Considering what a small (and little-visited) country Ecuador is, I wouldn’t have been surprised to find it pleasant but unmemorable (apart from the Galapagos Islands, which are unique.)

Parts of our short stay were like that. But four experiences electrified me.

Watching the changing of the government-palace guard in Quito

I’ve seen the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, but the ceremony at Quito’s government palace (the Ecuadorian equivalent of the White House) makes the British version seem dull. Commentators trace its origins back more than 200 years, to shortly after Ecuador won its independence from Spain. In recent years, it has taken place every Monday, though the start time has shifted around a bit. We’d heard it was worth seeing. That’s an understatement.

government palace (the Ecuadorian equivalent of the White House) makes the British version seem dull. Commentators trace its origins back more than 200 years, to shortly after Ecuador won its independence from Spain. In recent years, it has taken place every Monday, though the start time has shifted around a bit. We’d heard it was worth seeing. That’s an understatement.

We got to Plaza Grande, the city’s most iconic square, shortly before 8:30 am a week ago Monday. The presence of cops and a few brightly dressed palace guards milling around on the second-story balcony made us think something was afoot, but the action coalesced gradually. Guards astride flashy horses appeared, bearing flags. More guards with lances positioned themselves near the rooftop. Precisely at 9:00 the strains of stately, grandiose music became discernible, first faintly, then louder and louder, as almost two dozen trumpet- and clarinet- and trombone- and tuba- and bass-drum- and other instrument-playing guards emerged from the inner recesses of the palace. It was music with the power to raise the hairs on the back of necks; music that made me wish I could leave my viewing spot and march along.

Precisely at 9:00 the strains of stately, grandiose music became discernible, first faintly, then louder and louder, as almost two dozen trumpet- and clarinet- and trombone- and tuba- and bass-drum- and other instrument-playing guards emerged from the inner recesses of the palace. It was music with the power to raise the hairs on the back of necks; music that made me wish I could leave my viewing spot and march along.

What followed went on for close to a half an hour, and it was too complicated to describe in detail: parading horses and solemn proclamations over a loudspeaker and marching lance-bearers and more and more of the thrilling music. (One missing element was the Ecuadorian president’s appearance on the uppermost balcony, another long-time part of the show. Whether he was just on vacation or worried about his plummeting popularity, I can’t tell you.)

What followed went on for close to a half an hour, and it was too complicated to describe in detail: parading horses and solemn proclamations over a loudspeaker and marching lance-bearers and more and more of the thrilling music. (One missing element was the Ecuadorian president’s appearance on the uppermost balcony, another long-time part of the show. Whether he was just on vacation or worried about his plummeting popularity, I can’t tell you.)

Still it was most entertaining, and I couldn’t help chuckling at this small, not-very-prosperous country putting on such a flamboyant display of stately pomp. (I also thought: better them than us.)

Getting caught in the demonstration We happened upon our first Ecuadorian political demonstration, a small group protesting in front of the presidential palace, during our free walking tour of the city. “We Ecuadorians love demonstrations,” our guide declared. “You’re going to see a lot of them.” She got that right. During our four days in Quito, we witnessed at least three or four public protests, and I got a text from the US State Department warning that several big ones were expected on one of the days we were there. We should avoid them, the message ordered, but this wasn’t possible during our hop-off, hop-on bus tour of the city’s major sights.

We happened upon our first Ecuadorian political demonstration, a small group protesting in front of the presidential palace, during our free walking tour of the city. “We Ecuadorians love demonstrations,” our guide declared. “You’re going to see a lot of them.” She got that right. During our four days in Quito, we witnessed at least three or four public protests, and I got a text from the US State Department warning that several big ones were expected on one of the days we were there. We should avoid them, the message ordered, but this wasn’t possible during our hop-off, hop-on bus tour of the city’s major sights.

The bus was a double-decker, and Steve and I were sitting on the open second level. From blocks away, we could see a large crowd down the street. We assumed the bus would detour around it, but instead, we headed straight for the protesters and the police and their snarling canines.

Within short order, the mob surrounded the bus. People chanted. Vuvuzelas blared. Despite the signs, it was unclear what was angering the protesters (though cutbacks to healthcare subsidies seemed to be involved.) I suspected the State Department wonk who sent out the text message wouldn’t have approved of our being in the thick of it. But the crowd seemed more high-spirited than menacing, and the cops looked chill.

I suspected the State Department wonk who sent out the text message wouldn’t have approved of our being in the thick of it. But the crowd seemed more high-spirited than menacing, and the cops looked chill.

After a few minutes, the mob parted and the bus rolled along its way. None of our other stops were anywhere near as thrilling.

Meeting the man behind the hacienda

We spent one night in the Ecuadorian countryside, in what Lonely Planet described as a “fairy-tale 17th-century hacienda.” Our friends had stayed there for a night, and we could see why they loved it. The gardens were exquisite.

And the interiors felt like a museum.

The spine-tingling moment for us came when a distinguished looking gentlemen approached us while we were dining in the grand salon (above). He introduced himself as the owner, Nicholas Millhouse, and over the course of the next hour or so, he shared a small part of the saga that began when he bought the hacienda in 1990 and undertook the gigantic art project of restoring it from near ruin to its current glory.

