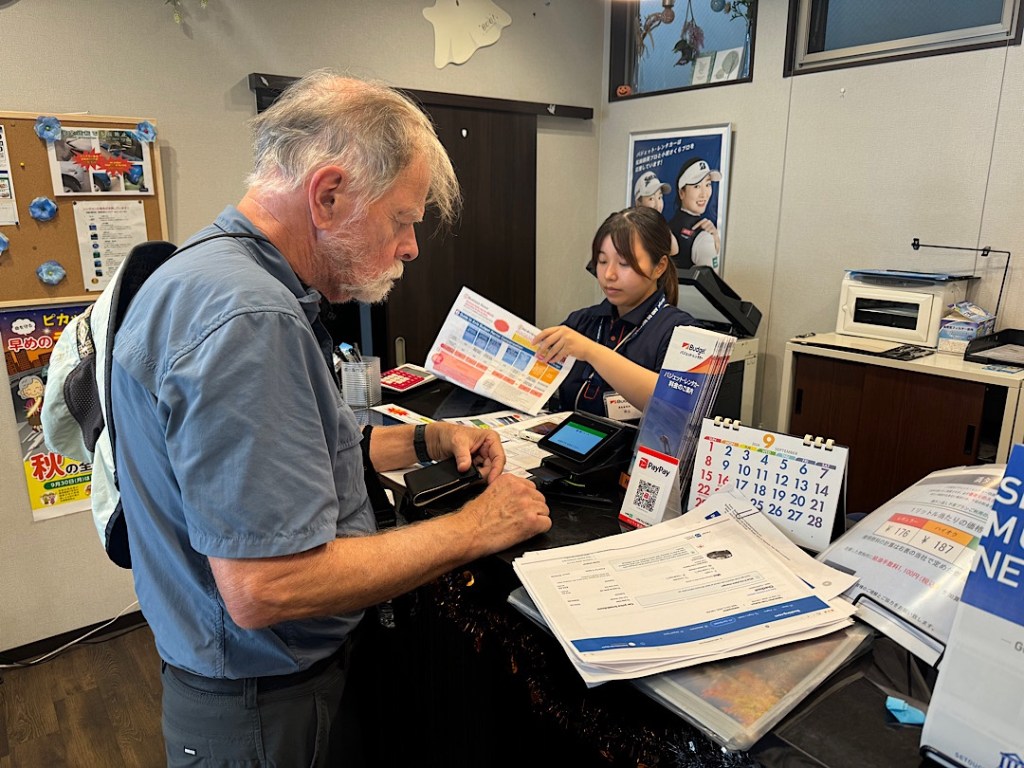

I’ve been so bowled over by and enthusiastic about our experiences on this trip, I’m a little worried I may sound undiscriminating. So I decided I should chronicle at least one thing at which we found the Japanese to be mediocre: They don’t explain themselves well to foreigners.