An Englishman who spent his career teaching at a tony private school in Manhattan, he had early developed a passion for South America. For decades, he roamed the continent, collecting exquisite textiles and other works of art.

The next morning, we spent more time in his company, enjoying his sense of humor…

…and learning a little about indigenous art and beliefs.

Millhouse also commissioned this cross, which incorporates important indigenous elements, such as substituting a mirror for the figure of the crucified Christ.

Millhouse still spends most of the year in Manhattan, so it was pure chance that we happened to be at the hacienda when he was in residence there. That blew our minds.

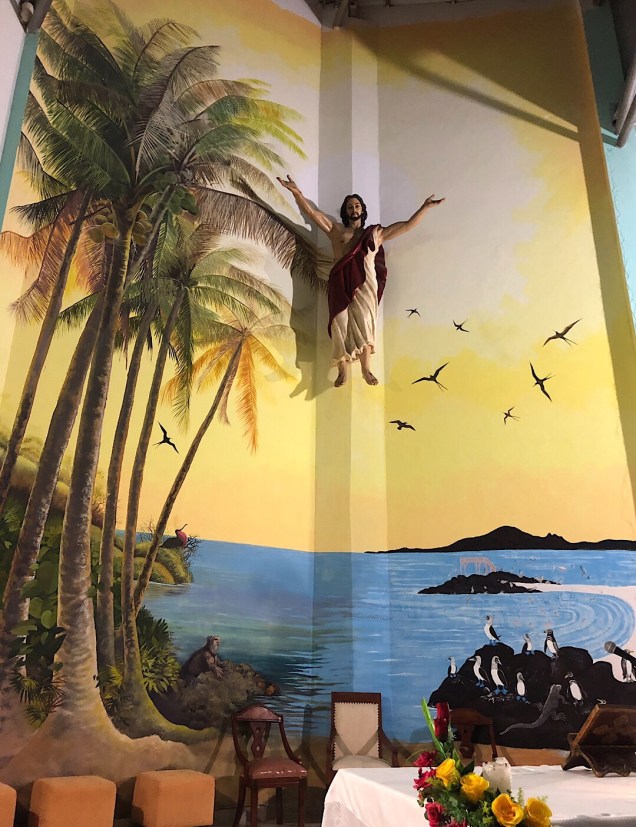

Walking into La Compañia

I’ve seen a lot of churches in my time, but few, if any, have struck me as being as beautiful as the Jesuit one in the heart of Ecuador’s capital. Somehow all the gold makes the place feel cheery and inviting, rather than garish.

Supposedly, the Jesuits wanted the worshipping natives to feel like they had died and gone to heaven. Surely they must have succeeded.

Taking in the heartbreaking natural beauty

There’s no single moment I was poleaxed by Ecuador’s physical beauty. Instead it bowled me over and over: upon landing in Quito. Or horseback riding at the hacienda. Or drinking in the viewpoint, reached via cable car, near one of the city’s volcanos.

Or drinking in the viewpoint, reached via cable car, near one of the city’s volcanos.

It’s one of the most beautiful natural landscapes I’ve encountered, and one of the reasons Ecuador should rank among the richest countries in the world, a South American Switzerland. The land also is fertile, blessed with so many microclimates almost everything can be grown here. Ecuador has more oil than anywhere on the continent except for Venezuela and Brazil. It contains vast gold reserves, not to mention the natural wonder of the Galapagos.

Instead, Ecuadorians struggle with strangling regulation, corrupt politicians, and almost-constant turmoil. (They’ve had 20 Constitutions since independence; 17 presidents between 1930 and 1940). That’s the heartbreaking part.

Will all those demonstrations lead to a better future for folks like her? Will some other force? If the creativity and energy latent in the Ecuadoreans could be unloosed, that would be truly electrifying.

Others created striking objects using more traditional hand looms. Why not spend a little time in Ecuador on our way home from the eclipse, and buy a rug from one of those guys?

Others created striking objects using more traditional hand looms. Why not spend a little time in Ecuador on our way home from the eclipse, and buy a rug from one of those guys? …and walked to the workshop of Don José Cotacachi.

…and walked to the workshop of Don José Cotacachi.

But Steve and I were struck by a problem with using any of it to cover our floor. The largest pieces were less than four by five feet, smaller than what we were seeking. Furthermore, they weren’t very thick but rather more suitable for hanging on a wall or covering a bed. They’d be a bitch to vacuum, and we could all too readily imagine our dogs turning them into a rumpled pile of cloth.

But Steve and I were struck by a problem with using any of it to cover our floor. The largest pieces were less than four by five feet, smaller than what we were seeking. Furthermore, they weren’t very thick but rather more suitable for hanging on a wall or covering a bed. They’d be a bitch to vacuum, and we could all too readily imagine our dogs turning them into a rumpled pile of cloth.

I also had five electrifying Ecuadorian experiences. I hope to share them in one more final, brief post.

I also had five electrifying Ecuadorian experiences. I hope to share them in one more final, brief post. I was long baffled that Steve was never eager to visit the Galápagos. Both natural history and evolutionary biology have always fascinated him. There’s a lot of both in the island chain 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador. The place intrigued me, but the price of visiting always discouraged both of us. No tourism of any sort existed before the mid-1960s, and then for many years, the only way to see the place was to take the almost two-hour flight out, then board a ship that would likely cost at least $2500 per person for a basic five-day cruise and many thousands more for a longer or posher experience. For that kind of money, we typically cover a lot of ground.

I was long baffled that Steve was never eager to visit the Galápagos. Both natural history and evolutionary biology have always fascinated him. There’s a lot of both in the island chain 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador. The place intrigued me, but the price of visiting always discouraged both of us. No tourism of any sort existed before the mid-1960s, and then for many years, the only way to see the place was to take the almost two-hour flight out, then board a ship that would likely cost at least $2500 per person for a basic five-day cruise and many thousands more for a longer or posher experience. For that kind of money, we typically cover a lot of ground.

In the end, our stay (including the $180 required per person in permits) cost us about $800 each, rather than the $2,500-$5000 per person the cruising probably would have. And we learned a lot.

In the end, our stay (including the $180 required per person in permits) cost us about $800 each, rather than the $2,500-$5000 per person the cruising probably would have. And we learned a lot.

In the Mendoza Airport yesterday, I heard a woman talking about someone she knew who had seen 20 total solar eclipses. I know such people exist; they more or less dedicate their lives to traveling the world to wherever it is the sun will next be totally blocked out by the moon. (This happens only once every year or two.) When I saw my first total solar eclipse in 1999, it affected me so powerfully I vowed to see as many as I could for the rest of my lifetime. I’ve since decided this requires a level of nuttiness that, nutty as I may be, I lack. Seeing only three has taught me how many decisions you have to make, any one of which can turn out to be disastrous.

In the Mendoza Airport yesterday, I heard a woman talking about someone she knew who had seen 20 total solar eclipses. I know such people exist; they more or less dedicate their lives to traveling the world to wherever it is the sun will next be totally blocked out by the moon. (This happens only once every year or two.) When I saw my first total solar eclipse in 1999, it affected me so powerfully I vowed to see as many as I could for the rest of my lifetime. I’ve since decided this requires a level of nuttiness that, nutty as I may be, I lack. Seeing only three has taught me how many decisions you have to make, any one of which can turn out to be disastrous. San Juan would be on the far southern edge of the eclipse arc, we knew, but the sun would only be totally covered there for about 30 seconds. In contrast, if we drove north to the center of the path, the eclipse would last close to two and a half minutes. Totality is so spectacular, you want it to last for as long as possible. But what I learned as I researched all this (months ago) is that there aren’t a lot of options for getting around in this part of western Argentina. Professional astronomy sites said the towns of Rodeo and Bellavista were likely to be best, but I had trouble finding them on any map (even Google’s). The only roads leading to them from San Juan crossed a mountain spur, and I could find no clue to what their condition would be.

San Juan would be on the far southern edge of the eclipse arc, we knew, but the sun would only be totally covered there for about 30 seconds. In contrast, if we drove north to the center of the path, the eclipse would last close to two and a half minutes. Totality is so spectacular, you want it to last for as long as possible. But what I learned as I researched all this (months ago) is that there aren’t a lot of options for getting around in this part of western Argentina. Professional astronomy sites said the towns of Rodeo and Bellavista were likely to be best, but I had trouble finding them on any map (even Google’s). The only roads leading to them from San Juan crossed a mountain spur, and I could find no clue to what their condition would be.

Along the road, we spotted the first of a series of signs announcing a “Punto de Observacion” (eclipse observation point) ahead, which in itself reassured me. (If there was an official observation point, clearly we wouldn’t be alone.)

Along the road, we spotted the first of a series of signs announcing a “Punto de Observacion” (eclipse observation point) ahead, which in itself reassured me. (If there was an official observation point, clearly we wouldn’t be alone.) It also dispelled another worry: If the road led us to a point too close to the Andean foothills to the west of us, the sun might actually be behind them by 5:39 pm (when totality would start). But if locals had picked an observation point and then created and posted glossy signs leading to it, surely they must have chosen a site where the mountains wouldn’t block our view.

It also dispelled another worry: If the road led us to a point too close to the Andean foothills to the west of us, the sun might actually be behind them by 5:39 pm (when totality would start). But if locals had picked an observation point and then created and posted glossy signs leading to it, surely they must have chosen a site where the mountains wouldn’t block our view. .

. We had no folding chairs like most of the local folks, but Michael scouted out a spot behind a half-built stone building that sheltered us from the wind.

We had no folding chairs like most of the local folks, but Michael scouted out a spot behind a half-built stone building that sheltered us from the wind. Climbing up on its roof offered excellent views both of the sinking sun…

Climbing up on its roof offered excellent views both of the sinking sun… and the surrounding crowd.

and the surrounding crowd. We anchored our sign with a cinder block and uncorked one of the bottles, poured ourselves a glass, and settled in to wait.

We anchored our sign with a cinder block and uncorked one of the bottles, poured ourselves a glass, and settled in to wait.