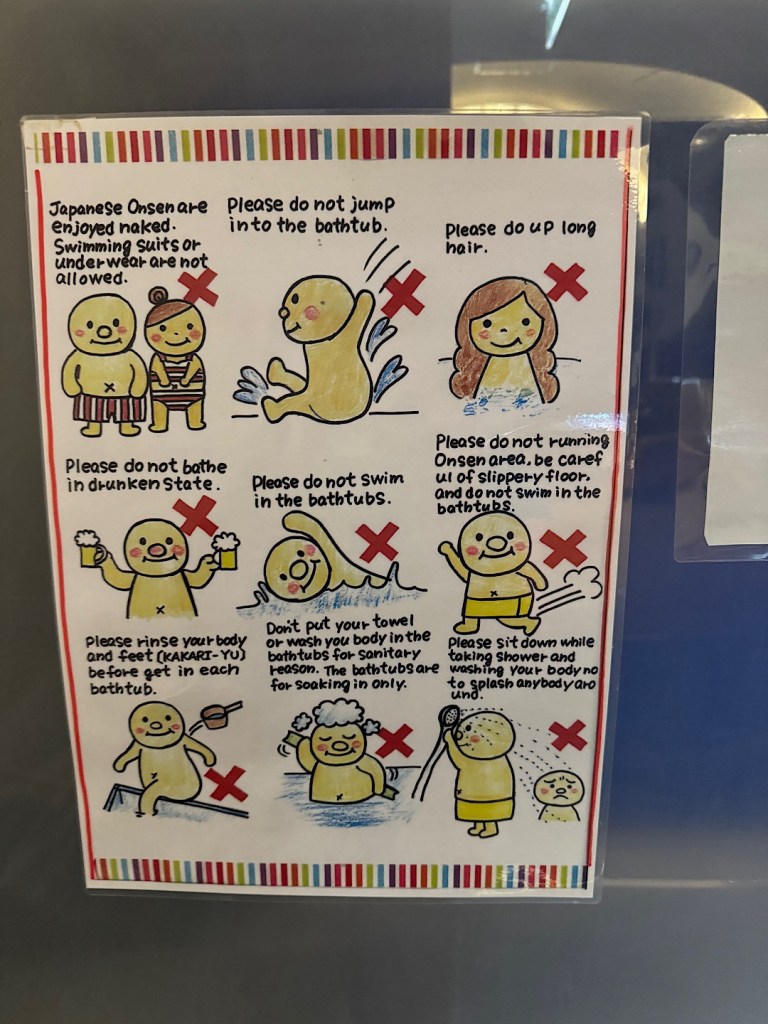

Over and over, even in famous, important sites, we found a shocking dearth of signs or placards or other educational material in English (or any language other than Japanese.) To some extent, we could overcome this by using Google’s Translate app or Google Lens. We’ve never used either much before, but today they’re game-changers in a country where you can’t read. They liberated us to waltz into restaurants without worrying if an English menu would be available (as often as not, it wouldn’t be.) They helped us figure out air-conditioning controls and all manner of street warnings and how to work a coin-op washer/dryer.

But in situations where there’s a ton of information being conveyed, for example at the Kyoto Railway Museum, the language apps don’t work that well. They take time to do their translating, and they require good Internet. (Our T-Mobile service was often tooth-grindingly slow.)

Our experience at the railway museum was particularly disappointing. The facility is enormous, and everything in it is bright and shiny and beautiful.

Steve and I went to the railway museum because our respect for Japanese railway technology knows no bounds. The country’s urban train systems are a wonder of the world — a stunning profusion of companies and services, with most trains arriving on time to the minute. For longer trips, the Shinkansen bullet trains have changed the world since the first one went zooming down the rails (50 years ago this month.)

We had hoped to learn the bullet trains’ story — to hear about the initial vision for high-speed rail; get insight into what the biggest challenges were and how they were solved. But almost none of the museum’s relevant signage was in English, and even the Japanese-language information seemed sketchy. I’ll probably forget our whole visit there within weeks.

I can’t say that about the actual train that carried us from Kyoto to Osaka last Sunday. It wasn’t a bullet train. I don’t even remember how I learned about it. (Maybe a one-line mention in some guide book I consulted?) The Kyo-train GARAKU, as it’s called, only operates on weekends and holidays. The one we caught (the first of four making the round-trip that day) wasn’t mobbed with tourists. Many of our fellow passengers were Japanese. We didn’t have to buy any special ticket. We just used our marvelous “IC” cards (which worked on every bus, train, and metro line we took throughout the country, except for the Shinkansens.)

The 45-minute one-way trip from Kyoto to Osaka cost 410 yen, just under $2.75 per person. It was the most beautiful train I’ve traveled on anywhere.

Why did the Hankyu Railway (a private company) build this thing? Why do they charge so little for it? Why go to so much expense and effort to carry some passengers between Kyoto and Osaka (something Hankyu does routinely every day)?

As usual, there were no signs, no brochures answering any of my questions. We just had to enjoy it, in wonder.